This article is the first of two installments in a series on Stanford’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. Read part 2 here.

Stanford’s entrepreneurial ecosystem is vast, catering to all students from aspiring startup founders to those simply interested in learning about startups. Like a biological ecosystem, it is a complex network of interdependent individuals, groups, relations and resources, but one that supports entrepreneurial education and the creation and growth of startups and ventures — brand-new companies or businesses.

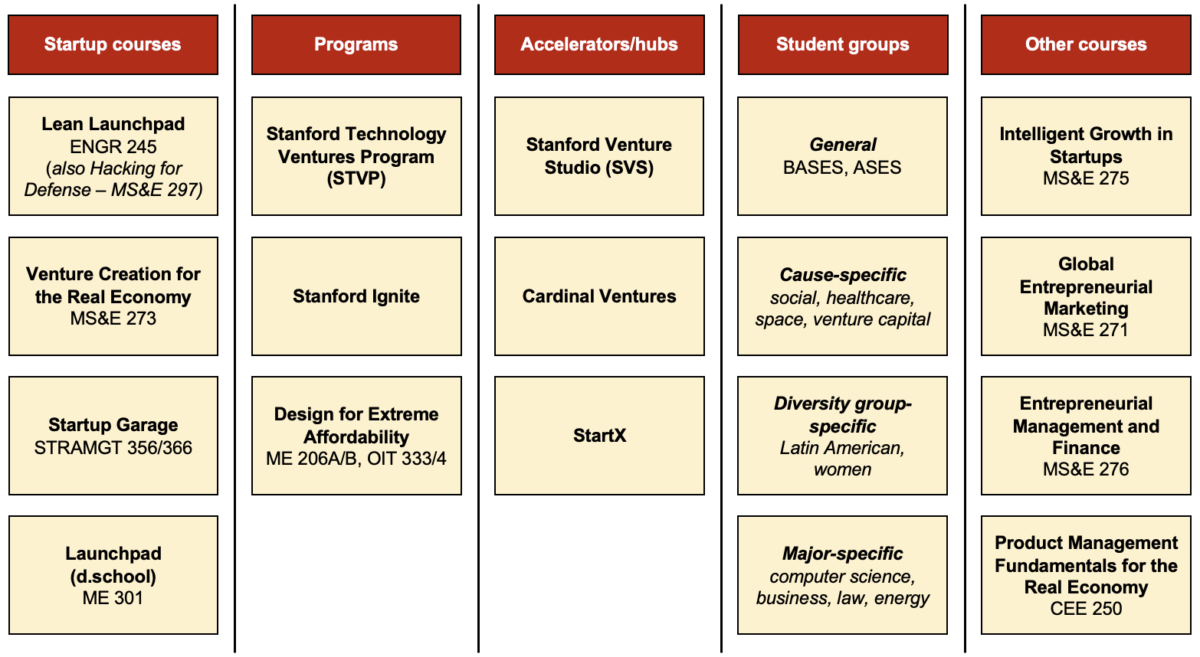

Such undertakings are typically very risky — about 90% of startups fail each year. Situated in Silicon Valley, a leading global entrepreneurial powerhouse, Stanford’s entrepreneurial ecosystem is well-equipped to de-risk, support and provide resources for these projects. In its current form, this ecosystem spans a labyrinth of courses, programs, accelerators and student groups, and can take ideas from conception to institutional funding and beyond while providing a vast network of entrepreneurs, investors and opportunities centered at the heart of Silicon Valley.

As a guide for the uninitiated, The Stanford Daily interviewed Stanford undergraduate and graduate students who have experienced the most popular of these resources.

A roadmap of resources highlighting some of the most popular parts of Stanford’s entrepreneurial ecosystem. (Graphic: Jonathan Ling)

While this series of articles aims to present the most popular and well-known resources that Stanford offers, more exhaustive lists are maintained by the Stanford Entrepreneurship Network and Cardinal Ventures. Course offering lists include those maintained by the Stanford Technology Ventures Program and Graduate School of Business.

Startup courses

Startups, or brand-new companies, begin with an idea — typically a solution to a problem, such as a product or service, that people need or want. With millions of companies in the world, coming up with a unique idea that is also monetizable for a profit is rare. Stanford offers startup courses that help students take an idea they have, develop it and test its appeal with potential customers. In all of these courses, students work in teams that resemble a small set of company founders. The courses also typically pair student teams with dedicated mentors and make available a wide network of startup and industry experts.

After the course, teams that wish to continue working on their idea often apply to more formal programs such as accelerators, apply for funding from investors and incorporate (legally register) as companies. Accelerators are fixed-term, cohort-based programs led by seasoned entrepreneurs that help startups establish a strong business foundation and fast-track their growth. Funding from investors is crucial to pay for the operational and legal costs of a startup before it is profitable, which could be many years later.

Stanford offers four major accelerator or pre-accelerator type courses open to students across all departments: Lean Launchpad, Venture Creation for the Real Economy, Startup Garage and d.school Launchpad.

Each of them is selective, with at least a written application required. Some of them have a follow-up team interview as well. Applicants can come with their own idea, which may be from scratch, or something they may have been working on for a while. Before applications are due, the teaching team typically facilitates mixers, which are events for students to meet others interested in the class, pitch potential ideas to work on and find teammates. Students then apply as a team with their idea, and the teaching staff review the applications.

Acceptance rates for the courses vary from 50% to 80% depending on the course. However, it is not uncommon for teams to change their composition after getting accepted, and students who did not get in at first may be able to join an accepted team if that team agrees.

Lean Launchpad teaches the Lean Launchpad method and is taught by its pioneer, professor Steve Blank. It is one of the most popular startup methodologies in Silicon Valley and beyond and focuses on developing robust business models — a plan for how a business sustainably makes profit — by interviewing and learning from customers to improve the business model in an iterative feedback loop. As such, it has a heavy emphasis on customer interviewing, requiring at least 100 in a 10-week period. The course is run in a flipped classroom style where students watch lesson modules online before each lecture then focus on their projects during the class.

Laura Sun M.S. ’20 was a member of the Lean Launchpad winter 2020 cohort and worked on building a platform to connect students with artificial intelligence tutors and research opportunities. A stand-out point of the class was putting professor Blank’s signature maxim into practice with a ferocious interviewing schedule.

“The real-world experience and the way of teaching which encourages students to ‘go out of the building’ to actually interview customers every week — that kind of experience really transformed my learning,” Sun said.

The course has a competitive application, so her team started planning the application three months before the start of the quarter, though many teams also form much closer to the start date. For a strong application, Sun suggests doing two steps.

The first is to meet with instructors: Sun and her team talked to Jeff Epstein, one of the other course instructors, several times at his office hours before applying. As a leading industry practitioner, she found his advice on how to structure the narrative of her application and startup idea very helpful.

“We pivoted even before applying for the class,” she added, after considering his advice, referring to the act of fundamentally shifting their business strategy to make it more robust. In the iterative development of a business model, pivoting is a common and important experience of startup founders, including during Stanford’s startup courses.

Her second tip is to have a great team — ideally, teammates that you enjoyed working with previously and have complementary skill sets.

“During our [application] interview, one question that we got was, ‘have you worked with each other or did you know each other beforehand?’ In the real world, it’s the same thing: When you’re pitching to a [venture capitalist], they want to know how you work with each other,” Sun said. Venture capitalists are investors in startups that provide funding after critically appraising the startup, which includes interviewing its founders.

Krish Chelikavada M.S. ’22, who was part of Venture Creation for the Real Economy’s spring 2021 cohort and attends the d.school Launchpad office hours, said that this point generalizes to all the startup courses: “It seems like it’s more about the team than the idea, because a lot of the teams that apply to these classes are very early-stage,” he said.

But even if you don’t know anyone else applying, there are plenty of resources to help, he said. In advance of the application deadline, the teaching team organizes networking nights, maintains a spreadsheet of other potential teammates on their website and facilitates the matching process, which most applicants use to form teams.

Hacking for Defense, also known as H4D, is a military applications version of the Lean Launchpad course, also taught by Blank in the same style. Projects include designing schedules to improve military operational efficiency, monitoring national security threats or designing new military-grade equipment. In addition to originating their own project ideas, students can also choose from a list of project sponsors from the military that have a problem they want to solve.

The class equips each team with one mentor from the Department of Defense (DoD) and one mentor from the business world. Both Lean Launchpad and Hacking for Defense typically accept eight teams per cohort, although this sometimes increases with higher demand.

Acceptance Rate: The acceptance rate for H4D was 50% in 2020, as per the 2020 team interviewing schedule.

David Mackanic Ph.D. ’20 successfully launched his flexible batteries startup Anthro Energy through the course as a member of the spring 2020 cohort. For him, insight into the military and government that the class brought was key.

“Understanding how to work with the DoD and the government is a crucial skill for many deep tech startups; however, this skill is very difficult to learn in a vacuum,” he said. “H4D combined an incredible network with plenty of hands-on mentorship to help us dive in and learn about how to work with the DoD. It was a lot of work, and certainly felt like a crash course, but I think that the totally immersive experience is necessary to make inroads to this unique customer.”

He also noted how the program contributed to his startup gaining traction after the course ended: “H4D opened up doors for us in terms of meeting advisors to our company, participating in a follow-on accelerator, meeting investors and obtaining [Letters of Intent] to help us win government grants.”

Venture Creation for the Real Economy, formerly Technology Venture Formation, is a second startup course offered by the Department of Management Science and Engineering, but has a greater emphasis on startup business fundamentals and concepts. Students also pitch to panels of professional venture capitalists and Silicon Valley industry experts who provide teams with feedback. Each team is paired with a mentor based on their experience and expertise with whom they meet weekly. The course also assigns roles to every team member: Chief Executive Officer (CEO), Chief Financial Officer (CFO), Chief Technology Officer (CTO) and Chief Marketing Officer (CMO). Like Lean Launchpad, it is taught in a flipped classroom style. Students can make extensive use of office hours to discuss questions with course staff and mentors.

Acceptance Rate: Twelve teams were admitted into Venture Creation for the Real Economy in 2020 at an acceptance rate of 63%.

Chelikavada, who is part of the spring 2021 cohort, aspires to build a startup that will help remote teams collaborate more effectively. He said that the course provides the mental models, frameworks and knowledge needed to run a startup and evaluate the startup idea, with a lighter emphasis on continuous interviewing. The syllabus includes creating some concrete plans and models, such as a product development plan, financial operating plan and financial model — as would be necessary for a real startup to have when pitching to investors and operating the company. Teams also get one-on-one feedback from an expert on their models.

Startup Garage from the Graduate School of Business is another popular course, which can be taken in the fall, winter or typically both. The fall quarter portion focuses on iteratively designing a solution while interviewing customers, while the winter quarter is about testing and launching the business. Mentors include founders and early executives of well-known Silicon Valley companies as well as seasoned VC and angel investors.

Acceptance Rate: Acceptance rates for Startup Garage have historically been around 80% for the fall quarter and 50% for the winter quarter.

Daniel Kharitonov Ph.D. ’21, a member of the fall 2020 cohort, worked on an idea to improve training for autonomous vehicles by augmenting fleet footage with synthetic data. Having also taken Lean Launchpad, he says that there are some minor differences between the two courses.

“Startup Garage lectures and assignments are more variable and structured [and it] also gives funds for experiments,” he said, referring to a $1,000 grant per team. In contrast, “Lean Launchpad has a better all-round structure and a stronger mentor network [with more] help in the interview pipeline.”

As for what it takes to be successful in Startup Garage, Kharitonov says to try to come up with customer traction insights — things that customers find valuable and would be willing to pay money for. Where most teams try to appropriate existing ideas or technologies to new types of customers, the lack of actual customer need or demand for them makes the startup fail, he said, stressing the importance of validating what customers really want.

The d.school Launchpad accelerator program runs as a 10-week course where students develop prototypes, find key customers and investors, prove viability and get to market by the end of the course. It’s taught by d.school professors Perry Klebahn and Jeremy Utley. Unlike the other three courses, the instructors emphasize that the program is an accelerator, not a class, meaning the goal is to get a product to the market by the end. Incoming teams are expected to end up launching as startups.

The program provides students access to an extensive startup network to leverage: lawyers, investors, market experts, Stanford alumni, mentors and workspaces in Silicon Valley. Students even get access to top industry accelerators, which unlike Stanford’s startup courses, take on startup teams from all over the country, have much more funding available and whose international recognition adds to the reputation of admitted startups.

Though Launchpad was canceled for the first time this year but will resume again next year, Chelikavada has spoken to founders who have graduated from the course. “They inspire you to do things that you didn’t think you could [such as] to 10x your sales in two weeks. They’ll help you come up with creative strategies in order to 10x your sales. So it really prepares you for that explosive growth mindset,” he said, a mindset that startup founders, who need to grow their businesses extremely quickly, find valuable to cultivate.

However, Chelikavada also regularly attends the office hours that the d.school Launchpad professors Klebahn and Utley hold every week, that are open to everyone, every year, and what he says is one of the most helpful resources on campus for him as an aspiring entrepreneur.

“It’s like a weekly check-in you do with them. They help you figure out what to do next, what you did well, what you didn’t do well. They’re super experienced, [having worked] with startups for like 15 or 16 years,” he said. “They’re very good at helping you de-risk your idea in the early stages — like how do you know your idea has merit? How do you know there’s a market for your idea? And they help you go even beyond just customer interviews.”

Should one do multiple of these courses? Kharitonov thinks that any one of them is sufficient to get serious teams to a stage where they can apply for bigger programs. “If your startup survived two to three quarters and has significant customer traction, it is more likely to land in [an] accelerator seed money fund than a class,” he said, referring to a type of accelerator that provides initial or “seed” funding to startups. “This said, d.school Launchpad is also not a bad option to develop customer traction if it already exists,” he added. “If that is not the case, taking a different entrepreneurship class only makes sense with a new team and a new idea.”