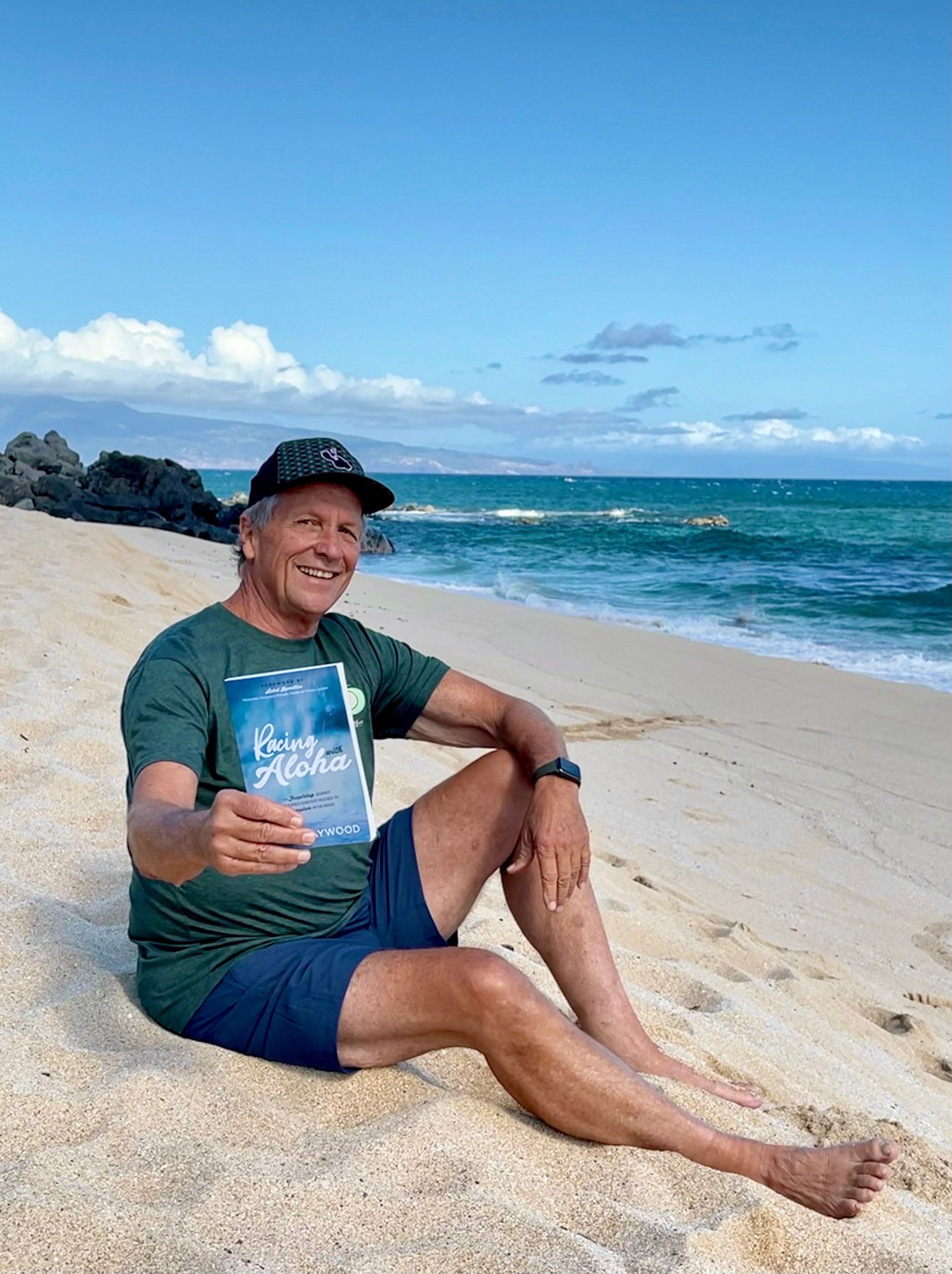

Growing up in Maui, Hawai’i, it’s difficult not to immerse oneself in multiple water sports. That’s what Fred Haywood ’71 did, swimming and surfing before he moved to California at age 17. His Maui upbringing led to multiple NCAA and American records in swimming, world records in surfing and sailing and now, an autobiography called “Racing With Aloha,” which is set to be released on Aug. 24.

Haywood’s swimming career began in the ocean, in an area in Kawaihae Harbor that was built as a raft and cordoned off with telephone poles and 60-gallon drum barrels. At Hawai’i Prep Academy, coach Jerry Damon would wake Haywood up at 4:30 a.m. three days a week and drive him to the harbor for a morning workout before he joined the rest of the team at their afternoon swim.

“I had to swim out and put a gas lantern on one side, and we had car lights on the other,” Haywood said. “I was the only one who was training in the morning, it was wild.”

The double workouts in the ocean swimming pool paid off, as Haywood moved to Santa Clara, Calif. before his senior year of high school to swim with the legendary Mark Spitz. Spitz earned nine Olympic gold medals in swimming over the course of his career, including seven at the 1972 Olympics in Munich while setting world record times in each event.

While Haywood attributes some of his success to Spitz, he also considers former Santa Clara teammate, Mitch Ivey, to have been a formative influence. Early in Haywood’s senior year at Santa Clara, Ivey told him that he had “the ugliest backstroke he’d ever seen.”

“I had to go underwater and blow bubbles for a minute and unclench my fist after I heard that remark,” Haywood said. “And I came up and I looked at him and said, ‘Well Mitch, you have the prettiest backstroke I’ve ever seen in my life. What do I have to do to look like you?’”

Ivey demonstrated the proper technique with a towel and told Haywood to practice it during their break between swimming intervals. And for the last 10 reps, Haywood swam faster than Ivey, whom he described as “the best backstroker in high school.”

Santa Clara coach George Haines timed Haywood in the pool a few days later, and Haywood, swimming the 100-meter backstroke by himself, finished in a high school record time of 54.0 seconds. Haywood, Spitz and Ivey traveled to the 1967 NCAA National Championships two weeks later (when high school swimmers were able to compete at NCAAs) and Haywood won the 100 backstroke in 52.6 seconds, surpassing his own national high school record and beating out older collegiate athletes in the process. The performance earned him numerous offers from universities around the country, but the Farm was ultimately where Hayward would decide to make his home. He matriculated in the autumn of 1967.

Once at Stanford, however, he struggled with his classes almost immediately. Calling his father, he told him he wanted to come home.

“And he says, ‘Like quit?’” Haywood recalled. “I said, ‘Well no, just take a break.’ He says, ‘Well, you know you have the rest of your life to make a decision to quit. Why don’t you just give it two weeks and call me back?’ I never called him back.”

While Haywood did swim for a year at Stanford, his swimming career came to an unexpected close after the 1968 Olympic Trials due to medical challenges. He earned a degree in economics from Stanford in 1971 and returned to Maui to work in construction, at a restaurant and eventually in real estate.

“I decided I’d try to get into real estate so that I could buy a ticket to Indonesia and go surfing with my friends who were adventurers, and they said that they had found the best waves in the world down there,” Haywood said.

His first commission allowed him to buy a ticket to Bali, where he lived for two months and surfed daily. Haywood also explained that he wanted a job where he could work in Hawai’i during the winter and summer selling real estate and travel to surf during the fall and spring seasons.

“[Bali] just opened my eyes to opportunity. I just said, ‘Well, life’s gonna be what I make it and it’s meant to be,’” he said.

While living in Kaanapali and working in the real estate business, Haywood saw two windsurfers sail onto the beach for the first time. He ran down to meet them and to learn how to windsurf. He quickly became hooked on the sport that would fuel his next water adventures.

“I learned how [to windsurf] quickly and I just wanted to go sail every day,” Haywood said. “About the same time, that was probably seven or eight years after Stanford, and I was just yearning to do something successful.”

Following the death of one older brother in a traffic accident, he left the real estate business and opened a windsurfing shop, Sailboards Maui, with friends Bill King and Mike Waltze. King and Waltze happened to be the two windsurfers who Haywood saw sailing into the beach in Ho’okipa on what he called “that fateful day.”

Ho’okipa, Haywood explained, always has “incredible wind and waves” due to its location between two mountain ranges with a flat plain in the middle. The geography lent itself well to speed sailing, a sport where participants aim to complete a predetermined route as quickly as possible.

And Haywood, of course, found yet another water adventure in speed sailing, even traveling to Weymouth, England in 1983 to break the world speed record on a windsurfer. He was the first sailor to record a speed of greater than 30 knots — slow compared to present-day times, which, depending on the distance, can be as fast as 65 knots, but nevertheless impressive in the 1980s.

“I came home [to Hawai’i] after doing that and four months later I rode a really big wave in Ho’okipa, it was probably 50 feet, and put myself on a bunch of covers of magazines, again, just three or four months after breaking the world speed record,” Haywood said. “My sponsor [NeilPryde Sails from Hong Kong] said, ‘Well, that was the biggest one-two punch into a sport I’ve ever seen!’”

Hearing Haywood talk about his father, Guy Haywood, it’s easy to see where his adventurous spirit came from.

Haywood said his father would tell stories about his great-great-grandfather and the wild things he would do.

“He’d bet a guy a horse and saddle that he could ride a buffalo across a particular river. So, he climbed up in a tree and waited for [the buffalo] to pass underneath the tree and then jumped onto the buffalo and rode it across the river and won a horse and saddle,” Haywood recalled.

His father, who supported Haywood’s move to California in high school, was also a proponent of living a constantly changing life until something more interesting and more satisfying comes along. Following his graduation from Stanford, Haywood asked his father what he was supposed to do with his life.

“He says, ‘Well that’s something you’ll never know. You’ll only know that you have to get busy in life and find out what’s interesting to you and move toward it,’” Haywood said.

Similar to the death of his older brother spurring the creation of Sailboards Maui, the recent death of his younger brother inspired him to start his next adventure, for which the proper opportunity had never presented itself, although the interest had always been there — writing a book.

“I wanted to write the book for the last 54 years because my rise to stardom in swimming was so electric, so fast, so beyond my greatest dream,” Haywood said. “And then it turned into getting into Stanford; it just kept on going.”

Haywood added the word ‘aloha’ to the title because, to him, it means to do something with love.

“If you spin it in a very positive way for other people and don’t do anything but bring ‘aloha’ into the work that you do, life will open up for you because people respond to love and not negativity,” he said.

“Racing with Aloha” is currently available for preorder on Amazon.