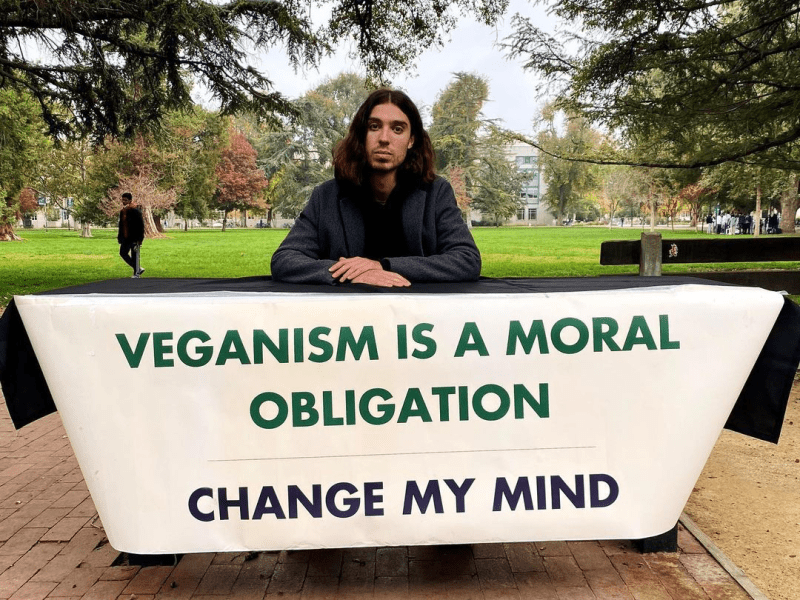

Earthling Ed propped up a table and banner in White Plaza: “VEGANISM IS A MORAL OBLIGATION: CHANGE MY MIND.” Its provocative, all-caps claim drew a small crowd of bike-wheeling students. Ryan Loo ’25 braked to a halt on his way back from class. Kawther Said ’25 and Susan Ahmed ’25, members of Stanford’s People for Animal Welfare (PAW), came soon after Ed first propped up his table. Gerrit Van Zyll — who doesn’t go to Stanford — is a digital marketing analyst whose lunchtime bike ride was interrupted by the sight of Ed, one of his favorite YouTubers.

Earthling Ed was talking to a philosophy major (Ed is not affiliated with the University). Their discussion, ranging from Kant’s ethics to the diets of Inuit peoples, was ripe with academic camaraderie. Eventually, the student stood up, shook Earthling Ed’s hand and revealed she is already vegan.

“I just like to have these kinds of conversations,” she shrugged. Ed’s videographer adjusted his camera on its tripod. Everything would be uploaded online. Except, perhaps, the parts to come.

Ed Winters became Earthling Ed while scrolling through BBC News in 2014. The headline “Hundreds of chickens killed in M62 lorry crash” drew his eye; by the end of the day, he had found a new conviction. He could no longer justify his complicity in the murder of animals. The leftover KFC in his fridge now carved caverns in his conscience.

A year later, Winters, who resembles a vegan Jesus in a Steve Jobs turtleneck, set up his YouTube channel. He began by uploading street interviews in his native United Kingdom, where he spoke to strangers about the ethics of eating animals. Since then, he has co-founded the Official Animal Rights March, a global event which drew 41,000 participants in 2019; released a documentary exposé on U.K. land farming; taught as a guest lecturer at Harvard University; opened nonprofit vegan restaurants in London and Brighton specializing in “tofish and chips”; and written his debut book on veganism, released in January 2022.

But most people find him through YouTube. His most popular video, “Coronavirus is just the start. Something far worse is coming,” has 4.5 million views to date.

This Nov. 18 visit to Stanford University was part of a Northern California tour, sandwiched between stops at UC Berkeley and Davis. Winters’ goal is to get students talking about veganism and, in the most utopic outcome, convince them to make the switch. According to his website, 33,248 people have gone vegan thanks to his content.

The day before was a dream. Belinda Yu, a Bay Area animal-rights activist, could vouch for it. She loves Earthling Ed to the point of seeing him debate at not one but both rival schools. At Berkeley, according to witnesses, Winters faced a resistant but open-minded student who, at the end of their tête-à-tête, declared himself convinced. He was going to go vegan.

“I think many of us are compassionate hearts,” Yu said. “We would make very different choices. It’s the industry … it’s just profit. It’s capitalism.”

But then again, yesterday there was no Leah Waites ’23. As Winters readied himself for his next debate, Waites approached with two handmade posters. They were capitalized. “VEGANISM IS FINE BUT JUDGING PEOPLE FOR NOT BEING RICH IS V V WACKY,” she had written in black Sharpie on posters from the Stanford Bookstore. “I GUARANTEE THESE MF’S UPHOLD ANIMAL & HUMAN OPPRESSION MORE THAN YOUR AVERAGE JOE.”

Waites, a philosophy major decked in transition sunglasses and lugging a water bottle, staked claim to a patch of grass near the bookstore. Winters asked her to sit and speak with him.

“No!” she yelled, raising her signs higher. “I passed your sign earlier, and it was disgusting. And it was racist and classist, and I’m not here for it!”

Waites is a native of rural Alabama. Growing up poor in a food desert, there were times when dinner consisted of taquitos from the Dollar General, she said. When she first tried the vegan options at the Stanford dining halls, she said, she was shocked to find vegan food could taste good. There just wasn’t any where she grew up.

Earlier that day, Waites, who is a white woman, opened Instagram to see several people of color posting about how Winters sign is offensive to Indigenous and African cultures that prepare meat in a respectful and sustainable manner. (She was not sure she remembered the specific details of the posts.) She called her parents, told them what she was going to do and went to buy her posters.

“They worry about me,” she told me. “It’s just me up against a lot of people all the time.” Waites explained that these confrontations are not out of the ordinary for her. They were especially common back home, she said.

In White Plaza, Waites told Winters that being vegan would take a disproportionate toll on her as a poor person. But Winters challenged this — why can’t she be vegan at Stanford? There are abundant options at the dining hall.

“I could be vegan,” she said.

“So, why aren’t you?”

“Because it’s not something that I feel I need to spend my time doing. Because I do a lot of other moral things that help humans more.”

Waites’s volume reached a level that drew stares. A middle-aged woman walking her dog stood and listened by the Claw. Waites was criticizing Winters, heatedly, for spending his time talking about veganism when “there are workers at these dining halls who are being exploited right now, actual people of color.” He tried to respond and was cut off.

“You’re a white guy,” Waites said. “I can interrupt you.”

“And you’re a white woman.”

“Well, you’re copping out of the fact I’m saying that you’re racist, and you’re not saying you’re not a racist. You’re saying, how do you? That’s not an answer, right? Apparently because you won’t even say you aren’t.”

Ed turned to the audience. “Anyone else here think I’m a racist?” he said. “What about the people of color who aren’t white? Why is it only the white woman who thinks I’m a racist?”

The audience was silent. More students filtered into the crowd. The decibel of raised voices had proved magnetic.

“You’re not worth it,” Waites told Winters, “but I hope people read these signs.” She faced the gathered students, now almost 20 of them. Several iPhones had risen to film her.

“Isn’t it funny to hear him talk?” she said to the cameras.

“It’s good to hear him talk,” a voice in the crowd said.

Then Winters vied for the onlookers’ sympathy.

“Who would have thought that asking someone not to kill an animal could be such a divisive scenario? But it enrages people. It makes them a racist because they say, ‘Hey, if you don’t have the moot to cut the throat of an animal…’”

“Awww, did your sign say that?” Waites said.

Sideways glances in the audience. Ed looked lost, like he had been dropped into an alternate reality.

“The only place I’ve had people scream at me is here!”

“I’m glad! I’m glad people here have the guts!”

A beat of silence until, finally, Waites said, “I’d like you to stop talking to me,” and then she turned away.

For a person in the crowd, this was an opening to pose a question. She asked Waites why she felt she could speak on behalf of people of color.

“Why should the people who are affected most have to fight for things?” Waites responded. “If I have free time as a white woman to fight for shit because it’s easier for me to come here and stand up for people, shouldn’t I fucking be doing that?”

“You’re just making them look bad,” the crowd member said.

“I’m making people of color look bad?”

“Yes, you are, because you’re saying shit that doesn’t make any fucking sense.”

“Okay. That’s one of the strangest arguments I’ve ever —”

“You are very strange. You’re a very strange person,” the crowd member deadpanned. “You can’t just throw around the word ‘racist.’ … How is he racist for saying to go vegan?”

For the first time, Waites turned quiet and still.

“Okay. Then, we see the world too differently for me to argue with you about this. I’m sorry.”

Waites turned on a Bluetooth speaker. Pop music swept into the scene, finding Earthling Ed with his palms up in disbelief, wearing a pinched look that appeared to be saying, Forgive them, for they know not what they do. Waites raised her signs above her head and swayed to the songs.

The crowd splintered. Friends turned to friends to discuss.

“I understand the desire to want to be an ally for marginalized voices,” Loo said. “But I do feel as though it’s in poor taste to be unnecessarily hostile about it while also saying, ‘Oh, I’m doing this for this group of people.’”

Celeste Jupiter ’22, a senior studying human biology, pursed her lips at Winters’s behavior: “His consistent reference to ‘what do you people of color think today?’ was like … I’m not gonna be your representative for people of color today.”

A new student sat at the table to debate Winters. He introduced himself as a libertarian. Their conversation was barely audible, its nuances washed away by Waites’s music only feet away. She remained, signs up, rooted.

The next day, Winters would go to UC Davis. He anticipated negative reactions to his sign — Davis is a big agricultural school. It hosts a poultry judging competition every year.

But here, in Palo Alto, the sun was inching to leave. Some 20 minutes later, Waites folded her posters under her arms. She told Winters he did not have permission to post the footage of her online.

“It was nice to meet you,” Winters called out, turning from his conversation with the libertarian, to which Waites replied — her back shrinking from the foreground — “No.”

As the videographer packed his tripod and the crowd dwindled to zero, White Plaza was left in a virulent whiplash of emotional reactivity, a dissonant mood of unconsciousness. The trees swallowed the sun. All that was left of Earthling Ed were four indentations in the grass where his table stood moments ago. The teachers left to learn from themselves, and White Plaza was left alone. Students biked like newsboys from corner to corner.

This article has been updated to reflect that an unnamed member of the crowd was speaking to Leah Waites rather than Kawther Said, to whom some quotations were originally misattributed. The Daily regrets this error.