Walking into the gallery of the Hoover Tower, I watched kaleidoscopic collections of Japanese propaganda posters unfold before me, luring me in with their weight of history and air of mystery. The “Fanning the Flames: Propaganda in Modern Japan” poster exhibition sheds light on the multifaceted forms of wartime disinformation, which remains especially relevant today with the ongoing Russia-Ukraine War.

The exhibition was sponsored by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives, displaying a variety of propagandist artworks in Japan between the Meiji era and the end of World War II. Taking place until July, it features items ranging from tapestry-sized scrolls to letter-sized paper play cards that entertained children.

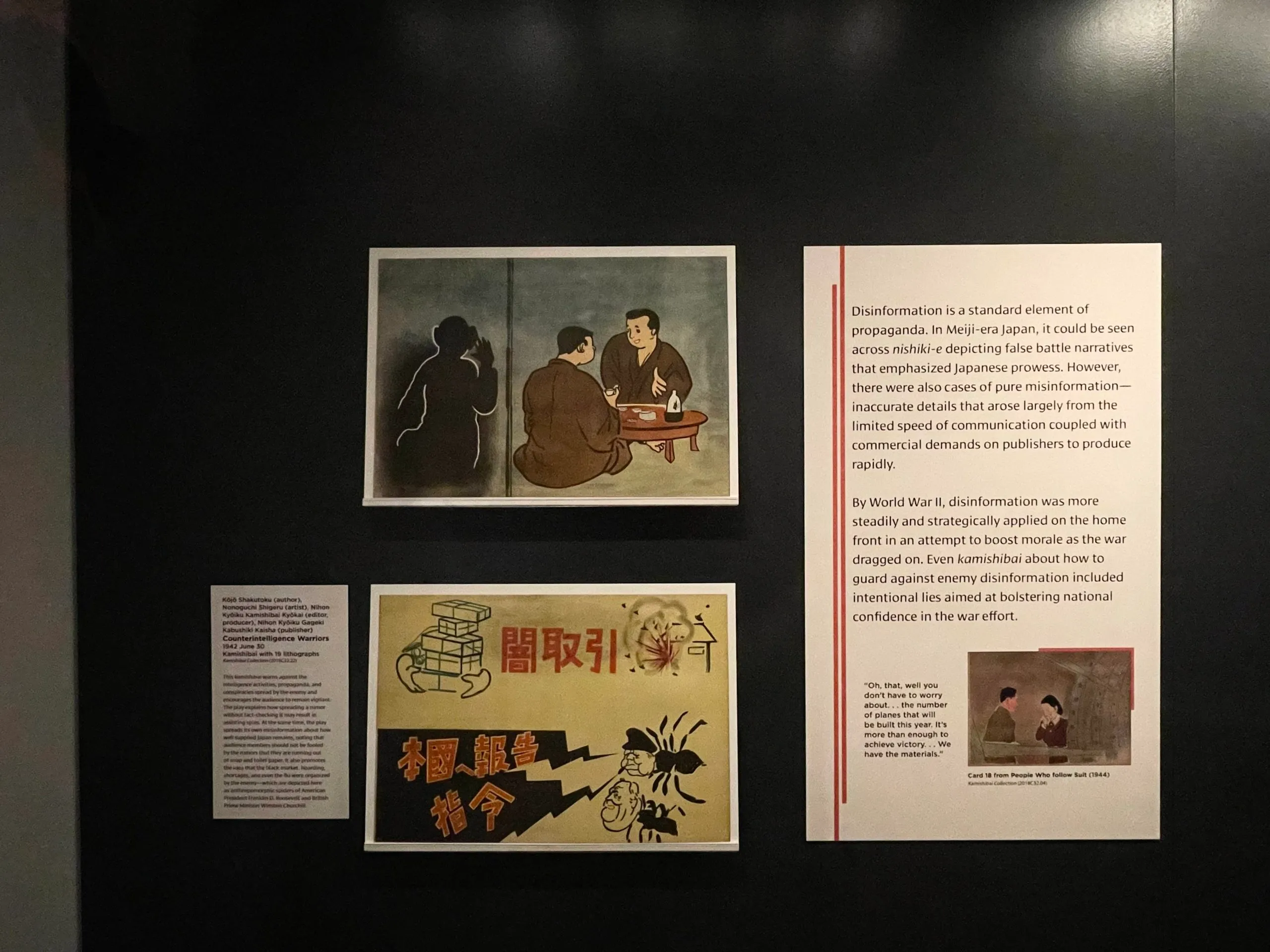

“Fanning the Flames” explores how modern Japan employed popular arts as propaganda to inspire imperialist fervor. I was most struck by the incorporation of ideological biases in “kamishibai,” paper plays consumed by young children. Each set contains letter-sized illustrated scenes with dialogues to be read out. A 1942 kamishibai warned against the danger of spreading rumors about the war, while also propagating disinformation that the Japanese army’s invasion of Asia was still well-supplied. The disheartening paper play demonstrates the pervasiveness of wartime disinformation campaigns, especially on the home front. Not even youth, who lack true independent judgment of the world, were spared from the propagandist efforts. The unassuming spoonfeeding of information in kamishibai reminds me of the ongoing untruths that Russian domestic channels are spreading to its citizens regarding the war in Ukraine. Russian citizens today are left in the dark, just as Japanese citizens once were.

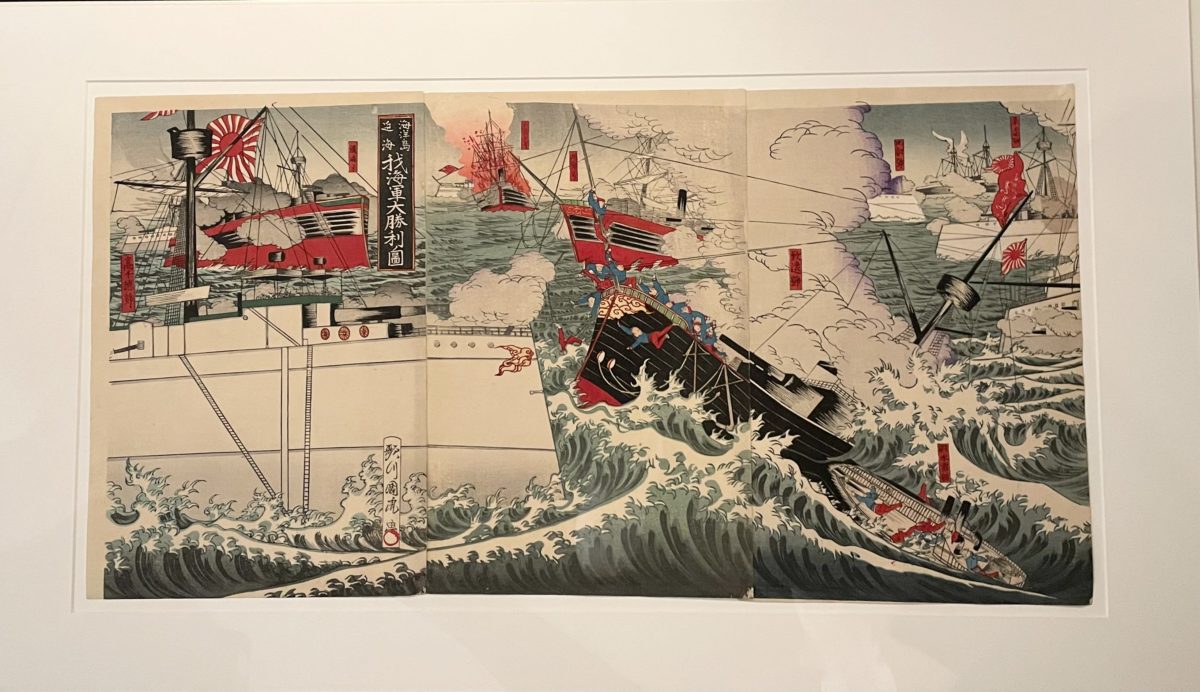

Many of the posters took the form of “nishiki-e”, or multicolored prints made from Japanese woodblock printing techniques, featuring angular lines and sharp hues. As someone who has a “Great Wave off Kanagawa” tapestry on my wall, I was surprised to find similar bright, violently whirling waves in the poster “Great Victory for our Navy near Haiyang Island,” which romanticized the Japanese navy’s victory over the Chinese Beiyang Fleet in 1894 during the First Sino-Japanese War.

The stark contrast between the bright red Beiyang Fleet and the coral-blue sea, which consumes the battleships, creates a mesmerizing beauty that disguises the tragedy of maritime war. Meanwhile, the Japanese ship stands firmly in the brutal waves with its head held high, sipping the sweet wine of triumph. Even to the less-educated Japanese public at the time, the poster’s aesthetic would have effectively fed them the government’s simple and clean narrative: the mighty army heroically defeated the weak Qing Dynasty fleet.

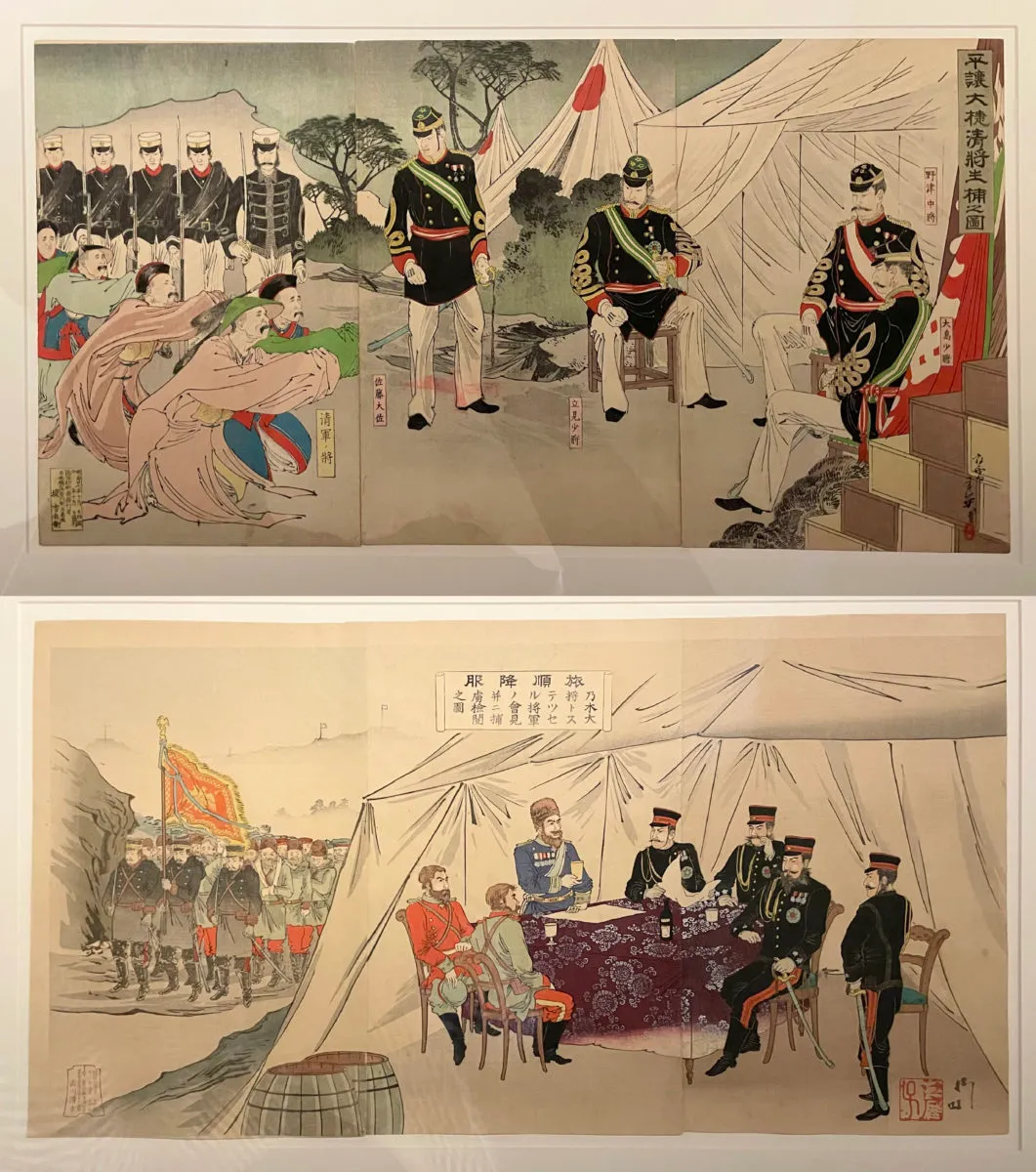

While many of the posters featured Japanese dominance, enemies were depicted in various kinds of defeat. Making my way through nishiki-e prints that depicted the surrender of Chinese and Russian generals, I was struck by the contrast between the 1905 poster “The Surrender of Port Arthur” and the 1984 poster “The Capture of Chinese Generals and Victory in Pyongyang.” The former portrays a scene in which a Russian general sits at a table, erect, as he negotiates the terms of his surrender with likewise postured Japanese officers; the Russian prisoners in the backdrop stood with dignity. In comparison, the latter features Qing generals pleading on their knees, their bodies bent forward and their faces filled with fear of death, while the Japanese generals peer at them disparagingly.

As the exhibition program noted, the contrast directly points to the imperialism and racism that drove the Japanese invasions of China. With the ultimate goal of making Japan equal to European countries through territorial expansion and modernization, Japanese officials viewed the Russians as a part of the white European “rulers” of the globe, a superior race and status for which they strove. The propaganda nishiki-e displayed their respect for the Russians and perception of other Asian races as inferior to them. While these biases are apparent to a contemporary audience, to the eyes of the Japanese public then, having had little contact with the outside world, the propagandist portrayal may have been more easily accepted. Meanwhile, I was reminded that modern Japan is not alone in feeding its citizens a biased narrative. During the same era, propaganda art in the U.S. portrayed the Asian nation as a ruthless enemy and justified the unfair internment of Japanese Americans, emblematic of the anti-Asian racism that persists till this day.

Displaying how wartime propaganda was infused with popular Japanese art forms around the early 20th century, “Fanning the Flames” takes us through the cultural manifestations of Japan’s imperialist efforts in Asia and offers us a fresh perspective on disinformation and propaganda today. While we on this continent seem to be removed from the brutal military conflicts on other parts of the globe, we constantly seek out information channels, which feed us subjective interpretations or misinformation that we are unconscious of in our urgency to learn. Nowhere is this better seen than in the Russia-Ukraine War today, with the Russian government’s disinformation campaigns misleading many, in addition to the built-in echo chambers preventing information to get to either side of the debate. Viewing the propaganda art from modern Japan, a place removed from me both geographically and temporally, I gained a new understanding of the omnipresent nature of the manipulation of information.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and contains subjective opinions, thoughts and critiques.