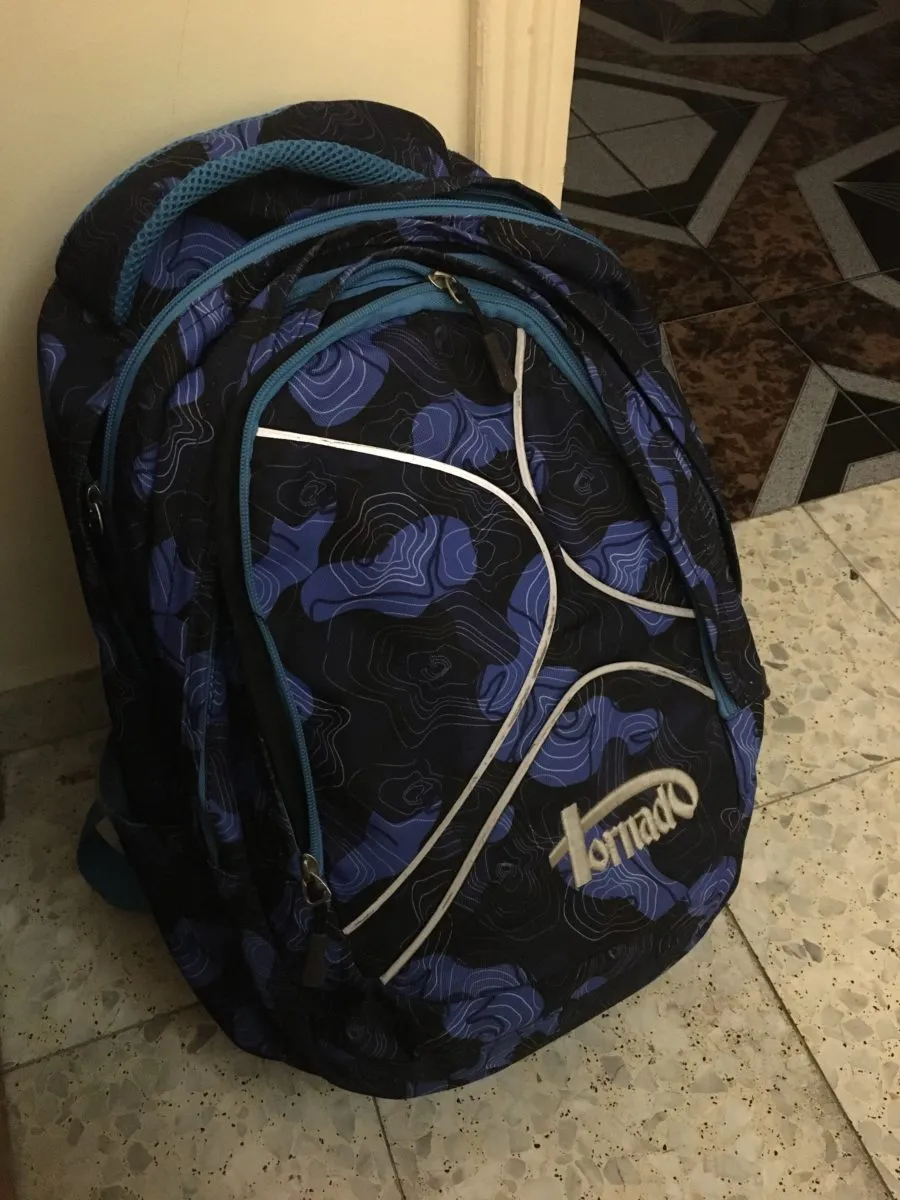

Yousef AbuHashem ’25 has kept a small backpack close to him since Israeli airstrikes targeting Gaza began 11 days ago. The bag is large enough to fit only the bare essentials: his birth certificate, passport, secondary school diploma, clothing and cash.

“When we hear that our house or any nearby building is threatened, we grab the bag and have to leave everything behind,” AbuHashem said.

If his home is bombed, the bag will be all he has left. It has already happened to a close family member. His uncle was awakened and swiftly evacuated when word came that his residential building would become the next target of Israel’s military operation in Gaza.

“They say only take the valuables,” AbuHashem said. “But the whole house is valuable — places are part of our identity.”

AbuHashem, 18, lives in Gaza, a Palestinian territory under siege by a barrage of Israeli airstrikes.

If it hadn’t been for the Israeli blockade on Gaza, a strip of land on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, AbuHashem would have been on Stanford’s campus, thousands of miles removed from the devastation in his homeland.

Instead, he is stranded in a territory where Palestinian lives are taken without warning and others, like his uncle, are granted only minutes to flee their homes. Israel’s 15-year air, sea and land blockade of Gaza, where AbuHashem has lived his entire life, has devastated the enclave’s economy, resulting in high levels of poverty and unemployment.

Conflict in the region, which has disproportionately taken the lives of Palestinian civilians, is not new, but this latest escalation is the deadliest and most destructive in recent years. Gaza medical authorities say that at least 227 Palestinians have been killed, including 64 children, over the last 11 days. Over 1,620 Palestinians have been wounded and 52,000 displaced, according to the United Nations. Israeli officials say at least 12 Israeli residents have been killed, including two children, by indiscriminate rocket strikes by Hamas, the militant group that rules Gaza.

The situation has become so dire that young Palestinians have resorted to drafting their own wills, AbuHashem said.

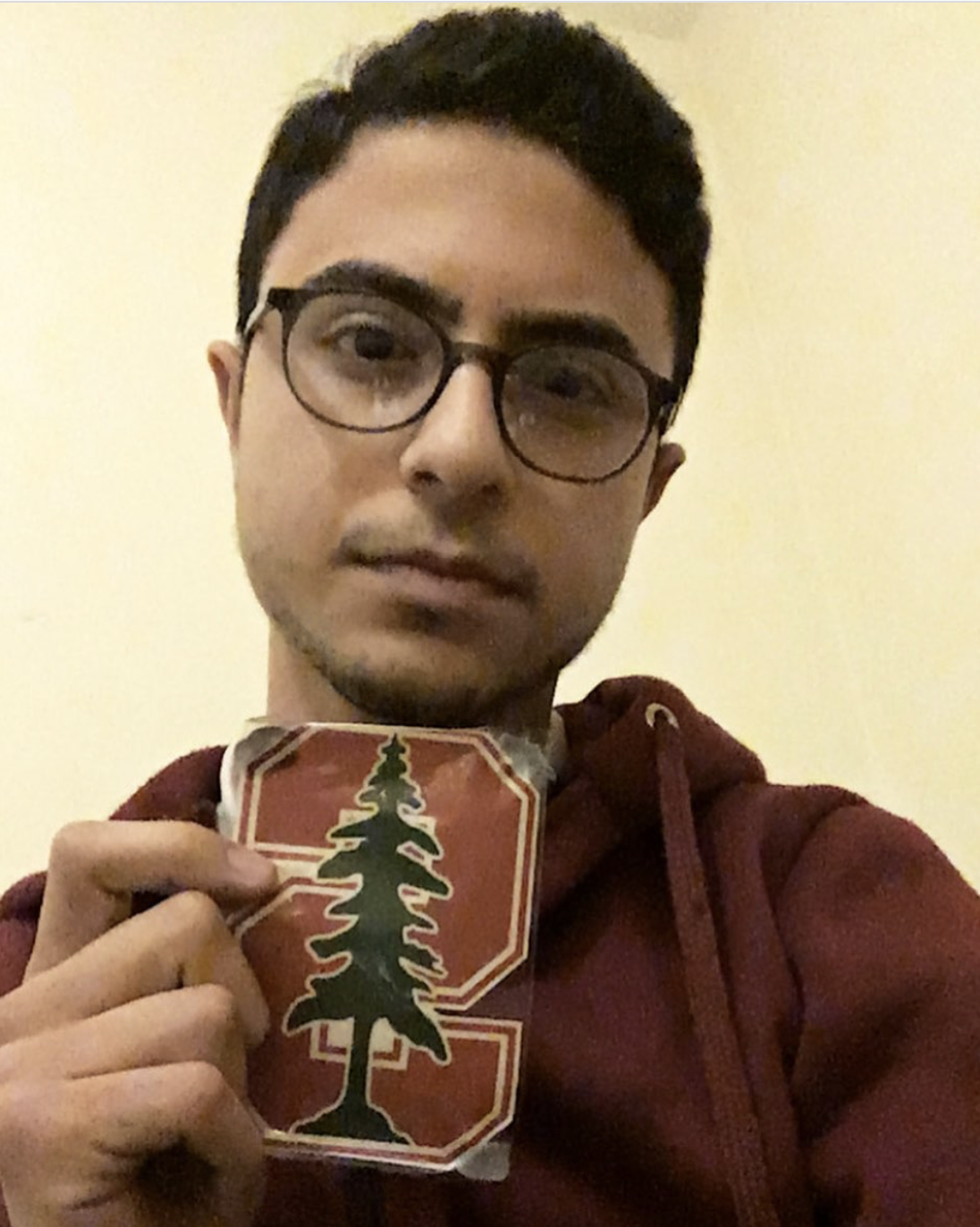

He too fears for his life. On Monday, AbuHashem posted on Instagram to explain the trauma he is undergoing and to call on Stanford to recognize the crisis in Gaza. The post has since gone viral, surpassing 92,000 likes in just two days.

“Right now, we’re under indescribable Israeli airstrikes for the 9th day in a row, and no one knows if we’re going to come alive out of this night,” AbuHashem wrote.

Doing the impossible

AbuHashem comes from a family of refugees. His grandparents, expelled from their homes during the Nakba — the 1948 Palestinian exodus in which hundreds of thousands fled or were expelled from their homes — were relegated to refugee camps before moving to Gaza. Now, both his parents are educators in the city. His mother is an educational supervisor at a school in Gaza, and his father works at an NGO that helps students apply for scholarships.

His parents’ experiences underscored the importance of education throughout his upbringing, which eventually led him to Stanford.

When he was admitted to Stanford last March, he was filled with an overwhelming sense of joy and optimism. For the first time, he thought, he could have a chance at a normal life and experience freedom outside the blockade. He had only been outside of Gaza four times, one of which was to see his brother graduate from Stanford.

“You see the letter and you think you’ve crossed the road,” AbuHashem said. “That you’ve done the impossible.”

But he was also worried he would not be able to return home if he left Gaza for Stanford. His brother, Abdallah AbuHashem ’19 M.S. ’21, has not returned to Gaza in over six years for fear that Israeli authorities would not permit him to leave.

Abdallah’s fears were realized when the younger AbuHashem attempted to leave Gaza for the United States to start Stanford in fall 2020 but was thwarted by the Israeli blockade. When the pandemic hit last March, Israeli authorities tightened their blockade of the region by temporarily closing the Gaza-Israel crossing point. Deterred but not defeated, AbuHashem took a gap year, hoping that as the pandemic subsided the Israelis would allow him to travel to Stanford.

But he said he lost that hope a little over 10 days ago, when the largest escalation in violence since the 2014 war in Gaza erupted between Israeli armed forces and Palestinian militants. Tensions reached a boiling point as Israel executed a series of raids on the Al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem and sought to expel Palestinian families living in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood. The conflict has since raged for days without any end in sight, although the international community has urged Israel and Hamas to agree to an immediate ceasefire.

For AbuHashem, Palm Drive now seems worlds away. He can’t block out the crashes of Israeli airstrikes that reverberate for kilometers in every direction or the horrific screams of wounded Palestinian men, women and children alike. Access to power and the internet are sparse and unpredictable, leaving many Gaza residents in the dark for hours on end.

AbuHashem says Palestinians are living day by day, hour by hour in fear.

“Every night we think of getting out alive, but no one knows if they will survive until the morning,” AbuHashem told The Daily early Wednesday morning, just seconds before an airstrike hit a nearby target during the interview. The blast wave that followed shook his desk. After a brief reprieve, two more strikes occurred within eight minutes of each other.

On the eighth night of airstrikes, not knowing when or if he would escape the violence, AbuHashem drafted a message on social media. Hesitant to make his statement public, AbuHashem initially scrapped the post entirely. But after heavy artillery shelled the city, “I just felt that I really might not make it,” he said.

He pressed “post.”

“If I wasn’t among you next Fall, if I became a number, remember me, remember my story,” he pleaded in the caption. “I am not a number, my name is Yousef.”

In the post, AbuHashem wrote that Stanford is turning a blind eye to the human rights violations in Gaza and that the University maintains ties with companies that operate or conduct business in Israeli settlements. The U.N. and most of the international community consider the settlements to be illegal under international law, although Israel disputes this.

In less than two days, AbuHashem’s message has garnered overwhelming support from the Stanford community and beyond. The post has over 92,000 likes and over 2,500 comments as of Wednesday night.

AbuHashem also called on students to send Stanford administrators a letter that was drafted by student activists. The draft letter urges the University to uphold its commitment to diversity and inclusion by issuing a statement to “acknowledge this ethnic cleansing” and “support and affirm your Palestinian students.”

A spokesperson for the University did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the matter. In a 2015 statement, the University wrote that it did not seek “to determine the veracity […] or disprove” claims that companies it had ties with profited from violations of human rights and international law in Palestine or Israel.

Stanford’s reticence to speak on the issue is consistent with the public stances of most colleges and universities in the United States. After the Undergraduate Senate passed a resolution urging Stanford to divest its endowment holdings of companies linked to Israeli activity in 2015, the University’s Board of Trustees declined to take a position.

“The University’s mission and its responsibility to support and encourage diverse opinions would be compromised by endorsing an institutional position on either side of an issue as complex as the Israel-Palestine conflict,” the board’s statement read.

In recent years, a growing number of international and Israeli human rights watchdogs have contended that Israel’s government is perpetuating apartheid and persecuting Palestinians under its occupation. The Israeli government considers these reports to be baseless attacks.

AbuHashem’s brother, Abdallah, a master’s student at Stanford and incoming Rhodes scholar, said that discussions of rights violations have little to no effect when institutions refuse to take action and hold others accountable. Abdallah said that the University is adept at providing individual support to students, “but they don’t like taking institutional action that can actually make a difference.”

“I don’t know what Stanford needs to deem the situation as not too controversial,” Abdallah said. “Stanford’s refusal to take action is a failure.”

AbuHashem said that although most of the world has long neglected the plight of the Palestinian people, the outpouring of support he received on his Instagram post could be indicative that the tide is shifting.

“In the midst of such horrifying reality, it is relieving to know that so many in the Stanford community are ready to advocate for me,” he said.

During the violent escalations, AbuHashem said that the humanity of Palestinians in Gaza is often forgotten or overlooked.

“We just want to have normal lives,” AbuHashem said. “We don’t invest in fighting and we don’t want to live under rubble. We are humans. We like to go out with friends. We listen to music.”

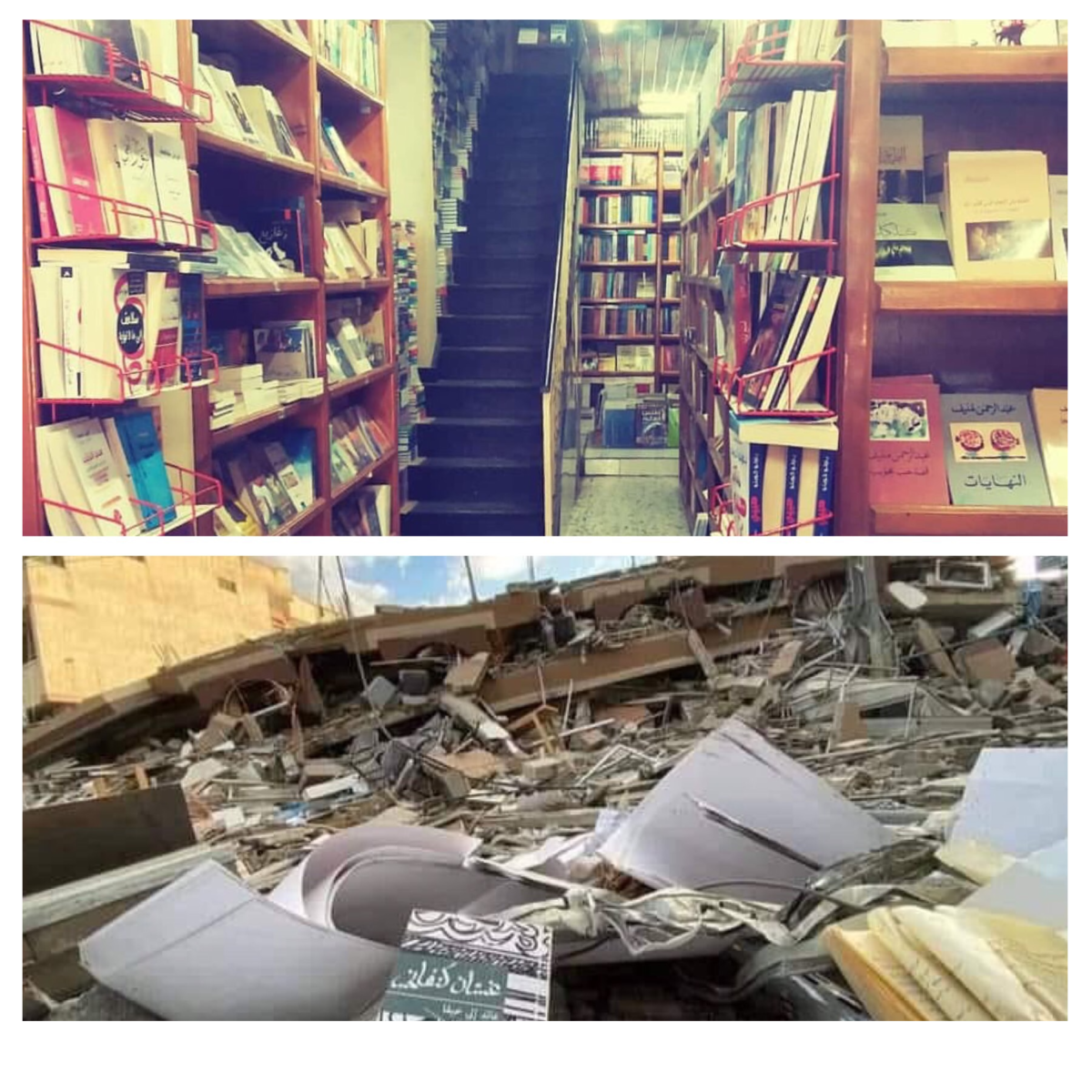

But every day, lives are ended and pieces of Gaza’s infrastructure are destroyed, bringing the city further from visions of a “normal” Gaza. An Israeli airstrike leveled the very bookstore where AbuHashem got his copy of Stephen Hawking’s “Brief Answers to the Big Questions.” Gaza’s only COVID-19 testing laboratory was damaged, and the main road leading to the enclave’s largest hospital was hit, blocking critical access to wounded civilians and health workers.

“I wish I was normal. I wish I did not have to experience and share such trauma,” AbuHashem said. “I wish I was a kid who could practice his right of education and freedom of movement away from fear and uncertainty.”