Alice Cha carefully places a surgical mask on top of her N95 before donning her face shield. With full protective equipment, she climbs up steps to treat her patients hospitalized by COVID-19.

On the third floor, a fan in each COVID-designated room continually blasts to create enough ventilation to protect against the airborne spread of the virus. “You are sitting alone in a room where the fan is churning very loudly, and you are trying to do your best to breathe,” Cha said of her patients.

At Stanford’s ValleyCare Clinic, Cha routinely carries seven-day shifts as a hospitalist in the health facility. “We’ve been extremely, extremely busy,” she said.

Though Cha said that Palo Alto and Stanford Health had seen a decline from the pandemic’s surge, over the past month cases “have really ramped up again.”

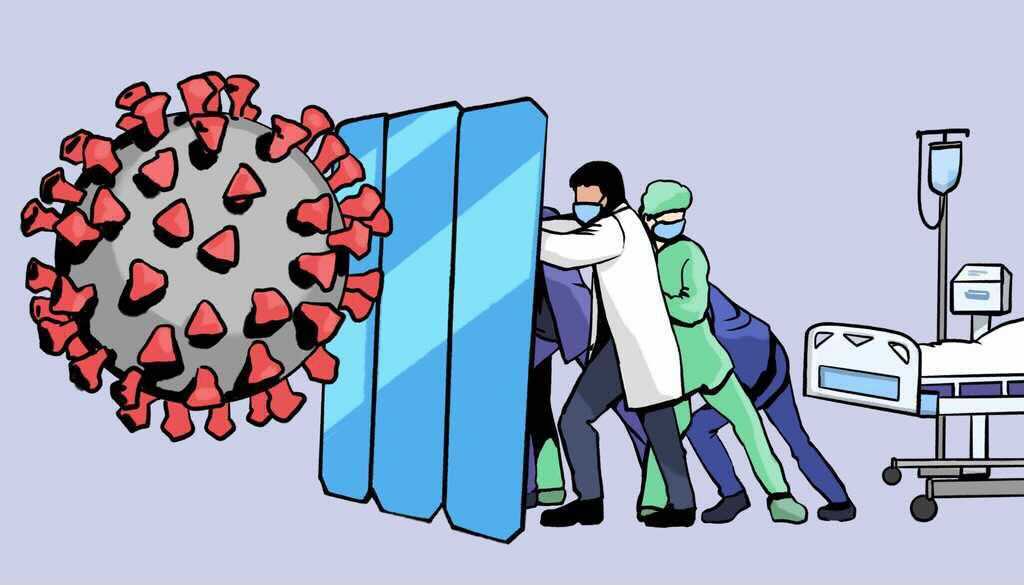

Health care workers such as Cha have faced continuous waves of cases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite the protection of vaccines, California’s rise in Delta variant cases has spurred serious concern among Stanford Health Care providers, who have watched the variant virus become a dominant form of COVID-19.

The current infections being treated are “almost exclusively Delta,” said Neera Ahuja, the chief of hospital medicine and director for general medicine inpatient wards at Stanford Hospital.

Ahuja’s ward treats all of the hospital’s COVID-19 patients who are not admitted to the intensive care unit. In June, the ward saw a record low in cases since the beginning of the pandemic. As the spread of the Delta variant progressed through the middle of July, the number of COVID-infected patients reached a peak of 13.

On a computer screen, Ahuja meets over Zoom with family members of infectious patients. Maintaining communication with loved ones who are not allowed to visit active patients became a focus for Ahuja during the pandemic. “We started meetings at seven in the morning, and I would sometimes be on until eight or nine at night,” she said.

As the leader for many hospital faculty, Ahuja communicated through many emails and adjusted to the shifting nature of COVID-19. Along with being a parent to young children, “balancing all of that was truly, truly crazy.”

Jeffrey Chi, who completed Stanford’s Internal Medicine residency in 2008, is a hospitalist at Stanford Health overseeing the staffing of COVID-19 response teams. He said that the hospital’s physicians from the ICU and various departments worked to treat the swell of COVID patients during the winter of 2020. They also took in patients transferred from nearby hospitals that had been overwhelmed by the new cases.

“Fortunately for now, we have not had to mobilize our COVID surge teams,” he wrote to The Daily. “But we are already starting to plan in case this becomes necessary.”

Remembering the hospital’s experience with surges before the Delta variant, Chi said that some nervousness has resurged as cases have. “It’s not like it was in February just yet, but I think what we’re worried about is that we’re already seeing increases in respiratory viruses, which normally don’t occur in the summertime,” Chi said.

Amid the continual treatment of patients and “disheartening” sight of a spreading Delta variant, Cha said the strain of the pandemic has taken an emotional toll on her and her colleagues.

Before the introduction of the vaccine, Cha’s mother — also a healthcare worker — treated cancer patients despite the high risk to herself. Cha’s colleagues have stayed in hotel rooms, afraid of transmitting the virus to elderly parents or their young infants. The rapid increase in Delta variant cases has added yet another burden to the health field. And unspoken depression among health care workers has “blossomed” in the pandemic, Cha said: “It’s emotionally scary for us.”

Like in much of the United States, most of the COVID-19 patients currently seen by Stanford Health Care are unvaccinated, according to Ahuja. Throughout the spread of the Delta variant, the director said that “what continues to surprise me is the resistance toward vaccination.” A number of the patients Ahuja spoke with had the ability to get vaccinated but chose not to.

Meanwhile, her experience working through the COVID-19 pandemic has also highlighted the vaccination struggles of underrepresented, minority groups to Ahuja. One of her patients shared fears with Ahuja that taking time off to get the vaccine would cause him to lose a day’s income. He couldn’t afford to miss even more work if he faced any harsh side effects, such as chills or nausea that can arise after a dose. The primary breadwinner for his family, he heavily relied on his daily income.

The story is not one-of-a-kind. In the heights of the pandemic, low-income and minority groups, such as those of Hispanic and Black backgrounds, were disproportionately hit by infections and deaths. As vaccine rollouts increased in the United States, many of these same communities held relatively low vaccination rates.

Asked about the most important part of changing the outlook of the pandemic for those who are able, Cha had a clear message: “Get vaccinated. Period.”

Ahuja urged those who are beginning to return to in-person and indoor spaces to wear masks, continue social distancing and remember that COVID-19 has long-term symptoms which can last long after the initial infection. “Find ways to take care of your mental health,” she added as advice for people such as students returning to on-campus environments.

Through the changing landscape of the pandemic, Cha relies on her team of fellow hospitalists both for her daily work and for hope looking into the future. “You learn to get to know a lot of the staff here,” she said. “So it feels like a cohesive group, a cohesive family.”

“The people around me are here for the right reasons. I see a lot of motivation to take care of people, a lot of selflessness. There’s no hesitancy to do their job.”