Certain additives can strengthen vaccines to protect the body from a broad range of viruses, researchers at the Stanford School of Medicine found in a study published in late June in Cell.

Their results give new insight into the effects of vaccines on the immune system and methods to handle future epidemics and pandemics.

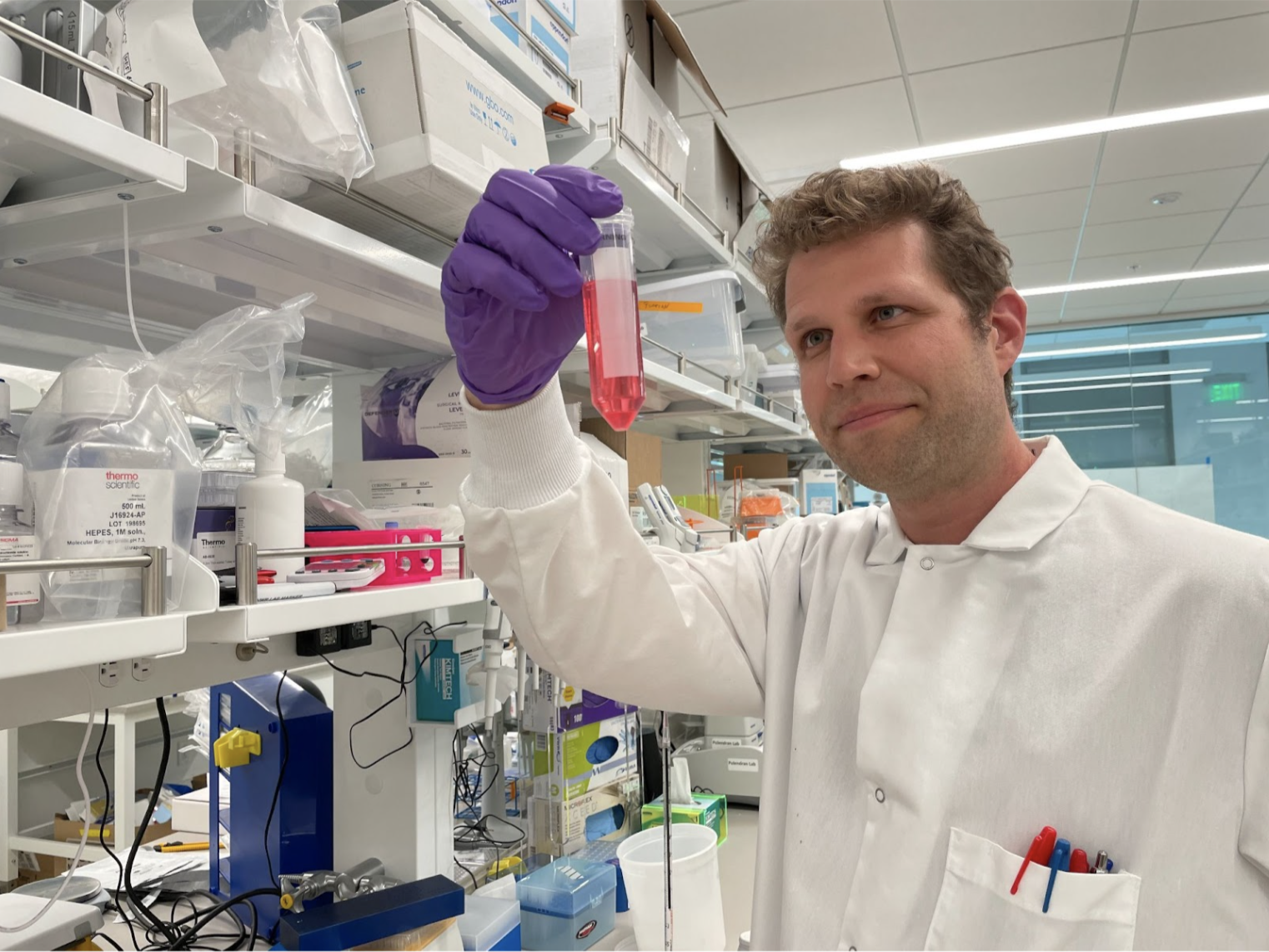

A team of 23 researchers concluded that adding an adjuvant — an ingredient that can increase the body’s immune response — causes certain vaccines to activate more antiviral genes. When a patient receives such a vaccine, they could gain protection against all types of viruses up to months after the dose, according to lead author Florian Wimmers, a postdoctoral fellow in the Institute for Immunity, Transplantation, and Infection.

“It could open up a new class of vaccines,” Wimmers said.

The study comes during a global effort to vaccinate against COVID-19, especially in light of a new delta variant which spreads quickly and easily. While we now have a COVID vaccine, Wimmers said his research could give scientists a new tool to save lives in the midst of an unforeseen pandemic.

The research’s outcome could create solutions for health crises similar to the beginning of the COVID pandemic, according to Wimmers. In early 2020, scientists did not have reliable ways to contain the spread of the virus and didn’t know a lot about it. “You could give people these nonspecific vaccines, and they would provide a certain amount of protection against any virus they encounter — including this new, unknown, emerging disease,” he said.

A vaccine stimulant that gives protection against unrelated viruses could affect many aspects of the field of immunology, wrote Tamiko Katsumoto, a clinical assistant professor of rheumatology and immunology unaffiliated with the study. The recent discovery “provides exciting possibilities for future vaccine development efforts and carries important implications in light of our current global COVID pandemic,” she added.

With the emergence of COVID-19 in January 2020 and the first administered vaccinations in December, it took nearly 12 months to successfully develop a vaccine. This speed was “superb,” said professor of microbiology and immunology and the study’s senior author Bali Pulendran. “But I would say that 12 months was 12 months too many,” he added, recounting the hundreds of thousands who died and the millions infected during the time range.

Pulendran said that immunizations with adjuvants, which might be administered in local pharmacies, have the potential to deliver broad protection to people while the medical community searches for a more specific vaccine.

“This immune stimulant we discovered here might also be beneficial in vulnerable populations to provide extra protection,” Wimmers added.

In the study, the School of Medicine researchers focused on the H5N1 bird flu vaccine when supplemented with the AS03 adjuvant, a chemical with vitamin E, used in healthy participants. They found that the modified dose made epigenetic changes to immune cells, meaning they temporarily impacted genes without affecting their DNA. Then, “whenever any virus came into the picture, those genes could now be quickly expressed and launch a rapid attack,” Pulendran explained.

The scientists infected the immunized cells with Dengue and Zika viruses – pathogens that Pulendran described are as unrelated to bird flu as “an orange is different from a watermelon.” Despite the difference, those cells had heightened and active defenses compared to those that had been given a bird flu vaccine without any adjuvants.

Though vaccines have seen use for over 200 years, much about the complex workings of the immune system is still being uncovered. Pulendran said that this research has brought a new understanding to the innate immune system. While the body’s adaptive response remembers viruses it encounters, the innate response reacts immediately to every type of virus — and was previously thought to not have a long-term memory.

“We have shown that the innate immune system, contrary to what the textbooks have said, also launches a response that can last not just for a few hours or days, but for weeks and perhaps several months,” Pulendran said. “And this response is able to resist any kind of viral infection.”

Wimmers will continue studying the interactions between the AS03 adjuvant and other types of vaccines to look for similar results: “Can we use this AS03 immune stimulant, or similar immune stimulants, to protect entire organisms?” Now that he knows how single cells respond to the adjuvant-enhanced vaccine, he wants to see how his experiment can be expanded.