STUDENT LIFE

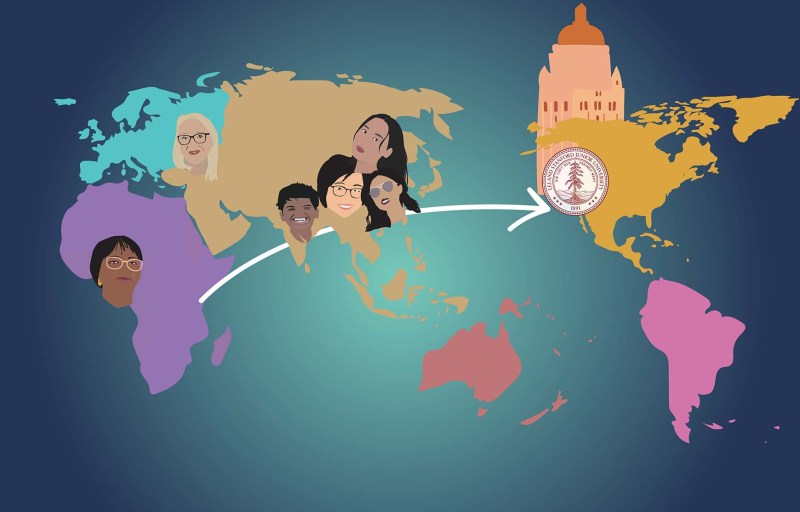

Far from home: Stories from Stanford’s International community

By Enkhjin Munkhbayar

During the three years of the Nigerian Civil War in 1970, Gladys Ajaelo did not go to school. Even after her tribe’s defeat, Ajaelo, along with many other Igbo tribe people, could not afford education in Nigeria due to the devastation of the war. In hopes of catching up on her disrupted education, Ajaelo decided to leave her home country and come to the United States.

“The U.S. was very sympathetic toward the Igbo people,” Ajaelo said. “It offered us the means to go there and study.”

With hopes of returning to Nigeria to teach English, Ajaelo chose to study English at the University of California, Berkeley as an undergraduate student. Now, a mother of four and a grandmother of five, Ajaelo teaches Igbo language at Stanford as a lecturer.

For many international students and faculty like Ajaelo, the process of transitioning to a new country is also a journey of discovery. From learning another language to experiencing a different culture, many have to quickly adapt to their new environment and navigate through colliding ideas, opposite values and traditions that differ from their own.

Nomunzul Battulga ’23 hopes to create a Mongolian Student Association. Ravichandra Tadigadapa ’23 grapples with race. Feiyang Kuang ’25 connects to her culture through literature and the Dragon Boat club. Yuliya Ilchuk and Gladys Ajaelo teach their cultures in Stanford classrooms.

Before teaching, Ajaelo was getting used to the new culture as an undergraduate in the Bay Area. After moving to the U.S., one particular word began to take on a new meaning for Ajaelo: race.

“In Nigeria, everybody is Black. Everybody is the same,” she explained. “Then, when I came to a foreign country, I suddenly began to realize that I’m different.”

Curious about the concept of race, she began to take courses on ethnic studies, which she said was not an option in colonial education. What started as a curiosity soon turned into a passion, which inspired her to teach Igbo language and culture to both Igbo students who were born abroad and foreigners who are not affiliated with Igbo culture.

Ajaelo emphasized the importance of ethnic studies in educational institutions as a means of growth and development for students. When people learn about other cultures, “they become people who are very tolerant of others who are different from them,” she said.

Like Ajaelo, Yuliya Ilchuk — assistant professor and undergraduate studies director of Slavic languages and literatures — dedicates her time to teaching students about her culture.

When Ukraine declared independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Ilchuk was an undergraduate student. As a Russian speaker, the transitional period that followed was a challenge for her — amid the chaos of economic and political debilitation, she had to learn a new language.

“It was a very difficult transitional period in the history of my country,” she remembered. “I wanted not just better economic conditions, but a place where I could, as a woman, make a career as a scholar.”

This desire inspired her to apply for a Ph.D. program in the U.S. While she received her bachelor’s and master’s degree in her home country of Ukraine, she came to the U.S. in 1999 to pursue a Ph.D. in Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Southern California (USC).

After her arrival, Ilchuk remembers regularly studying in the library from 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. and staying in pajamas throughout the weekends to complete assignments. While the academic load was significantly more than she had experienced in Ukraine, Ilchuk liked the flexible academic structure within USC. “Being responsible for my own education was the main difference,” she recounted.

Though adjusting to her new home was not easy, Ilchuk had Ukrainian friends in the U.S. to rely on. “Just seeing my fellow Ukrainian women who came from poverty and became very successful professionals motivated me as well to do my best,” she said. As a Christian, Ilchuk also goes to the Russian Orthodox Church to feel uplifted and connected with her culture. She added that she tries to teach students about non-academic subjects, such as church iconography and different recipes from Russian or Ukrainian cuisine.

Similar to international faculty, international students must learn to navigate their new environment and find ways to feel at home away from home.

For Ravichandra Tadigadapa ’22 M.A. ’23, an international coterminal student from India pursuing a bachelor’s in economics and a master’s in international policy, the new environment forced him to grapple with a concept that was previously unknown to him: his identity.

Tadigadapa came to the U.S. in 2017. Looking back on his first year at Stanford that year, he remembered excessively watching and listening to American TV shows and music to learn about pop culture. At the same time, he grappled with the realization that he had a unique identity that he aligned with and that others associated him with.

“I didn’t think of myself as being a certain type of person,” he said. “And I come to the U.S., and not only do I identify with a certain race, but also everyone around me identifies with race as well. There was sort of a shifting moment in my understanding of identity.”

He became keenly aware of his identity amid the COVID-19 pandemic. The Trump administration’s rescinded proposal surrounding international students’ status during the pandemic, and its rule that limited their entry and period of stay in the U.S. were emblematic of something else to Tadigadapa.

“The decisions revealed to me that, in a way, my options are much more restricted than average American students,” he said. He added that what he saw as empowering and liberating narratives prevalent at Stanford are “often catered to the American student population” rather than international students.

Tadigadapa decided to take a gap year during the pandemic to take time to reflect on his background and think about his post-graduation plans. Now, he said he feels more aware of the role his international background plays in his life at Stanford and beyond.

Tadigadapa is eagerly anticipating his graduation. “I can see graduation being very rewarding because I know that I came to a foreign country, started afresh, navigated life at Stanford by myself, and at the end of it, achieved something,” he said.

Nomunzul Battulga is an international student from Mongolia, studying civil and environmental engineering. Her interest in sustainability stems from the issues present in her home country. From seeing disparities in infant mortality rates in Mongolia due to air pollution versus rates in other countries with accessible clean air, Battulga knew she wanted to make a change. She believes “there is a way for humans to coexist with human-made worlds and environments without inflicting damage,” and she hopes to create structures and work on projects that enable coexistence as a future engineer.

Although Battulga is a junior, she has on campus for only a year now. Due to the pandemic, she spent her sophomore year in Mongolia, attending online classes that started at 3 a.m. because of the time difference.

Battulga’s time at Stanford, however, is full of fond memories. For example, she recounted cooking traditional Mongolian food with one of the dining hall chefs for the Lunar New Year celebration. “Lunar New Year is one of the traditions that is so interconnected with who I am. Even though I didn’t have my family around to celebrate with me at that time, I still wanted to celebrate it to connect with my culture,” Battulga added.

Battulga hopes to create a Mongolian Student Association at Stanford, as “it would be great to leave behind a community” for incoming first-year students before she graduates.

One of the newest members of the international community at Stanford is Feiyang Kuang ’25, who came to the U.S. from China just four months ago. Like Battulga, Kuang likes to connect with her culture on campus. For her, this occurs through Chinese literature and the Dragon Boat club.

Since coming to Stanford, Kuang has been exploring a wide range of courses and the East Asia Library. She said she is thankful that Stanford has a “general flexible atmosphere around exploring different opportunities both academically and personally.”

Kuang described her adjustment process as feeling unreal because it is so instantaneous: “It’s never a process of easing into another culture,” she explained.

Though the transition process can feel fast, Kuang advised international students to remember that it will slow down over time.

“It is easy to believe the inertia of being subjected to cultural shock, having a hard time adjusting to everything and feeling overwhelmed. When you’re in the middle of it, it is very tempting to think that this inertia would carry on and extend unbounded in the future,” she said. “But do know that it changes, and when you’re out of it, you won’t feel that way.”

At Stanford, there are many resources and groups, such as the International Undergraduate Community (IUC), that provide support for the international population. The IUC aims to bring global and domestic students together through hosting events, such as dinners and cultural performances, and launching programs that celebrate diversity.

The IUC also launched its SibFam program last year. “The program is meant to create a small family for underclassmen who might not have found a tight international community or who just want to get to know more people and have someone to ask for advice,” said WenXin Dong ’23, an international student from China and the co-president of the IUC. The IUC plans to launch this academic year’s SibFam program during the winter quarter.

Though all students did not have to move to another country for college, Kuang sees common grounds in their efforts to navigate their new environment at Stanford.

“International or not international, we are all going through the college process for the first time, experimenting with how we want to interact with people as we become fresh adults,” she said. “I like how we are all just stumbling around trying different things and bumping into each other in the process.”