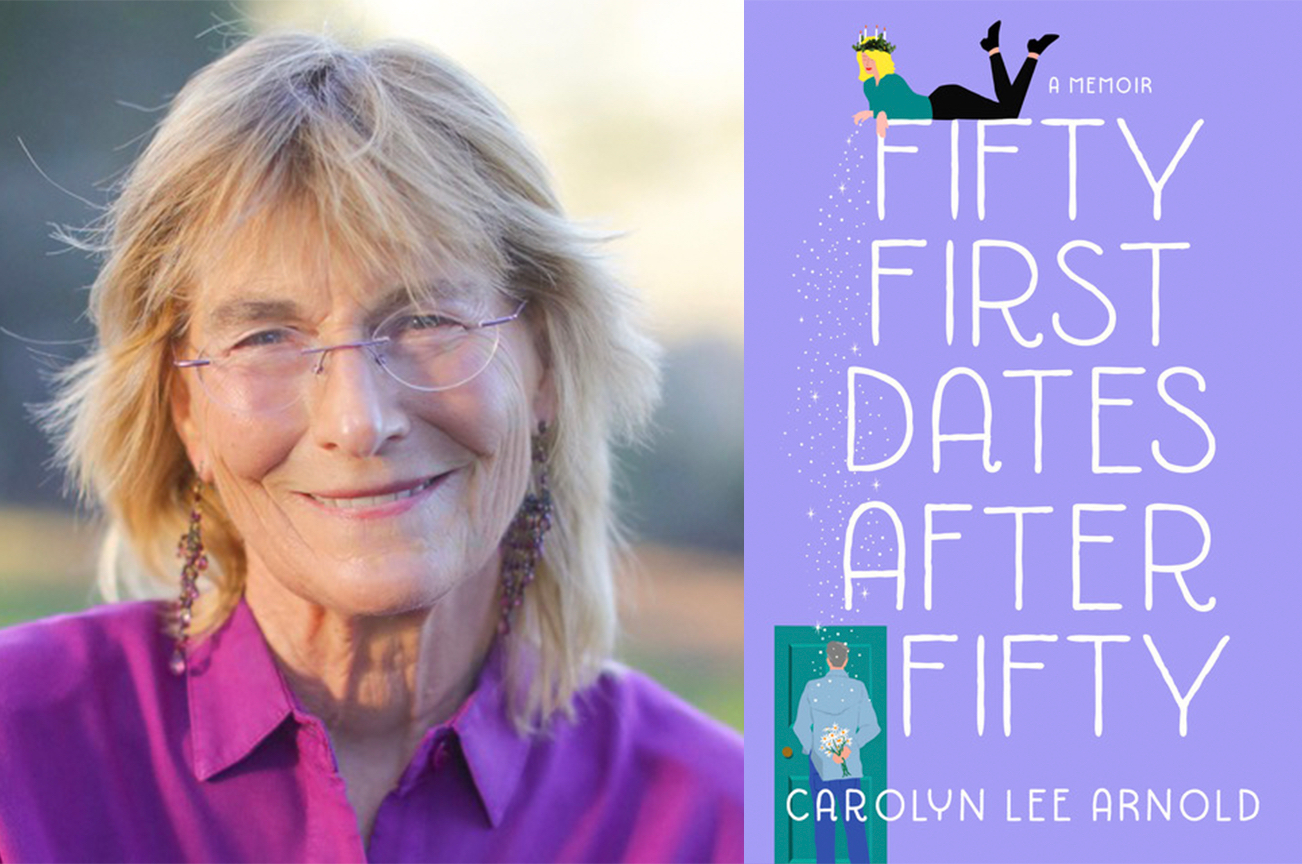

“It started in 2008 in the fall, right around now,” Carolyn Lee Arnold M.S. ’85 Ph.D. ’88 said of her two-and-a-half-year dating experiment that became the subject of her first memoir “Fifty First Dates After Fifty,” released to the public on Tuesday.

After breaking things off with an ex-boyfriend who couldn’t seriously commit, Arnold set out to find her long-term partner precisely how a seasoned statistician would: by transforming dating into an experiment. She resolved to go on fifty first dates, refining her own ideas about what she wanted in a partner along the way, in order to find the “perfect one.”

“It was natural for me to make it a research project,” Arnold said. When she began her project, Arnold had already been working as a social science researcher for fifteen years. She knew from her professional experience that samples of only fifty were needed for statistically significant results, and thus she decided fifty dates would be sufficient for her purposes.

Though Arnold’s idea for the experiment came to her quite suddenly, it took her much longer to realize she had the makings of a memoir.

“Originally, I just thought I had a lot of great stories,” Arnold said. “But when I was sharing my experiences with my friends, they said, ‘these are great stories — write them down!’”

Purely for her own self-care, Arnold kept a journal cataloguing her thoughts and feelings throughout her dating research project, and in the two years after concluding it, she made additional notes about all 50 dates.

“I’m so grateful they jogged my memory,” Arnold said. She then spent her weekends and summers from 2011 to 2018 turning these notes into a manuscript. In order to refine her creative writing skills and create enough structured time to execute the project, Arnold started attending memoir workshops.

“It wasn’t until I started taking memoir classes that I realized how to write a good story,” Arnold said. The workshop-style feedback loop gave her a better understanding of what readers might want from her book, and her teachers equipped her with tools for organizing the book’s central themes. One course that Arnold said was particularly pivotal in her project was Julia Scheeres’ 2011 memoir-writing workshop at The Writer’s Grotto in San Francisco. Scheeres, a journalist and author of the New York Times Bestseller “Jesus Land,” said that she was pleasantly intrigued by the fun premise of the dating memoir.

“I teach a lot of memoir students, and most of them are coming to the classes with really sad, tragic stories,” Scheeres said. “It was refreshing to have this fun, quirky, life-affirming story, and especially one about an older woman who is very sexual and very assertive.”

Arnold’s memoir is unapologetically genuine, manifesting its authenticity most prominently in its comfort around the subject of sex. According to Scheeres, workshop participants were at times taken aback by this element of Arnold’s writing, so Scheeres grew accustomed to prefacing her work.

“She’s always been this very liberated woman, but most people don’t think like Carolyn does,” Scheeres said. Nonetheless, Arnold’s authentic storytelling reflects “the beauty of these types of memoirs: they are glimpses into other worlds and to other ways of being.”

Arnold’s dedication to authenticity also explains her affinity for memoir as a medium. Awkward sexual encounters and sob episodes over her ex-boyfriend are sprinkled throughout the book, making Arnold a relatable character.

“I wanted it to be very real. I feel a passion, since I’m an early sex educator and a feminist, to represent women’s lives as they actually are,” Arnold said.

In the same way her participation in memoir workshops influenced Arnold’s writing process, Arnold said her involvement with the Human Awareness Institute (HAI) shaped her dating experiment.

HAI is a global nonprofit that produces research about and hosts workshops on love, intimacy and sexuality. HAI Marketing Director Kate Snow said that the organization aims to “increase people’s connection to each other and also to themselves in a very open and accepting environment.”

Arnold identified as a lesbian for 18 years, working with a tightly-knit community of women at the Berkeley Women’s Health Collective for four of those years. Eventually, though, she realized she wanted a long-term male partner. She left her community in Berkeley and began dating men, though not with much luck.

“I’d been seeing men now for 10 years, and just failing miserably,” Arnold said. “I was kind of in despair about dating. Then one of my ad dates from the newspaper took me to this HAI party, and the people were really nice.”

Though Arnold referred to the intimacy exercises conducted at the HAI gathering, which included gazing into a stranger’s eyes and gently touching their face or sharing affirmations, as “Psych 101” content, her deep longing for community got her to return. Her second experience was much more profound and had her hooked.

“I cried in somebody’s arms that night. I said ‘I think I need this,’ and I was at [another HAI] workshop the next weekend,” Arnold said.

Arnold credits HAI’s workshops with teaching her to be brave, communicative and assertive in her relationships — all traits that facilitated her dating experiment.

Throughout her fifty first dates described in her memoir, Arnold negotiates levels of intimacy with her dates. Time and time again, she skillfully communicates her relational and physical boundaries. She writes, “Ten years of workshops on relationships had taught me the concept of being ‘at choice’ — that in every moment, I can choose differently.”

“We layer in the awareness of ‘you are always at choice’ in everything that we offer,” Snow said about HAI. Arnold referred to this tenet of a healthy relationship when synthesizing the central message of “Fifty First Dates after Fifty.”

“I want women to enjoy dating from a place of self-love and self celebration, and if they want, I want them to be able to include sexuality in their dating; I want women to have choices,” Arnold said.

Arnold ultimately hopes her book models healthy dating and empowered womanhood, combating a negative stigma that women over a certain age can’t be picky about their partners.

As Scheeres said, “society wants to say, ‘by the time you’re 30 it all starts going downhill, and after 35 your fertility is gone and after 40 nobody wants you.’” But role models like Arnold are steadily eradicating these misogynistic myths. In moments when Arnold doubts the consequence of a fun memoir about dating, she reminds herself that this kind of visibility is actually a new advocacy.

“I look back to my younger feminist self, and I’m very proud of her,” she said. “But I think my younger feminist self would be proud of me, because I am being brave as an older woman to be dating, sexual and promoting older women being sexual. That’s what we were fighting for in the ‘70s.”

In many ways, Arnold’s dating experiment and memoir-writing experience were personally formative. She grew to love her own adventurous spirit and learned to speak gently to herself during bouts of hopelessness. In addition, the memoir’s happy ending is a comfort to readers.

Every year, Arnold holds a winter solstice ceremony where she and her friends reflect on what they want more and less of in the coming year. She focuses on this setting in her memoir’s epilogue.

“It really hit me that solstice 10 years later,” she said. “I didn’t have anything to let go because I loved everything about my life, and everything I was doing was what I had wanted during the dating project.” In the epilogue, intimate scenes between Arnold and her partner — date number 49 — are paired with moments from this solstice ceremony to give us a sense of closure. Her turbulent, laborious and zany dating research project had culminated in peace.

As Arnold concludes her memoir, “It must have worked.”

This article has been updated to reflect that Arnold received her Ph.D. in ’88, not ’98, and that she identified as a lesbian for 18 years, but worked at the Berkeley Women’s Health Collective for only four of those years. The Daily regrets this error.