Students in fall quarter Stanford Art Practice courses displayed their imaginative and innovative work at an open studio event on Dec. 3. I was particularly struck by the work created for “ARTSTUDI 163/ARTINST 142: Drawing with Code,” taught by Associate Professor of Art & Art History and Associate Professor by courtesy of Computer Science Camille Utterback. The course explores algorithmic art-making practices, focusing specifically on the visualization tool Processing, a coding language built on Java for artists and designers.

The artworks on display were fresh, and for the most part, simply effective. Using various inputs, the student artists’ unique visualizations allowed their audiences to engage with topics such as representation in STEM, biosensorial information and weather forecasts through new, interesting approaches.

It was a unique experience to walk through the exhibit, where pieces appeared on screens and were projected onto the walls of the Stanford Art Gallery. I was captivated by the amount of effort put into conceptualizing and constructing these different works; some of them were surprisingly playful while others were refined in style, though all were generated from the same algorithmic systems.

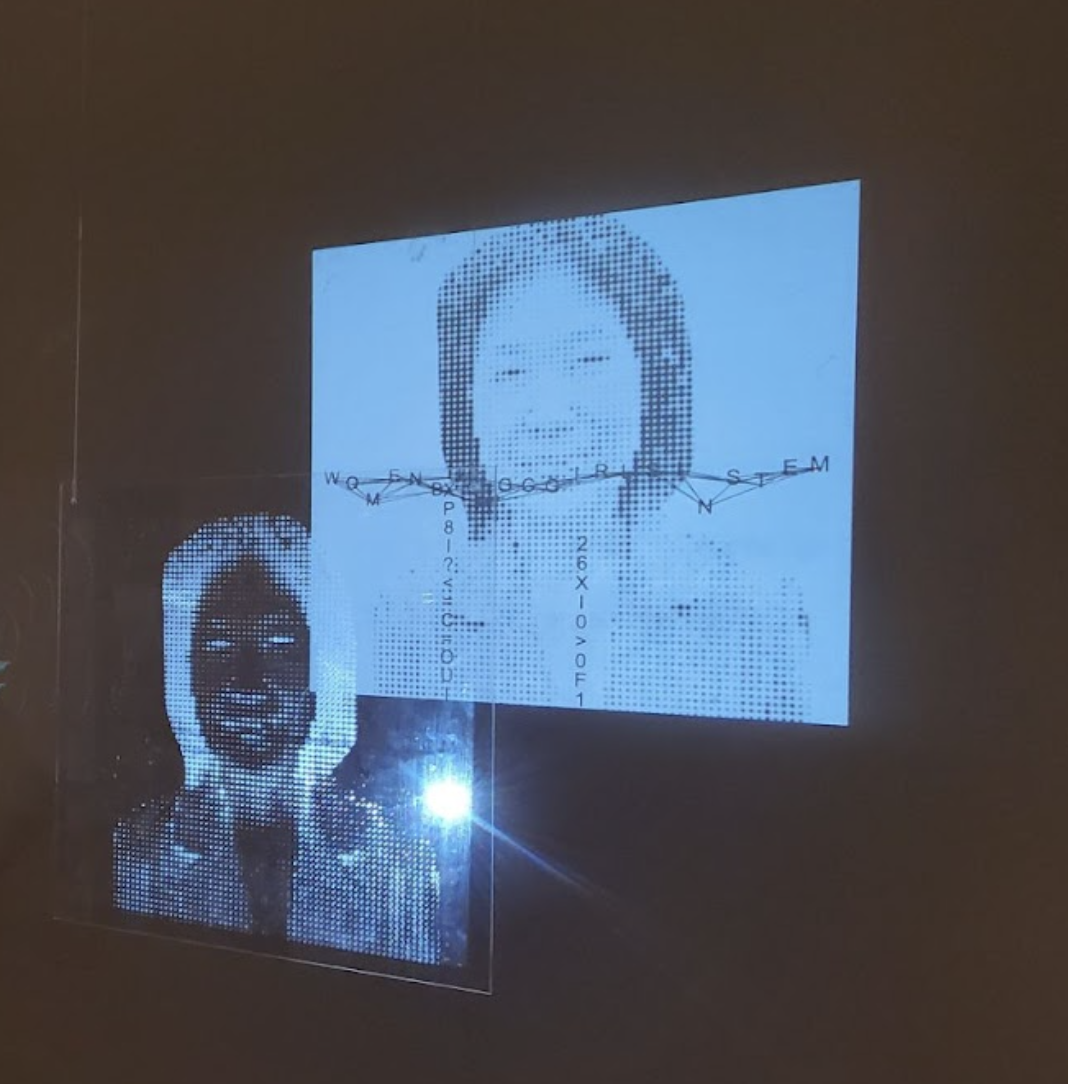

I was most impressed by Amanda Huynh’s ’23 “Women in STEM” (2021). The piece demands attention through its captivating visual and interactive elements. Huynh, who is a computer science major, wanted to explore the feelings of alienation that come with working in a male-dominated industry and cleverly uses coding to do so. The piece starts as an abstract backdrop of various alphabetical characters from English and Chinese. This seemingly random collection of characters materializes from its erratic arrangement into an organized formation, spelling out, “WOMEN BIPOC GIRLS IN STEM.” This gradual shift executed through a sorting algorithm is both clever and aesthetically interesting.

The laser-cut half-tones also formed a portrait of a woman. Huynh told me that the woman pictured was the coder who inspired her to pursue a STEM degree; the camera in front of the projection turns live footage of the audience into live coded video, involving the audience in this petition for progress in the tech field.

Huy Nguyen’s “Embodied Swarm” (2021) similarly stood out for breaking barriers. Coded in the software Unity, the artwork visualizes viewer concentration in real-time. When I entered the open studio exhibit, Nguyen’s biosensing electronics were immediately wrapped around my head. Huy then put clip sensors on each of my ears to track my body’s electricity. I was told to focus on a flame image in front of me, and a live graph reacted to the electrical signals from my brain. The more concentrated I was, the more still the visualizations were; when I was distracted, butterflies danced around in chaos on the screen to reflect my turbulent thinking. Nguyen successfully made important commentary on the ease of distraction with this sci-fi-inspired piece of art.

Perhaps out of fear of being substituted by algorithm-driven artists, as a painter, I was originally skeptical about whether or not algorithmic art production holds the same value as analog creation. However, after attending this open studio, my skepticism has softened. I’ve found that, although algorithmic artwork can appear different and requires different skills, underlying all of the open studio’s pieces was still the human need to communicate and connect.

The works in the class have their own minimalist flair and are precise; they are not what we think of when we think of “traditional” art — like impressionist paintings, which possess the apparent mark-making that is almost like a painters’ handwriting. However, I think algorithmically constructed pieces remain very exciting as emerging forms of art because they allow us to tell varied stories and share data in a creative way.

This is reflected in Harry Moran’s ’23 “Abstracted Atmosphere”, which is a video loop of graphics that tells the time of the day (orange circle moving clockwise), humidity (background color) and sky cover (recursively generated pattern with varying perforation). After a large portion of labor has been transferred to machines, the value of work becomes entangled with the context and the underlying message more than the aesthetic value, alone. In the digital age, art no longer merely competes in photorealism or uses symbols to tangentially provoke a question, but directly lays out information and asks the audience to assign their meanings to them.

The students in Drawing with Code did themselves proud with their vastly different but wholly concise pieces that charmed the audience with wonderment and the possibilities of algorithmic design. But while these pieces are notable on their own, perhaps even more important are the questions that they raise. Even though I was blown away by these innovative student artworks, as a classically trained painter, I was also thrown into a personal existential spiral. Utterback’s class asks: what is the relevance of labour intensiveness in traditional art production, given the context of computer-aided art production methods? Should art become more succinct, or does the verbosity of traditional painting methods evoke something wholly different from the crispness of algorithmic artistic creations? While these questions remain unanswered, I personally believe that art functions first and foremost as a conduit for conversation, an unconventional method of asking questions; the stories should shape the method of storytelling, and if code is the most efficient means for telling a story, then so be it.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective opinions, thoughts and critiques.

This article has been updated to reflect that Amanda Huynh is a member of Stanford’s class of ’23, not ’24. The Daily regrets this error.