Content warning: this story contains references to self harm and suicide. If you or someone you know is in need of help, you can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255. Additional resources are available here.

“We are who we are, we are, stronger than all our demons,” croons singer and songwriter Richard Yuan ’25 in the chorus of “We Are.” The song, produced for a mental health songwriting competition, recounts experiences of insecurity and emboldens listeners to be “free to be who we are.”

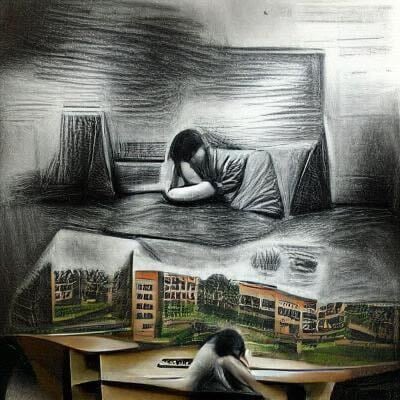

But despite the song’s uplifting tone, it evokes a deeply personal experience for Yuan: the feeling that he “isn’t enough.” For students like Yuan, mental health remains a significant challenge at Stanford. Since the outbreak of the pandemic, students nationwide have reported significantly higher rates of depression, anxiety and loneliness. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a stark warning at the end of March about youth mental health: more than four in 10 teens reported feeling “persistently sad or hopeless” during the first six months of 2021.

In 2020, Stanford’s Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) reported a sharp uptick in appointments amid virtual learning and social isolation. Classes eased their grading schemes from letter grades to satisfactory/no credit during spring 2020, and offered a satisfactory/no credit option during the 2020–2021 school year, to support students struggling with stress and quarantine. For many students, it was an opportunity to air their struggles in solidarity with their peers, as many felt the personal impact of quarantine.

Still, over a year later, the mental health toll of the pandemic has persisted. Recent student tragedies have bared more wounds among the Stanford community, spurring calls for a wider reckoning with and increased funding for mental health resources on campus.

The students I spoke to recounted episodes of suicidal ideation, depression, anxiety and shame that dampened an otherwise normal college experience. While their stories speak to the depths of private suffering at Stanford, they also offer hope: the students ultimately accessed counseling and found diverse ways to grow and recover.

‘Sometimes people just want to feel heard’

I meet Yuan one evening over Zoom, when he joins my call from a small, luminescent room in Munger 4. He sits mutely as I explain the interview procedures, his eyes quivering with contemplation.

He tells me coming to Stanford forced him to reckon with his mental health. In high school, Yuan was a star artist, immersing himself in acting and singing that helped him stand out among his peers. He didn’t have “the best social skills,” but his artistic talents helped people “look past the awkwardness,” as he performed for local stages and even the streets of his hometown, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

But when Yuan arrived on campus, the transition to college was harder than expected. He realized he didn’t “feel distinguished” among his peers, which he said took away what so easily connected him to others in high school. “Coming to a big university,” Yuan said, “I have to actually focus on my social skills rather than depending on external things because people are so much more impressive.”

He added that a year and a half of remote learning affected his ability to “hold a conversation” and spurred familiar feelings of self-doubt. “That kind of forced me to think about, ‘hey, is there something wrong with me personally?’” Yuan said. “I’ve been trying to figure out how to let go of self-judgment while having conversations here.” Grappling with a difficult transition to college, Yuan decided to focus on his mental health, which he said “revolutionized the things I do throughout the day.”

The first things he did were simple: start journaling, and taking a walk every day. He pulls out a green notebook, looking down at the pages as he speaks. “I write about how I feel after a given day [or] an emotionally impactful event. I also try to understand why I may feel frustrated,” Yuan said. “It’s helped me see the connections between events in my life and how I feel, and that level of awareness has really helped me feel more calm and make sense of things.”

Destin Fernandes ’24 echoed the importance of addressing mental health challenges on campus, as he dealt with depression and anxiety throughout fall quarter. He had been seeing a therapist over the summer in Massachusetts, his home state, and “was working really well” with them. But after coming to campus for the new school year, Fernandes couldn’t continue seeing his therapist due to state licensing laws, which restrict the location of patients seeking therapists in Massachusetts.

“I was out of any support systems because I was also away from my family and my friends,” Fernandes said. “So I basically was taken out of all the support I had, thrown into Stanford fall quarter, and expected to just transition.”

Without a therapist, Fernandes struggled to feel motivated in his classes and “got progressively worse” as the quarter wore on. By the end of Week 10, he was experiencing suicidal ideation, which he hid from his family and friends for fear of making them worry. By then, Fernandes had gotten in touch with a counselor through CAPS and later received medication for his depression and anxiety, which he says immediately helped him regain some energy and motivation. “I knew it was something I had to do for a while, but it took me so long, just because of how difficult phone calls were for me,” Fernandes said.

After receiving medication, Fernandes said his winter quarter progressed more smoothly, and he was finally able to find a regular therapist at an affordable price under Cardinal Care. When he came home for winter break, he also disclosed his struggles to his family, who ultimately supported him and reconnected him with his traditional support systems. Still, he says, it took too long for him to be vulnerable with friends and family due to the stigma around mental health.

For students like him, Fernandes said, being open about their mental health struggles can be essential to addressing them. “We should be focusing on these open conversations without feeling judged or like you can’t talk about them,” Fernandes said. “People don’t know the extent to which it can actually impact your life. So no one really is hurt by being more open about it.”

Fernandes added that Stanford’s culture, which he said prizes work and achievement over student well-being, can also contribute to a generalized stigma around mental health.

“The culture here is very much based on getting to where you want to be as fast as you can,” Fernandes said. “It’s cool if you can make friends on the way but you can dispose of them whenever, which I think really contributes to people not feeling comfortable enough to share their actual emotions.”

Though Stanford has committed to reinvesting in CAPS, Fernandes emphasized that more funding will be necessary to tackle the mental health crisis. But by sharing their stories, some students also see an inkling of hope: they are fighting the stigma and advocating for more support and resources.

“Sometimes [people] just want to feel heard, and to listen to what they have to say,” Vanessa Chen ’25 said. “And that’s literally all you need to do, just to sit there and be able to listen without feeling the need to react and respond to them.”

Silver linings, and the path to recovery

Elizabeth Schmidt ’25 last showed symptoms of depression in December. Dealing with “a complicated family situation,” Schmidt became estranged from certain family members at the beginning of fall quarter and grew heavily depressed as a result.

Transitioning to Stanford, Schmidt says, became a “downward spiral.” The combination of “rigorous academics, personal problems and my family all came and swooped in,” which affected her relationships and ability to connect with her peers. “I didn’t make many friends at Stanford at first.” Her grades suffered too — “it was consuming me,” Schmidt said.

But things got better. Fast forward to winter quarter, and her family situation had “cleared up.” Schmidt began to delve deep into materials science research, which has brought her “so much joy.”

“Exploring that passion, really finding where I belong, and finding that purpose is something that really motivated me and provides me happiness on a daily basis,” Schmidt said.

Another key aspect that helped her mental health, she added, was community. Schmidt regularly enjoys hiking with her friends at the Dish, indulging in hobbies like singing and photography and going on trips with her dorm-mates to San Francisco. “Just having the ability to go and talk to someone that I really care about is something that I love,” Schmidt said.

Chen echoed this sentiment, emphasizing non-academic activities as a way for students to tackle mental health challenges. Chen staffed for the National Youth Leadership Training, which teaches leadership skills to youth in Boy Scouts of America.

“I know that other people are looking up to me, so going to communities where I feel welcome and I’m serving a purpose makes me feel a lot better,” Chen said. “It helps me refocus and look at the bigger picture.”

As a musician, Yuan said he frequently incorporates themes of mental health in his artistry as a way to spread awareness. “That’s an easier way for me to share about mental health because when you listen to a song, you don’t have to respond. But you can still hear what is being said and resonate with it.”

Still, uncertainty abounds for some students. Schmidt says she worries about her financial status. Since she became financially independent, she has been in contact with Stanford’s Financial Aid Office, as her previous household income did not qualify her for financial aid. “It’s very terrifying and extremely stressful,” Schmidt said, as she had to take out a loan to cover her winter quarter tuition. She’s currently working two jobs and is still figuring out her summer housing, but she stays hopeful amid the shadows.

“It does weigh on me in the sense that I’m terrified I’ll slip back into [depression],” Schmidt said. “But at the same time, I know that deep down I won’t. So it’s kind of that false sense of anxiety looming over you.”

For students like Schmidt, recovery isn’t easy. But with more institutional support and a more open culture toward mental health struggles, they say, we’ll see a brighter, healthier campus.

“One day you’ll look back and love … the struggles you’ve overcome,” concludes Yuan in “We Are.” The stories of students like Yuan highlight that no matter the adversities, the path towards healing remains visible — aglow with signs of hope.