On the evening of Jan. 19, cognitive scientist Pietro Scaruffi hosted Stanford’s monthly Leonardo Art Science Evening Rendezvous (LASER) talk, titled “Evolutionary Robotics, Blockchain Art, Metaverse.” Scaruffi was a Visiting Scholar at Stanford from 1995 to 1996, and has been running the LASERs at the University of San Francisco and Stanford University since 2008. This most recent LASER featured lectures from University of Vermont Professor of Computer Science Josh Bongard, Brooklyn-based “immersion artist” Jessica Angel and Stanford Law School CodeX Fellow Eran Kahana. The virtual event, hosted on Zoom, drew over 100 attendees.

Bongard began his lecture by discussing his research interest in robotics as a means of maximizing human potential. Offering an allegory for machine development, Bongard explained how the biological concepts of natural selection and evolution led to the development of diverse organisms, each functioning as a highly effective machine for a specialized task.

“There is someone who has been building adaptive machines, and she’s built trillions and trillions of them,” explained Bongard. “She’s been building them for 3.5 billion years. She is, of course, Mother Nature.”

Bongard then described his efforts to refine his own “evolutionary” or “genetic” algorithm. In short, a computer generates various possible sets of instructions to respond to a given task, and over time, this algorithm is trained to optimize its solution for completing the task, reevaluating its code throughout the process. Bongard’s team of programmers creates tasks while maintaining a set of environmental constraints within the metaverse, and the machines develop in response to these environmental changes.

According to Bongard, this is not the most efficient method, but one that can lead to unexpected discoveries: “[o]ne of the advantages of an evolutionary algorithm is not necessarily that it optimizes behavior. It produces pretty good behavior, and also produces a diversity of behaviors, a diverse set of solutions for us to consider.” In other words, Bongard’s algorithm searches for all the possible combinations of the “robotic neuron,” or the ultimate set of instructions best suited for completing a task.

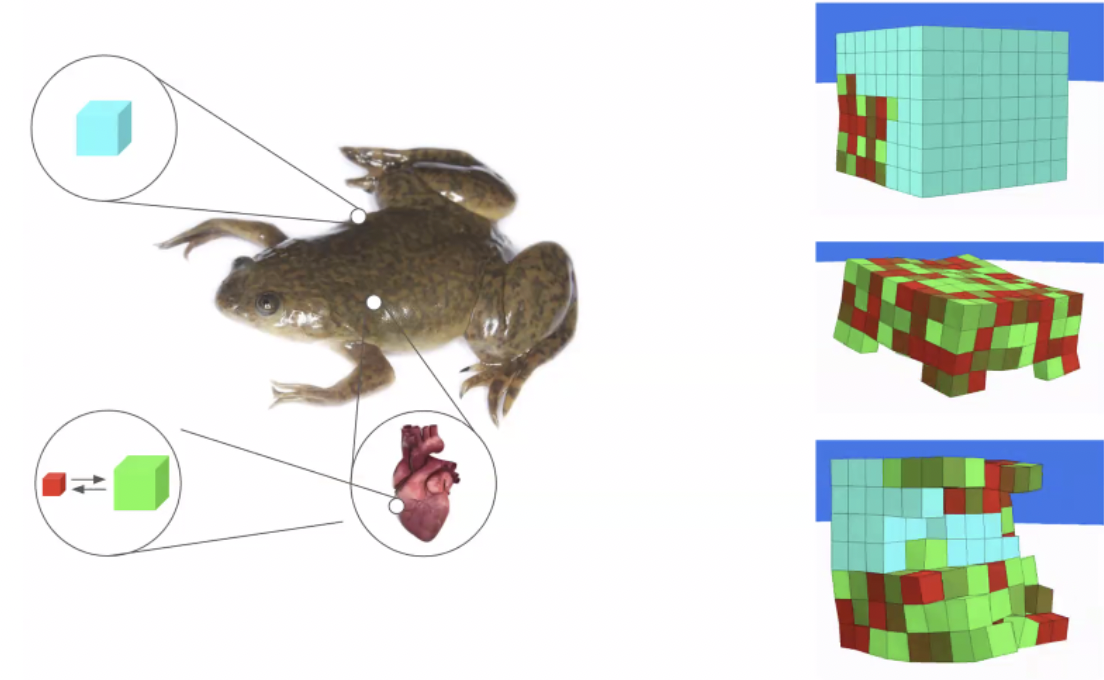

Bongard’s research is done through a physics engine to allow the algorithm’s “virtual brain” to develop before he incorporates it into the mechatronic body that is able to actually execute tasks. This “sim-to-real” transferral increases efficiency in the model. In one of his experiments, Bongard simulated the patches of frog skin and heart tissue using the algorithm, creating a structure that can move between 2 points.

Bongard and Mike Levin — a member of the Living Lab at Tufts University — recently developed frog cells to create a “biobot,” endearingly termed “xenobot” after the frog species Xenopus laevis. This biobot, created from the skin and heart tissues of the frog and the evolutionary algorithm, is capable of motion and represents a major step in the future of nanotechnology.

“The hope is that someday we might be able to build human [biobots] from the patient’s own cells,” Bongard said. He believes these tiny biobots will be capable of performing delicate medical operations inside a patient’s body in the future.

Jessica Angel is a Colombian-born, Brooklyn-based artist pioneering art that uses Blockchain — a data storage structure that keeps track of its history, often used in online financial transactions — to facilitate physical immersion in a site-specific installation. She is interested in how data shapes reality, citing the post-constructionist philosopher Michel Foucault as an influence in her artistic practice.

Angel co-created her first immersive piece, “Inside the Computing Machine,” (2008) with sound designer Gilberto Castillo purely from silkscreen wallpaper. She continued to collaborate with Castillo on “Facing the Hyperstructure” (2017), this time creating immersive art by hand.

Speaking about her relationship with immersive art, Angel explained how she views the world as a dichotomy: “we are inside of space, we can touch it, I call it ‘hard-edge’. But there’s another kind of space, the dynamic space that inhabits the hard-edge space.” Linking this divide between the palpable world and the nonmaterial reality of softwares is what drives her practice.

By creating immersive spaces and murals that occupy site-specific memory, Angel hopes to bridge the gap between the analog and the mechanisms behind the screen. Inspired by Douglas Hofstadter, the American physics researcher who is known for analogy in communication, Angel uses immersive art installations to explore how we as physical beings interact with mechanisms behind the screen.

Angel’s current exhibition, “Voxel Bridge,” was created as part of the ongoing Vancouver Biennale, a site-specific installation under Vancouver’s Cambie Bridge that tells the history of the Kusama blockchain Network. Upon scanning a QR code, virtual projections signal the transition from the purely physical world to that of the Kusama network, which offers popup information via augmented reality (AR) about the historical development of blockchains for curious audiences. Angel created an interactive display to help people see how blockchains can interact with their lives on both physical and digital planes.

Angel attributed her decision not to work fully digitally to her background in traditional painting and drawing. “When you are interested in going to the metaverse and diving into digital spaces,” Angel said, “keeping at least one foot in the physical is absolutely important.”

Angel is also cautious about her use of technology as an artist. “I think artists are getting a little bit tied [to] the technology,” explained Angel. “The technology is so exciting that it just becomes the only thing to explore.”

Indeed, technology and exploration continue to go hand in hand in the modern world. From its early descriptions in acclaimed author Neal Stephenson’s 1992 novel “Snow Crash,” to its more recent interpretations through the avatar-centric game “Second Life” and the controversial rebranding of Big Four tech company Meta, the metaverse has come a long way. In the third and final part of the talk, Stanford Law School CodeX fellow Eran Kahana shed light on the pressing legal considerations of “smarter” technology that remain largely unaddressed.

Kahana believes we need to shift the way we think about AI in order to mitigate the legal ramifications of metaverse crimes. Just like a corporation that can sue and be sued, AI can be considered as an agent under the law — able to perform commercial transactions, execute contracts, monitor performance of contracts, bring legal action, observe rules and evaluate laws.

Naturally, the question thus arises as to why we as humans give AI so much power. According to Kahana, we believe that AI has a fiduciary duty, and thus continually code for “an AI that will be loyal to us as the end-user.”

Kahana remarked that in the future, the judicial processes around the metaverse will have to be in place before the metaverse can fulfill its promise.

“The infrastructure needs to be such that there’s an adjudication to what this is,” Kahana said. “What that would mean is, how did the courts play a part in this? Do we have sufficient mechanisms like the Digital Millennium Copyright Act that protects content related to the internet?”

January’s LASER talk ultimately pondered what it means to exist in a world in which the planes of art, design and technology are significantly intersecting. It prompted attendees to ask how innovations happen, how they will impact us and how to live with these unprecedented technological advances. Most importantly, conversations like these urge us to reflect on what we want our future to look like, and what we want to do about it.