As the first speaker of “Faces of Community” walked up the podium in Frost Amphitheater, the screen over her head immediately caught the audience’s attention. During this convocation of the Stanford Class of 2025 and transfer students, the colorfully illustrated texts like “Content warning: sexual assault, violence” on the LED screen became one of the first impressions that Stanford left on us. For some, this represented Stanford’s protection of those who are experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), while I viewed it as the institution’s meticulous effort to steer the line of political correctness in a way that does not offer concrete assistance to those in need.

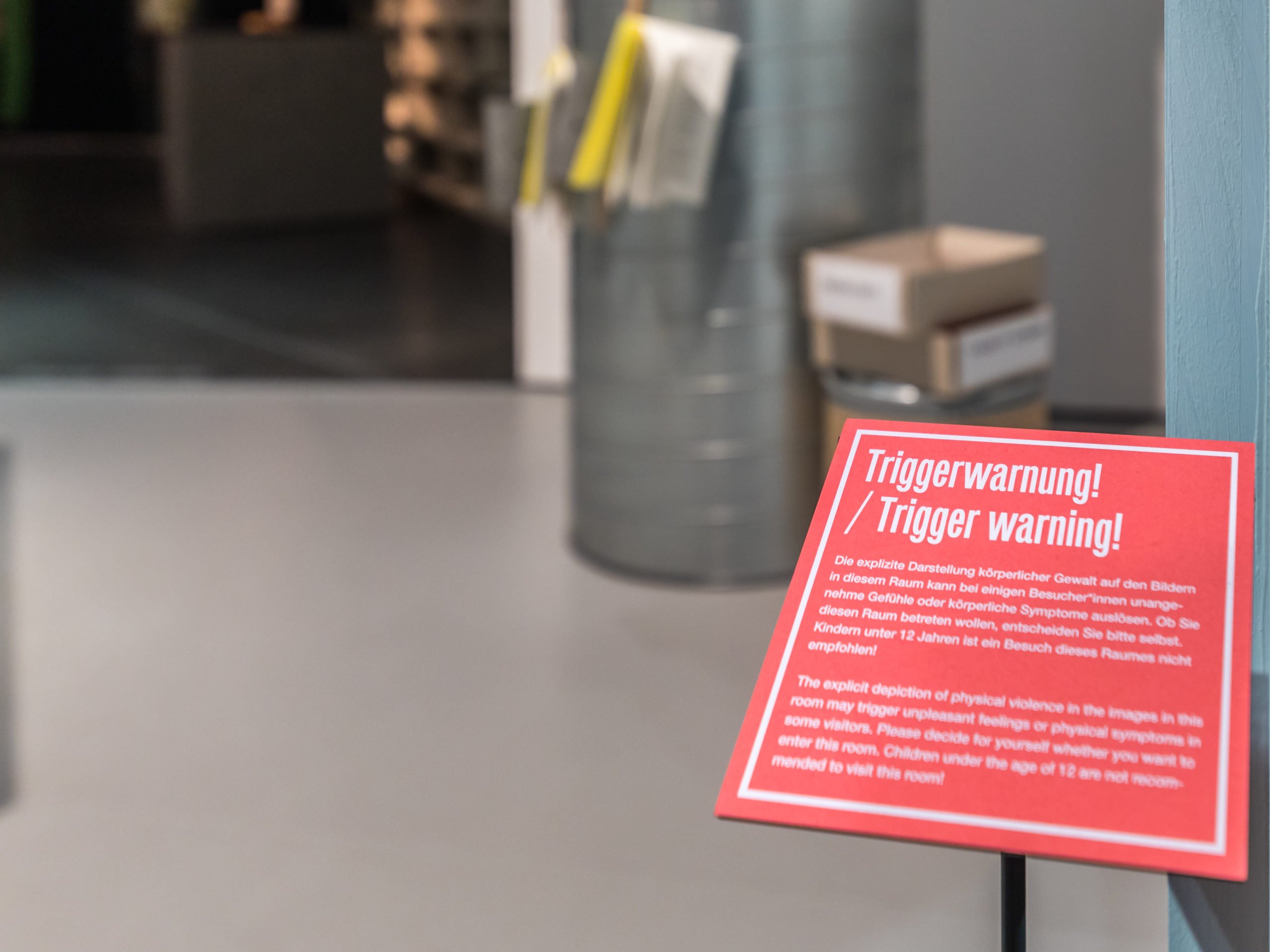

The concept of a trigger warning originated from the psychiatric literature to describe the process by which thoughts and images can bring traumatic events back to life for those experiencing PTSD, unleashing re-experiencing symptoms such as intense fear. With the rise of the focus on mental health across the country in the last few years, “care culture” — an environment in which those in a position of power are responsible for protecting the mental health of others — has surged on college campuses and the art community, two highly liberal-minded contexts.

These changes, however, are often initiated from the bottom-up: from students pressuring professors and audience pressuring artists. According to a National Coalition Against Censorship survey, more than 34% of the surveyed university-level educators reported that their students pushed for the use of trigger warnings or made complaints about lack thereof, while more than half believe the warnings to be detrimental to classroom dynamics and/or academic freedom. Directors of artistic production also complained of having to spoil elements of their work but eventually gave in to the use of warnings out of consideration of the wishes of their patrons.

For professors, including a content warning often entails merely adding a line or two about an assigned reading or film on the syllabus. The artist, however, has much more at stake in revealing details regarding their work. As argued by twentieth-century literary critic Viktor Shklovsky, one of the most important characteristics of art is its ability to unveil reality to the audience by “making-strange” day-to-day details, the ability of which would be significantly impaired by alerting the audience of what will happen ahead of time. While many argue that a good piece of art has the ability to surprise the audience despite the warnings, the popularized “care culture” norms in the consumer-driven art world means that those in the creative industry often need to present their message in a way that does not upset the audience. That audience can in turn use the public attention surrounding mental health to block out the content that they do not want to see. These norms tie the hands of the artists, who for centuries have been at the frontline of protesting societal oppression, like that of minorities.

In the arts scene at Stanford, a liberal educational institution, the use of content warnings is no less prevalent. The event description of Asian American Theater Project’s December production of Among the Dead — which tells the story of the identity quest of Ana Woods, born of an American soldier and a Korean comfort woman during World War II — alerted the audience of “war violence, sexual violence, and M**der”; the refusal to fully write out the word “murder” is reminiscent of censorship.

Moreover, trigger warnings alone are often insufficient in helping those experiencing PTSD process their trauma. Studies have shown that they do not alleviate trauma-survivors’ negative emotional response to certain materials and can even result in their greater anxiety. Their usage has persisted in the art world regardless. In effect, in pressuring artists to adopt the warnings, cultural authorities are shifting their responsibility to provide resources beneficial to the mental health of the citizens to the artists, creating an unnecessary burden on the latter and oftentimes limiting their expression.

“Just like we do not ask hospitals and doctors to perform in purpose-built environments for learning, entertainment, and social change, we should not demand that theaters and artists should become arbiters of what is triggering or potentially traumatic to an infinite number of possible audience members,” argued theater and performance studies professor Samer al-Saber in an email to The Daily. In a lecture to the students of ITALIC 91, Professor al-Saber voiced his opinion that in entering the theater the audience signs a contract with the artists to experience the production fully.

To protect both those processing trauma and the artists’ right to make social impacts by impressing the audience, the path that Stanford and other institutions should take is to better provide mental health resources to the population and support artists’ free expression. Even so, as expressed by Professor al-Saber, “Given the size of the task and challenge ahead, as well as the absence of sufficient mental health care in the USA, I think audience members are best served by taking extra care in choosing which performances they should see. Call the theater ahead of time and ask about what you consider to be triggering to you. Do the research and make the choice in advance.”