At the end of last year, as most of the world was trying to crawl out of a pandemic, the American judicial system was facing an altogether different challenge. “The addition of three conservative appointees by President Donald Trump in four years has disturbed the balance and possibly destroyed the comity of America’s highest court,” intoned an article in the Financial Times, after Amy Coney Barrett took the place of the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Three months earlier, in the same newspaper, Stanford Law School Dean Jenny Martinez mourned Ginsburg’s death and wrote:

If Donald Trump is able to name her replacement, that justice could tip the court’s current 5-4 conservative majority to 6-3. That would all but end the moderating role played by swing voters on the court over the past three decades…

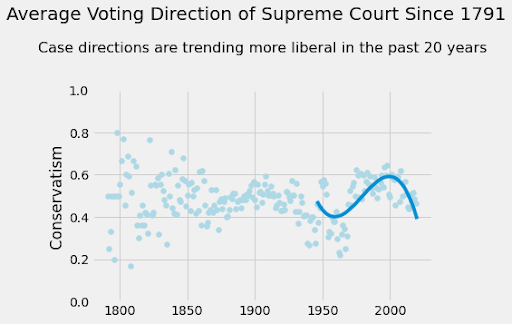

According to Pew Research Center, if you’re a Republican then you are likely to think that the Supreme Court is rather moderate. If you’re a Democrat, odds are that you believe the Supreme Court is mostly conservative in its decisions. The data, it turns out, says that the average voting direction of the court is actually trending liberal.

Before we look at that data, it helps to know what is being measured. What makes for a “conservative” justice? The answers broadly fall into three different categories. The first category is “judicial restraint,” which means the justice takes a narrow view of the Constitution and sticks to the “original meaning” of the document.

The second category states that conservative justices uphold the principle of stare decisis et non quieta movere, which means “stand by what has been decided and do not unsettle the established.”

Before we even get to the third category of judicial conservatism, we can already see the conflicts inherent in the first two. Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 decision establishing the unconstitutionalty of racial segregation in public schools, clearly ran afoul of “judicial restraint” because it thrust judges into the daily administration of school districts and so on. Yet no conservative candidate for a judgeship, advocating for “judicial restraint,” would oppose it. Stare decisis purists assume that justices are infallible. If they were guided by that definition, they would have to oppose overturning Roe v. Wade, the abortion decision that has stood for nearly half a century. And oppose Brown too, for overturning the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision that upheld racial segregation.

This brings us to the third category, whose believers simply brush past these conflicts and bluntly advocate a “conservative” ideology. A conservative justice, in this line of reasoning, is one who supports a certain political agenda, regardless of the contradictions it may suffer with the other two notions of conservatism or anything else. It’s conservatism of the vengeful variety; recompense for what “liberals” have done.

It is this third category, dissatisfying as it may be, that we will use to define conservatism. It does have a few things going for it. For one, the conservative political agenda is widely covered in the press, making it easier to label. It also avoids the “false binary” pitfall of the other two categories wherein real world data, such as ideological belief distributions, are continuous (like total marks earned by students enrolled in a course, from exams and assignments) and get arbitrarily broken into pure, discontinuous buckets (as with grades issued at the end of the course). The Martin-Quinn ideology scale, used by Washington University’s Supreme Court Database, is such a measure of conservativeness. It is on a sliding 0-1 scale. On this scale William Rehnquist ’48 MA ’48 LLB ’52, was the most conservative of the justices in recent memory. Clarence Thomas is the most conservative justice on the present bench and Sonia Sotomayor is its most liberal.

Among justices who are no longer on the bench, Kennedy’s conservative score may seem surprising, only because his record during his last decade on the bench was rather more liberal than his previous two decades. We will return to this point later.

The Database bears information about every case decided by the Court between the 1791 and 2019 terms. The Liberal or Conservative label is assigned to each case by the Database. This is not a sliding scale but binary. (Much like what a student scores on a single multiple-choice question; a 0 or a 1. We plotted the average values of each justice’s decision, which falls on a scale from 0 to 1, with increasing conservatism the closer the justice gets to 1.) So decisions favoring children, minority racial and ethnic groups, affirmative action, persons accused or convicted and environmental protections are all considered liberal. Decisions against such positions are considered conservative. Those cases that do not lend themselves as liberal or conservative or have no existing convention as to which is the liberal or conservative side have been excluded from the dataset for this analysis. For example, a case on boundary disputes might fall into the first category and the legislative veto may fall under the second category. We acknowledge that these cases might lend something meaningful, but decided against analyzing them in favor of clear cut conservative or liberal cases. However, we do encourage anyone who is interested in such cases to contact us or conduct their own analyses.

Analysing the entire dataset, we see that decision trends since 1946 reflect the liberal movements in the 1960s and subsequent conservative court in the 1980s. The right tail of the graph shows the gradual liberal-leaning trend of the court in the 21st century. Overall, the Court doesn’t deviate much from a moderate voting direction. There is a slightly sinusoidal curve that starts sparse but narrows into a clear curve, with the exception of the 1950s and ’60s. However, in the past 20 years, that curve is clearly trending liberal.

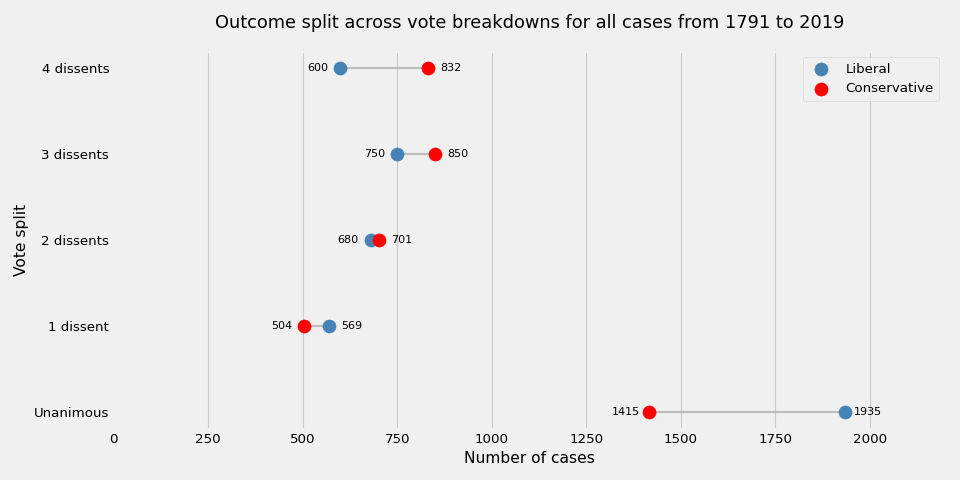

Nearly half of Supreme Court cases since 1791 were the result of unanimous decisions. In unanimous cases or cases with only one dissenting justice, the decisions were more likely to be liberal. However when more justices dissented, the outcomes tended to be more conservative.

A justice’s ideology really comes into play when the vote is pivotal and when there is a significant split between the justices. Many of these contentious cases are also high profile cases that are covered extensively by mass media. These cases with split votes tend to veer toward conservative directions, which might explain why many liberals and conservatives alike believe the court is not liberal-leaning.

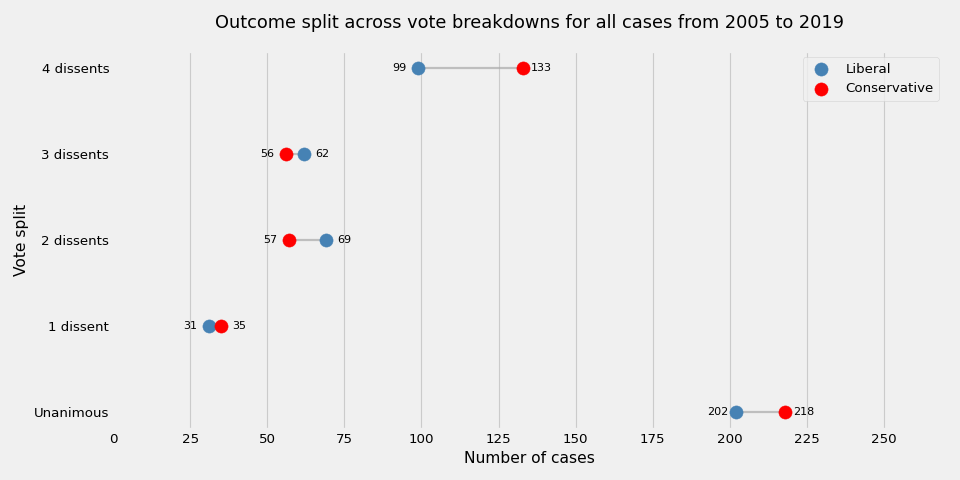

When we turn our attention to Supreme Court cases since 2005, however, a different pattern emerges. In these cases, unanimous decisions were nearly equally likely to have been liberal or conservative. Additionally, cases with two or three dissenting justices were more likely to lean liberal, in contrast to the pattern observed for all cases since 1791. Overall, the average voting direction remains more liberal than conservative.

This might raise some questions on how Supreme Court voting is conducted. Given that justices “sit around the table and…talk in order of seniority about the case—what they think the legal arguments are, and how the case should be decided…every justice will know how every other justice is planning to vote and whether their own vote could be the deciding factor in the case.” This suggests that decision directions are impacted by Justices knowing whether or not “their vote matters”; a ballot system in which every Justice is blind to the votes of the others until all the votes are tallied would yield a different outcome in at least some of the cases.

This brings us back to Kennedy, whose conservativeness dimmed when he became the court’s “median” justice after the retirement of Sandra Day O’Connor ’50 LLB ’52 in January 2006. Previously, he was often more conservative than her, casting a conservative vote in 75% of closely divided cases. Subsequently, being the de facto tiebreaker in an increasingly conservative court, he began voting in a liberal direction on cases involving criminal-justice, civil rights and due process.

The institution’s credibility seems to be an important factor in such shifts. After all, the Supreme Court depends on the rest of the government to fund it as well as accept (and hence enforce) its decisions. Our analysis suggests that the lifetime tenure as means to insulate justices from swings in public sentiments is overstated because it is offset by institutional-preservation tendencies. When rulings have deviated too far from public consensus, the Supreme Court has ended up adjusting, most famously in Justice Owen Roberts’s “switch in time that saved nine” in a minimum wage ruling. On a swathe of social and economic issues, the American citizenry has increasingly become liberal over the past decade. A Supreme Court that ignores this risks precipitating legislative action that negates the court’s influence. In 2007, when the court rejected an employment discrimination claim (Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber) by narrowly interpreting the six-month statute of limitations, Congress simply amended the law to allow such claims. Earlier in 1980, two years after the Supreme Court ruled against this paper in Zurcher v. Stanford Daily over police search warrants, Congress passed the Privacy Protection Act that provides additional legal protection against searches and seizures.

In recent years, the conservative Chief Justice John Roberts has sometimes provided the fifth liberal vote when he felt the court’s credibility among the citizenry was at stake, as in the 2012 rejection of a challenge to the Affordable Care Act. Those worried that Barrett’s arrival will disable the chief justice from making the difference on his own can seek reassurance in Neil Gorsuch (when he supported the 2020 LGBT protection under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act) and Brett Kavanaugh (as he hinted at the ACA hearing) becoming more sympathetic to Roberts’ efforts.

The liberal trends seen in our analysis suggests that the hopes of ideological conservatives, from a Supreme Court with three Trump appointees, are likely to be dashed. The court is an instrument of the government and therefore constrained by broad expectations set by the people. No grand judicial theory guides a justice to solve the major disputes that present themselves to the bench. We saw the inherent conflict in words like judicial restraint. Even esoteric-sounding ones like “textualism,” “originalism” and “intentionalism” fare no better. They too are subject to interpretation on god, guns, gender and green.

Sherwin Lai contributed to this report.