Some movies are clichéd. Some movies are unengaging. But some movies go beyond the offense of boring the audience, making them feel repulsed instead. They demean the moviegoers and reinforce a racist worldview, all while pretending to be harmless and profound. “Lost in Translation,” Sofia Coppola’s widely praised 2003 film featuring Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson, falls under that heinous category of motion pictures.

“Lost in Translation” asks viewers to characterize Japan as strange and uncomfortable to relate to the loneliness of the protagonists. To accomplish the emotional objectives of the movie, audience members are forced to adopt the white gaze and look down on another race. Further, “Lost in Translation” reinforces negative stereotypes of Asians, contributing to systemic racism and the false notion often perpetuated by movies that only white people have complex lives and thoughts.

Many audience members, like myself, don’t want to participate in that belittling of Asian culture. It’s degrading and crude. After 102 infuriating minutes, legendary film critic Roger Ebert’s immortal words from his review of the movie “North” appeared in my head: “I hated this movie… Hated every simpering stupid vacant audience-insulting moment of it.”

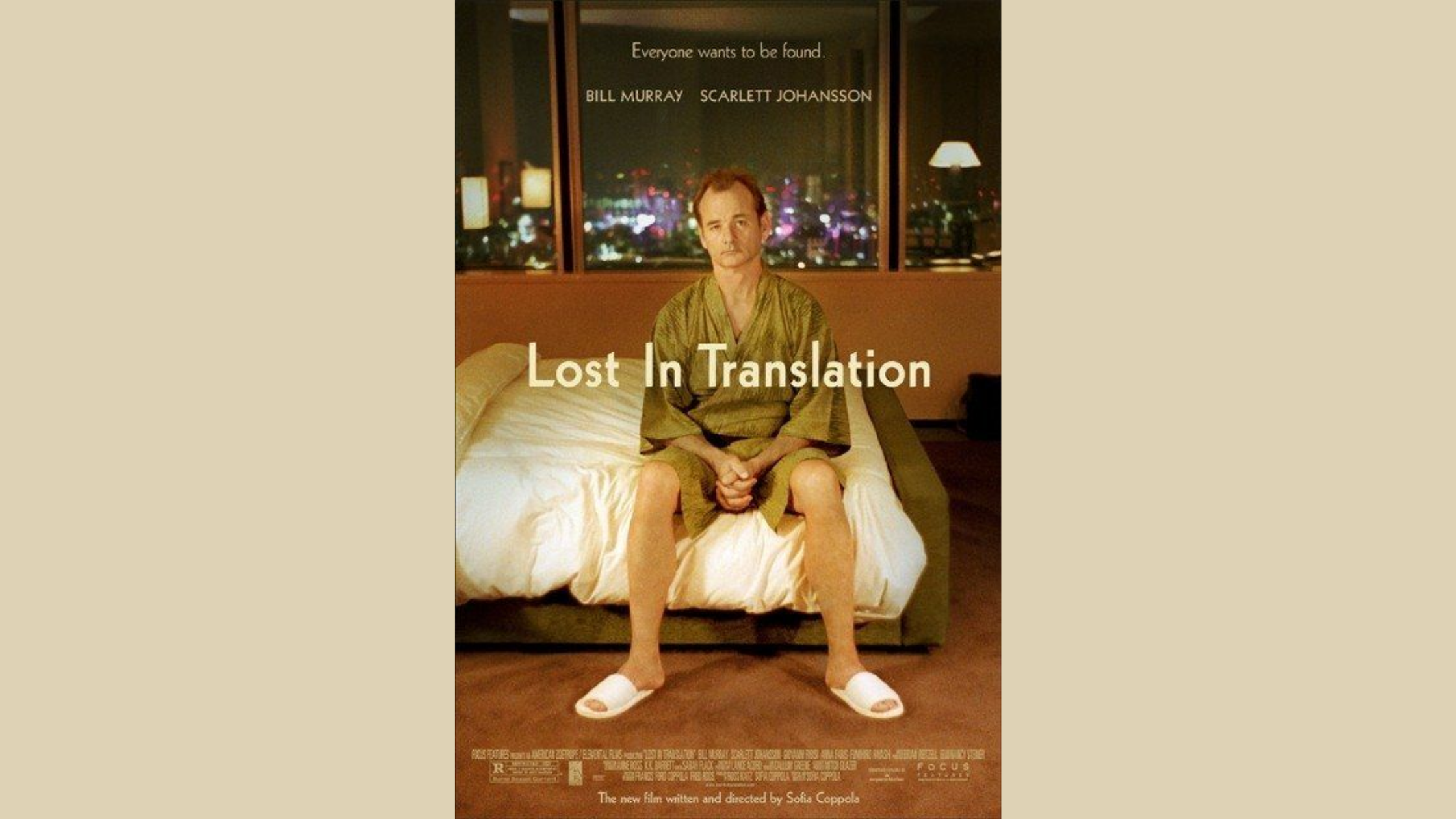

What plot could a movie possibly have to be deemed so abhorrent? The story centers around Bob Harris (Bill Murray), an American actor past his prime, and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson), the wife of a successful photographer. They both travel to Japan against their will –– Harris is shooting an unexciting whiskey commercial, and Charlotte is lounging around the hotel as her husband works on photoshoots nonstop. The two protagonists feel lonely and isolated in this unfamiliar country. After spotting each other around a hotel, they go on excursions around Japan and forge a strange relationship that borders on both friendship and romance.

But, this “love story” — performed by a 52-year-old Murray and a 17-year-old Johannson, might I add — portrays Asians as homogenous, weird and perpetually foreign. This hackneyed and racist trope has implications beyond one film: It has been one of the pillars of systemic racism against Asians.

All of the Japanese women who appear in the movie are either service workers or sex workers. An extended scene features a female sex worker who offers Bob Harris “premium fantasy” and asks him to “rip [her] stockings” (she pronounces as “rip” as “lip,” which rattles Bob). I’m not amused when Asian women are constantly stereotyped as subservient and hyper-sexualized then murdered because of these racist stereotypes. Additionally, in the movie, Japanese men frequently shout, dance and use unnatural vocal inflections when speaking English. They also read explicit manga on subways and play loud arcade games; copious shots of Charlotte staring at these characters are littered throughout the movie. Juxtaposing the Asian characters with the baffled-looking white protagonists, Coppola clearly wants viewers to side with the “normal” white protagonists and think of the Japanese characters as strange. Asians are the butt of the joke; they must be labelled strange for the white protagonists to be likeable in comparison.

“Lost in Translation” exists to entertain many white Americans’ belief that they should never be required to put effort into understanding other countries’ lifestyles and traditions. The protagonists in the movie frequently show signs of frustration when interacting with English-speaking Japanese characters, whose fluency and pronunciation skills are sometimes not perfect.

The movie also relies on many white Americans’ real-world disdain for learning about other cultures and languages, a well-documented trend that puts Americans well behind even majority-white European countries in terms of knowledge of international affairs and levels of cultural competency. The characters’ frustration with English-speaking Japanese characters speaks to a larger trend of non-native English speakers taking on painstaking burdens to learn English, while Americans remain ignorant of or dismissive towards how the rest of the world caters to them. The majority (around 80%) of Americans only speak one language at home, but the majority of English speakers in the world are actually non-native speakers. Americans commonly mock and attack people who speak other languages and tell them to go back where they came from. We non-native speakers are told to make life easier for Americans, then insulted for it.

One of the most eye-roll-worthy scenes involves Bob Harris shooting a whiskey commercial. A Japanese photographer pronounces words that start with “R” as “L” (like “Rat Pack” and “Roger Moore”), and Bob Harris clearly looks annoyed and baffled at this different pronunciation. He makes sarcastic and snarky remarks throughout the photoshoot; he says in exasperation that he will drink as soon as he’s done.

The tendency for some Asian people to “mix up” Rs and Ls is a running joke in Western media that portrays Asians as unintelligible and hopelessly bad at English. Charlotte even asks, “Why do they switch the Rs and the Ls here?” Look, if you can understand what someone means, move on instead of getting bewildered at someone who speaks more languages than you. According to Coppola, the rest of the world should revolve around white Americans. I refuse to do that, and many others who are not white Americans would agree with me.

Certainly, not all white Americans show the egregious ignorance of the protagonists here. That is why “Lost in Translation” fails some groups of white Americans as well –– the movie does injustice to white Americans who are genuinely respectful, curious and thoughtful in learning about other countries’ or ethnicities’ cultures.

According to “Lost in Translation,” white Americans are the only ones who think and feel interesting things; other countries exist only to be playgrounds for them. The world is the white American’s oyster. White Americans can ignore the complexity of other countries to sulk in their feelings of alienation (which they caused for themselves), to think about the meaning of life and to cheat on their spouses.

Everyone else in the world has a nuanced understanding of white Americans through the media. Why? Because before perhaps the 2010s, when mainstream films like “Moonlight,” “Roma” and “Parasite” finally began to showcase complex narratives about non-white people’s lives, everyone was bombarded with stories about white people. We grew up watching the heart-wrenching romance of “Casablanca.” The sweat and thrill of “Rocky.” The brutal violence and cold ambition of “The Godfather.” Most media hammer the point home that white Americans have diverse lifestyles, perspectives and emotions. In the meantime, others are reduced to caricatures.

Applauding Coppola’s design of the movie only strengthens the racist structures that perpetually force Asians to be second-class citizens in the Western gaze. “Lost in Translation” is able to disguise its racist underpinnings by parading as a movie about loneliness and unlikely connections, which are much more appealing themes than racism. I am disappointed that so many critics and viewers choose to ignore or forgive the movie’s racism for the simple reason that loneliness is a relatable feeling. We must stop praising low-effort and discriminatory movies like “Lost in Translation” and turn our attention to authentic, nuanced stories that accurately present Asians as multidimensional people. I recommend films by Lee Chang-dong, Edward Yang, Wong Kar-wai, Yasujirō Ozu, Zhang Yimou, Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Satyajit Ray for such stories.

There are many terrific movies about feeling stuck in life and/or finding romance despite that struggle: “Synecdoche, New York,” “Punch-Drunk Love” and “Her” come to mind. “Lost in Translation” clearly tries to differentiate itself from these types of movies by selling culture shock as its distinguishing feature. Because of that strategy, Coppola is actively drawing attention to her racist narrative design — and my response is an emphatic criticism.