President Joe Biden announced the July 31 CIA drone strike killing of al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri to the nation on Monday. Stanford experts and veterans said they supported the strike and expressed measured hope that Zawahiri’s death will have dealt a major blow to al-Qaeda.

“I’m cautiously optimistic that this will be partially effective in degrading al-Qaeda,” said Dean Winslow, a Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (FSI) senior fellow and medicine professor.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s most-wanted terrorist for 11 years, Egypt-born Zawahiri dedicated his life to radical-Islamic terrorism at the age of 15 when he created an underground cell in 1966 with the intent of deposing Egyptian president Gamal Nasser. A few years later, Zawahiri joined and soon rose to leadership of the terror organization known as Islamic Jihad.

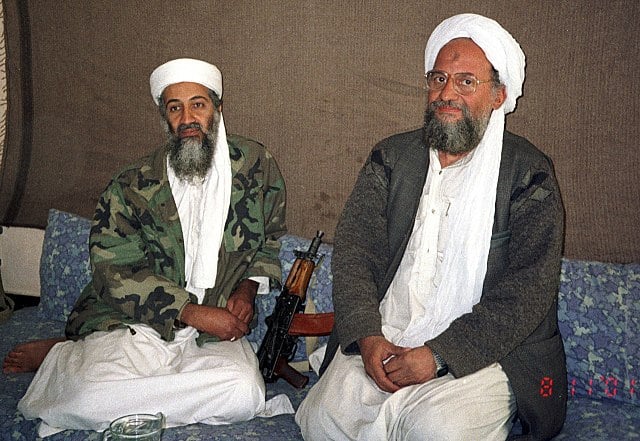

Zawahiri, who the Islamic Jihad officially declared as leader in 1991, became one of Osama bin Laden’s most prolific operatives in the 90s, forming terror networks in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, Chechnya, the United Kingdom and the U.S. In 1998, Bin Laden and Zawahiri formally united al-Qaeda, the Islamic Jihad and several Asian-based Islamic organizations and called for the execution of Americans.

Bin Laden also named Zawahiri as his second-in-command, and together they planned the Sept. 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Zawahiri assumed leadership of al-Qaeda after the U.S. Navy SEAL Team 6 killed Bin Laden on May 2, 2011.

With Bin Laden dead, the U.S. considered Zawahiri to be the most grievous living terrorist and pursued him for 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies as well as his leadership of al-Qaeda. Although Zawahiri long evaded the U.S., and was even rumored to be dead until he called for terror attacks on the West on the twentieth anniversary of 9/11, U.S. intelligence kept watch for Zawahiri. And when intelligence caught sight of him residing in a Kabul safe house while visiting the Taliban, a drone strike operation was prepared. At 6:18 a.m. Kabul time, two Hellfire missiles ended Zawahiri’s life when the terrorist stepped onto his balcony.

“Now, justice has been delivered, and this terrorist leader is no more,” said President Joe Biden.

FSI senior fellow emerita Martha Crenshaw called Zawahiri’s death “a significant blow to al-Qaeda.”

“It follows on a series of strikes against al-Qaeda and ISIS leadership, going well beyond Bin Laden,” Crenshaw wrote. “It shows that the US holds firm to the position that ‘decapitation’ strategies work. Also that US intelligence agencies have long memories.”

Crenshaw added that Zawahiri spending his final hours in the Afghan capital of Kabul “should remove any doubts” about the relationship between al-Qaeda and the Taliban.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken released a Monday statement condemning the Taliban government of Afghanistan for violating their 2020 agreement with the U.S. In the agreement, the Taliban promised to “prevent the use of the soil of Afghanistan by any group or individual against the security of the United States and its allies” and specifically named al-Qaeda as one such group.

Jeff Phaneuf MBA ’23, a Marine veteran and director of advocacy for the nonprofit No One Left Behind, an organization that advocates for and helps facilitate the resettlement of Iraqi and Afghan allies into the U.S., expressed relief at Zawahiri’s death. However, similarly to Crenshaw, he noted that Zawahiri’s presence in Kabul holds dire implications for the nature of the Taliban government.

“As someone who fought in the Global War on Terror and as someone who remembers 9/11, I am glad to see this remorseless terrorist removed from the battlefield,” Phaneuf wrote. “But the fact that he felt safe enough to move to Kabul under the Taliban regime is clear indication that the work to save our allies left behind in Afghanistan is not yet done.”

Phaneuf added that No One Left Behind would remain alert for “Taliban reprisals,” which he fears would come in the form of Taliban interference in the continuing evacuation of the U.S. military’s Afghan combat allies.

Bradley Boyd, a fellow veteran and a Hoover Institution visiting fellow who formerly directed an artificial-intelligence initiative in the Department of Defense, wrote that the U.S. must ask “hard questions” of the Taliban moving forward. He also shared doubts that the elimination of Zawahiri would encumber al-Qaeda.

“We should refrain from exaggerating the significance of this strike,” Boyd wrote in a statement to the Daily. “I wouldn’t expect his death to make any real difference in current al-Qaeda operations or planning. Ultimately, I think this action is a small sideshow in the ongoing containment of Al Qaeda, though it certainly reiterates that declaring yourself the leader of Al Qaeda is very hazardous.”

Winslow agreed that Zawahiri was “an enigmatic figure,” but he said Zawahiri’s decades-long central role in the planning and execution of terror attacks gave great meaning to his removal.

“As a Christian, I am concerned anytime one human being takes another human being’s life,” Winslow said. “But in a situation where you have a person responsible for the deaths of thousands — and if you extend that to the war in Afghanistan, the deaths of 2500 coalition forces and 100,000 or more Afghan civilians — that’s a big deal.”

Winslow added that Zawahiri’s elimination reminded him of his station at Bagram Airbase at the time SEAL Team 6 flew from it to eliminate Bin Laden. Winslow recalled that he and those he served with “applauded that action” upon receiving the news, and Winslow related it to how he feels about Zawahiri’s death in present day.

Winslow shared “cautious optimism” that Zawahiri’s death would “be at least partially effective in degrading al-Qaeda.”