“ONE DAY, when all our people were gone out to their works as usual, and only I and my dear sister were left to mind the house, two men and a woman got over our walls, and in a moment seized us both; and, without giving us time to cry out, or make resistance, they stopped our mouths, tied our hands, and ran off with us into the nearest wood.” — Olaudah Equiano

Imagine this:

One day, you are in your home with your family, peacefully existing and enjoying life. The next, you are kidnapped, shackled up and loaded on a ship, to who knows where across the sea. You’re packed like a sardine on a ship with people you don’t know. They force you down on your back, next to rows and rows and rows of others and put a box under you for you to pee and poop and do whatever else in.

This happens for weeks and weeks and weeks.

You don’t know where you’re going — or if you’re going anywhere — and you don’t know what people are saying because you don’t speak their language, even though their skin shines a similar shade that yours does. The conditions are horrid. Some people throw themselves overboard. Others die and are thrown aboard. Somehow, you survive, despite it all.

You arrive at a foreign land, and the rest of your life is no longer yours.

“I FELT very sorry when I saw the other slaves come up from the hold of the ship daily, into the air, and heard their heartrending cries of anguish; fathers & mothers longing for their homes and children, and often would neither eat nor drink, and were so strictly watched and held in such rigid confinement. We reached Kingston, Jamaica safely, and here the sale of the slaves began.” — Akeiso / Florence Hall

Not only are your 12 to 15 million fellow West Africans enslaved, but so are their sons and daughters and their sons and daughters and their sons and daughters and their sons and daughters, for eight or so generations, even though the people who looked like you and eventually became you have been here since 1619.

Generations later, the sons and daughters of the sons and daughters of the sons and daughters of the people who enslaved you claim that the place where they enslaved you is a place of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

You hope at a better time, your descendants will not forget you and use that to become great in a way that you never could. One day, maybe the sons and daughters of your sons or daughters will be free. But that time is not now.

– – –

These quotes are from an exhibit I saw at Oxford about slavery and revolution. It was an old exhibit about to be archived and its objects put away, but I couldn’t stop looking and reading. I felt so sad and annoyed. I wondered — what did my enslaved ancestors go through? How do I reconcile with the pain they endured, and how is that pain not adequately addressed in any education system I know?

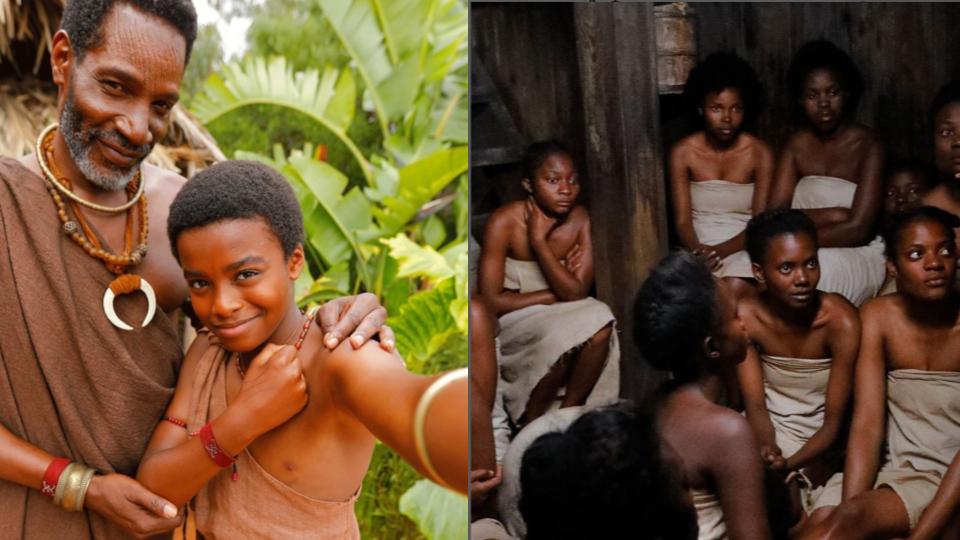

I still don’t know how to piece it all together in my head. But little by little, I am figuring it out. I also have hope that these stories will continue to be shared — the pain, but also the little joys and acts of resilience contained within that. One example that gives me hope is on the Instagram page @equiano.stories. It tells the story of Olaudah Equiano (the source of the first quote) as a young boy through an Instagram film. It answers the question:

“What would it be like if a kid being taken into slavery had Instagram?”

I know that may sound grim, but it’s surprisingly light-hearted and appropriately harrowing at the same time. The film, told through a series of highlighted Instagram stories, is a vivid reimagining of his life pre-enslavement — the colorful culture of his Igbo village, sibling dynamics as a normal kid, the looming fear of capture and the prophetic Dibia. It also covers Olaudah’s capture and enslavement on the boat. In later highlights, the film takes on a more serious air after Equiano is captured; nonetheless, there are inspiring moments and tales of humor, solace and resistance.

We learn of how Olaudah had “boat brothers and sisters” even on the confines of the ship, how the enslaved people sang and joked despite the horrors of it all, how Olaudah thought that the portrait of the “white” man was alive and secretly watching him. We also see much more disturbing things — how a woman was muzzled and forced to eat after resisting, how people who fought back and died of disease were thrown overboard and how families were separated, never to reunite again. We see depictions of incidents which millions of Africans bore witness to, told through the lens of this bright, young boy.

After watching the Instagram film, I immediately sent it to my cousins, aunts and some friends. I realized the importance of what I was watching. Just like the Oxford exhibit, I couldn’t stop looking and reading, but for some very different reasons. While watching the story, sometimes I couldn’t help but smile and sigh and think, aren’t we resilient? Imagine that.

Years and years into the future, decades and decades, centuries and centuries, your people acknowledge your struggles and greatnesses. They use that information to empower themselves and embrace the Queens and Kings and Royalty they truly are. They claim autonomy; their stories are told through their voices. You would be proud.

Imagine that.

About the series:

Normally, I have written Daily articles about my infatuation with Stanford (e.g., 10 Things Stanford Feels Like Beside a School, 10 Unique Moments I realized I was here, 23 things I Missed About Stanford). And those are really fun to write, to share and express my appreciation of being at a school I love very much. But with this “Afropreciation” series, my goal is to explore my experiences and thoughts about the world from the ‘Afrocentric’ view that I can offer — one that centers my experiences as a Sierra Leonean-American girl — and to put them into conversation in hopes of understanding more about the world around me. I acknowledge that I am one perspective, and I’d love to hear what other people from a wide array of perspectives — be it from the African diaspora or otherwise — think about these issues and/or my points of view on them. Feel free to email me to chat. I am always open to learning, explaining and elaborating on things. Any resources are also appreciated. Thanks for reading.