There is a local legend in Tonga that refers to a devastating “peau kula,” or a red wave, that once overtook the entire island. Tonga natives would have been content leaving the peau kula to myth — an ancient cautionary tale passed down the generations.

But when Esiteli Hafoka, a Tongan American religious studies Ph.D. student, heard what sounded like a “huge bomb going off” through her uncle’s Facebook livestream from Tonga on Jan. 15, the legend felt all too real. The roar of the Tonga volcanic eruption and the tsunami that followed echoed through her feed until, a few hours later, the posts stopped coming. Hafoka wouldn’t hear a peep from Tonga for another five days.

Everybody was on edge, Hafoka said. “I was most worried about my family in Ha‘apai, because it’s so close to the eruption.”

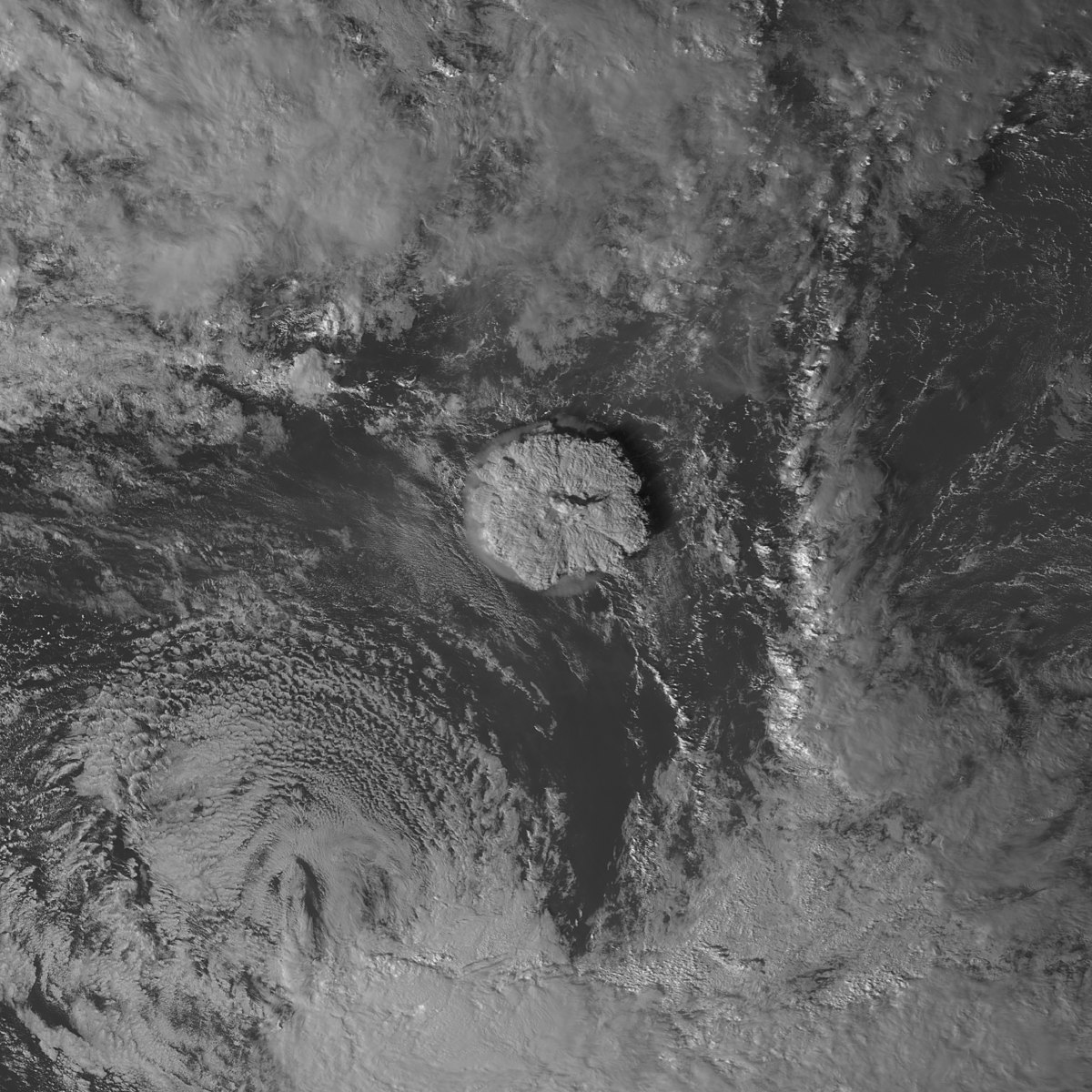

The underwater volcano erupted 40 miles north of Tonga’s main island, Tongatapu, triggering a tsunami that destroyed all homes on one of Tonga’s 36 inhabited islands and killed three Tongans. Tsunami warnings rippled as far as the Bay Area.

Tonga is no stranger to natural disasters — since 2015, the country has weathered three category-five cyclones. But the eruption in Tonga was a once-in-a-millennium event, said Shane Cronin, a professor in volcanology at the University of Auckland, to CNN.

“It takes roughly 900-1,000 years for the Hunga volcano to fill up with magma, which cools and starts to crystallize, producing large amounts of gas pressure inside the magma,” Cronin said. “As gases start to build up pressure, the magma becomes unstable. Think of it like putting too many bubbles into a champagne bottle — eventually, the bottle will break.”

For most Stanford students, satellite images of the plume made for just another sensational headline. But for Stanford’s Tongan diaspora, the eruption meant juggling school and silence from loved ones while attending a university largely unaffected by the issue.

Kivalu Ramanlal ’22, a Tongan native, watched as the issue was all but absent from campus conversation, save for emails about relief efforts from Stanford’s Pacific Islander community. Social media posts about the disaster emphasized the geological wonder of the eruption, rather than the safety of its survivors, including Ramanlal’s uncle, cousins and relatives in Haʻapai.

“I’m not sure how they’re doing,” said Ramanlal. “But I think I would have heard something if they’re not okay.”

Even on the national scale, it seemed to Ramanlal that stories about the eruption barely lasted one news cycle. Adding insult to injury, “many social media posts were of people claiming that they didn’t even know that Tonga existed until minutes ago,” Ramanlal said.

“I think it’s just because, in America, at least, nobody really knows about Tonga,” Ramanlal said.

Hafoka, on the other hand, was impressed by the increased awareness, taking note as distant colleagues expressed support, or strangers stopped her husband at Disney World to comment on his Tonga shirt.

“Because of sensationalized media reports, there’s now interest in helping Tonga,” Hafoka said. “But I think there should be a little bit more media attention towards the relief efforts.”

On Feb. 5, Hui O Na Moku — Stanford’s Pacific Islander student organization — hosted a supply drive to support victims of the recent volcanic eruptions in Tonga. Their table at White Plaza collected water and first aid donations for the thousands who lost access to clean water and basic medical supplies. Their drive was part of a local effort spearheaded by Bay Area restaurant Tokemoana Foods, in Redwood City, to ship donations directly to Tonga.

Others are rallying to ship medical supplies to the Pacific island nation, including two tons of supplies donated by Kaiser Permanente at the ‘Anamatangi Polynesian Voices warehouse in Mountain View.

Despite relief efforts in the area, stress levels remain high for the Tongan community on campus as ashfall spoils food and water sources in the nation and poor satellite signals limit contact.

“A lot of times it’s just luck, whether or not your call gets through,” Ramanlal said on Feb. 16. “So, I actually haven’t spoken personally with anyone in Tonga.” Hafoka worries for her uncle, who relies on crops which may be affected by the ashfall.

With the price of bottled water increasing in Tonga, Tongan communities across the country are growing concerned about whether relief efforts will be enough.

“The situation makes me feel so privileged to have access to drinking water,” said Sela Fifita, a Tongan woman living in Hawai’i whose mother could hear the blast from Fiji. “In Tonga, there’s always rain and therefore, always water. I never thought that this would happen to all of us.”