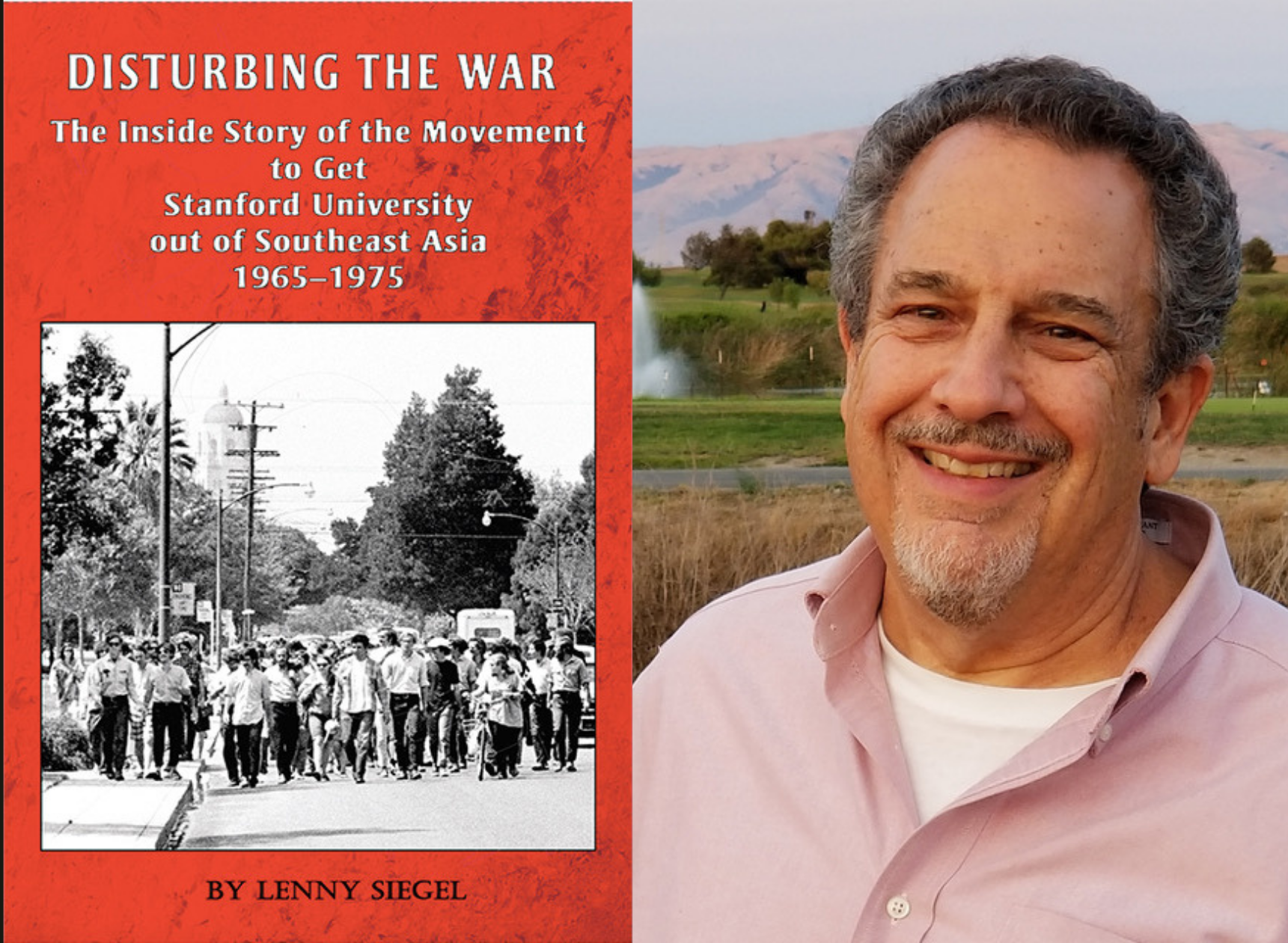

As my first year (virtually) at Stanford is nearing an end, I’ve been doing a lot of self-reflection on what it means to be a Stanford student, and especially what it means to have the political power that we wield. Recently, I had the chance to read Lenny Siegel’s “Disturbing the War: The Inside Story of the Movement to get Stanford University out of Southeast Asia — 1965-1975.” Structured like an autobiography, Siegel’s book offers valuable insight into his student activism at Stanford and his activism throughout his post-grad life, coming from someone who has dedicated his life to reform.

Before reading “Disturbing the War,” I had never heard about Siegel; the Three Books program Stanford created for frosh and transfer students unfortunately did not include a book like his that gives insight into how academic institutions like Stanford have fueled the military-industrial complex. As a result, many Stanford students today, myself included, may not expect that an academic institution like Stanford would have such a deep role in war efforts through its classified research in biological and electronic warfare. These studies brought in significant funding for the University, given they were of high interest to the Department of Defense — but they cast a shadow on the University’s morals and ethics as well.

“Disturbing the War” recalls how Siegel was involved in the anti-war movement and how Stanford students like Siegel fought to change research policies for greater transparency, calling out research that focused on death instead of life. Siegel’s and his peers’ efforts raised awareness of Stanford’s active role in the Vietnam War and shaped Stanford’s campus into a space for student activism.

In the book, Siegel details how student organizers worked to bring other students into their cause through educational discussions about how exactly Stanford was involved in the war, debates with fellow students on political theory and voting sessions to decide a course of action in response to the University.

Siegel’s story remains inspiring despite the desperation and frustration reflected in the knowledge that the University is heavily influenced by corporations rather than by the students themselves. These tumultuous years contained tense clashes with law enforcement on campus, and even the FBI was keeping tabs on the activities of student organizers. The rocky relationship between students and the University administration escalated, especially when Stanford dismissed tenured professor Bruce Franklin over being involved in the anti-war movement and “disrupting the peace,” raising questions about freedom of speech for not just students but also faculty.

“Disturbing the War” also brings light to the troubling nature of the right-wing counter-movement that was determined to bring the anti-war movement to its knees. Whether it was FBI surveillance or campus photography singling out protestors involved, anti-war student organizers felt as if they were fighting a battle on every front, with the odds squarely against them.

Thankfully, the story of the anti-war movement does not just end here, with the underdogs quashed by powerful Stanford trustees and FBI collaborators. Not every battle for the anti-war movement was a victory, but the movement left a lasting impact by forcing the University administration to reconsider research policy and reminding Stanford that its students were a force to be reckoned with.

Siegel’s detailed recollection of events during the anti-war movement also provides insight into how these student-activist organizations were structured. The anti-war movement brought professors and students together for class boycotts, teach-ins, marches and outreach beyond the campus. Original photographs throughout the book include documentation of student activities, often of them just sitting together, debating and discussing — modeling what Siegel calls “true democracy.” On multiple occasions, there were disagreements among the groups over the best course of action, resulting in the need for organizers to hold a vote.

As a student that values activism, “Disturbing the War” brought me some much-needed comfort and hope — especially at a time when the world is seeing the rise of social movements in response to authorities who fail to address racial injustice, settler colonialism and climate change, raising questions for many students regarding Stanford’s stance on and involvement with these pressing issues.