Steve Schneider was a pioneer.

“He was the one that was sounding the alarm for climate change, back in the ’70s. That was a long, long time ago,” said Terry Root, Schneider’s wife and senior fellow emerita at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

Schneider’s outspoken climate advocacy came at a time when “global warming” was a concept foreign to the public imagination. In fact, the first paper Schneider ever published projected global cooling.

“And then he went back and looked at it and he said, ‘Oh my God. No, I’m wrong,’” said Root.

This year marks the 10-year anniversary of the Stephen H. Schneider Memorial Lecture, the largest environmental lecture on the Stanford campus, which will take place on Wednesday. Organized by Students for a Sustainable Stanford (SSS) in collaboration with the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, the event features speakers representing the vanguard of innovation, activism and leadership in the field of environmentalism.

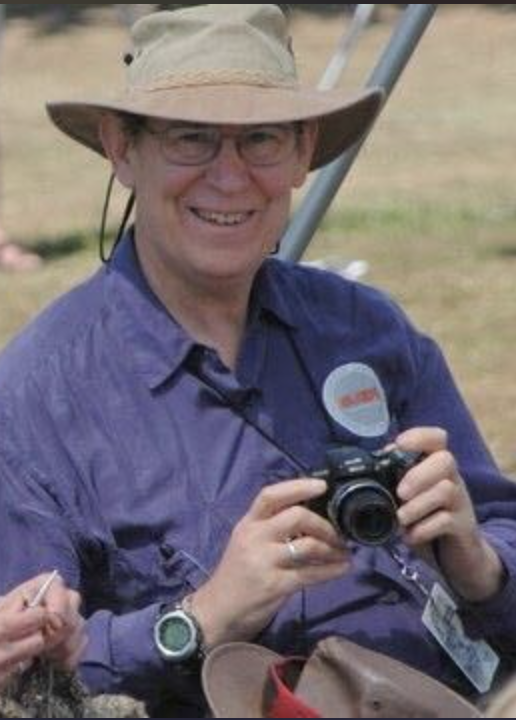

The lecture is held annually in memory of Stephen H. Schneider, the globally-renowned climate scientist and Stanford professor who passed away in 2010. After joining the University in 1992, Schneider was instrumental in the formation of Stanford’s Earth Systems programming, as well as the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, the University’s hub for interdisciplinary environmental and sustainability research.

Schneider’s pioneering work earned him a MacArthur Fellowship “Genius Grant” in 1992, as well as a share in the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize for his role as a lead researcher on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

“Climate change is the existential threat to the planet right now,” said Jeff Koseff, founding co-director of the Woods Institute and a close personal friend of the late Schneider. “So I think it’s important to remind ourselves of the challenge that lies ahead, and I think the lecture serves as a clarion call to action.”

Starting the lecture series

Upon Schneider’s passing, a memorial fund was established through the Woods Institute. Root and Koseff discussed how to best use the funds to honor Schneider’s legacy, ultimately deciding on a lecture series.

“One of the huge barriers in addressing climate change is a communication problem,” said Meghan Shea ’17, organizer of the fourth and fifth Schneider Lectures in 2016 and 2017. “It’s figuring out, how do we get the most people to care about this topic that needs as many people thinking about it as possible?”

Schneider believed unwaveringly in “the power of effective communication,” according to Koseff. He was “the type of person who could talk to anybody,” from second graders to senators, Root said. The lecture series embodies Schneider’s spirit of making environmental discourse accessible to wide audiences.

“The lectureship is probably the very least we could do to honor his memory,” Koseff said. “I’m sure Steve would approve.”

For the inaugural lecture in 2013, Root wanted former Vice President Al Gore, who was also Schenider’s personal friend, to speak. Root contacted Gore’s office, assuming weeks would pass before she would hear back.

“I hung up the phone and literally 10 minutes later, Al Gore calls me on the phone and says, ‘I’ll be there. What do you want me to say? When do you want me there? I will be there,’” Root said.

While the initial lecture in 2013 was assembled largely by the Woods Institute and Root herself, she “really wanted to have it be student-pushed and student-run,” because “student involvement is important for it to actually be meaningful to the students.”

“If you own what you’re learning, you take it to heart,” Root said.

A decade of lectures

SSS took up the mantle, assuming primary organizing responsibility of the Schneider Lecture. According to Tanvi Dutta Gupta ’23, one of the three co-leads for this year’s lecture, the endeavor entails everything from selecting speakers to negotiating contracts and honoraria, booking event spaces, securing co-sponsors and managing publicity.

“It was a really, really big logistical undertaking, and definitely the largest event that I’d managed as an undergrad,” remarked Shea.

Megan Rogers ’23, who organized the ninth Schneider Lecture in 2021, said that the event’s evolution over the past decade reflects Stanford students’ changing interaction with climate change and policy.

Historically, the environmental movement “was a very predominantly white, affluent, heteronormative space, just based off of who was allowed to have access to those spaces and who had the time and money to worry about climate change,” Rogers said.

But in recent years, Rogers witnessed the Schneider Lecture “go a little bit more the grassroots route,” placing more emphasis on environmental justice and intersectionality.

For those behind the scenes, the Schneider Lecture has also fostered a long-lasting community.

“I’ve gone to a lot of them, which has been really fun,” said Caroline Spears ’17, who organized the third Schneider Lecture in 2015. “Friends of mine, if we’re all in the area, we’ll all drive down to Stanford and go to the Schneider Lecture every year.”

Despite the Lecture’s conviction toward forward-thinking environmental action, some boundaries remain too entrenched to transgress. In 2015, the Woods Institute vetoed the selected guest, environmentalist and author Bill McKibben, who in 2012 spearheaded a nationwide student campaign to demand institutional divestment from fossil fuel stock.

Seven years later, divestment remains an area of controversy, even among Stanford’s sustainability-centered institutions.

This year’s Schneider Lecture, which will take place on Wednesday, will feature Mustafa Santiago Ali, a world-renowned environmental justice activist, founder of the Hip-Hop Caucus and Vice President of Environmental Justice, Climate and Community Revitalization for the National Wildlife Federation. After working at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for 24 years, Ali resigned in 2017 in protest of the Trump administration’s plans to dismantle the agency’s Office of Environmental Justice. “Dr. Santiago Ali will teach us a lot about what it means to do climate action and what it means to practice environmental justice,” said Dutta Gupta.

“I miss Steve. Every day,” Root said tearfully, referring back to Schneider. “He was the most wonderful man. He was my soulmate. He was everything.”

“He tried to save the world.”

This article has been corrected to accurately reflect Tanvi Dutta Gupta’s full name. A previous version of this article identified her as “Tanvi Gupta.” The Daily regrets this error.