Living the straight life

It’s an unspoken tradition here in the Philippines for relatives to ask girls at family reunions if they have a boyfriend. Never is it: “Do you have a boyfriend or girlfriend?” Always, that straight-to-the-point question: “Do you have an opposite-gender friend that you like to engage in romantic activities with?”

Most of the time, I’ve always answered that peculiar question with a “No, I don’t have a boyfriend.” It felt like the polite thing to do. I never questioned their inquiries, nor did I have the courage to correct them with a “or girlfriend?” I knew that this was a tradition I had to get in line with, lest I be ostracized by the very people who raised or befriended me.

Despite this, it was rather easy for me to accept my bisexuality. In my younger brain, I thought that since I liked men too, it would be easier for me to hide whatever feelings I had for women. “I just don’t have to mention it,” I told myself. I wasn’t ready for people to know that I was different. This internal rationale was a desperate act to prove to everyone else that I was just like them, not some other “queer.”

And so I began to feel like an actor in my own life — a fraud, even — playing a role that I’d been forced into by rule of birth. When my peers at school became boy-crazy for the upperclassmen, I too would squeal in joy whenever a cute boy went by our classroom. I brushed off a crush on a girl as a typical “girl crush,” something everybody joked about having too. I acted like I was in love with a boy I only liked a moderate amount. From the clothes I wore to the jokes I told to the hobbies I enjoyed, all were specifically curated to prove my “straightness.”

It wasn’t until the COVID-19 pandemic that I began to break out of this cycle. Of course, the pandemic wreaked its havoc on me too — my anxiety worsened, and my life as I knew it came crashing down around me. But no pandemic or six-feet social distancing protocols could worsen the sense of isolation that I already felt as a queer person. And to my surprise, the spare time I found in quarantine gave me the space to explore my relationship with my sexuality — and explore I did.

“Other gay people exist?” — Me, in 2020

“Bungou Stray Dogs” (BSD) is a popular Japanese anime and manga series that follows a special detective agency as they fight mafia organizations with special “abilities.” Its characters include Atsushi Nakajima, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Fyodor Dostoevsky. If you are a fan of classic literature or were forced to take AP English Literature, you have probably encountered at least two of these names. The characters from “Bungou Stray Dogs” are based on famous writers, and their “abilities” are based on their famous works. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s ability, for example, is called “The Great Fitzgerald” as a nod to the author’s famous novel “The Great Gatsby.”

Despite its peculiar concept, the anime explores many dark themes, including existentialism, abuse and redemption. But the one that most caught my eye was the overarching theme of being a “stray dog,” an outcast in society. Atsushi Nakajima, the main character, was kicked out of an orphanage for possessing the ability to turn into a tiger. He lives in shame for the pain he has caused others. After stumbling upon eccentric friends from the Armed Detective Agency, though, he suddenly feels a sense of belonging, especially with most of the agency’s employees being “ability users” like him.

This story resonated a lot with me as a queer person. Although I don’t have transformative abilities, I feel a lot of shame for the way that I am. “Why can’t I be the way other people want me to be?” was a constant refrain plaguing my mind. Every day, I feared that my Christian family would find out about my queerness and accuse me of turning against God. I lived in constant regret for letting their beliefs down and cursing them with a queer child. But with time, just like Atsushi, I’ve come to accept my sexuality. And like him as well, I found a sense of belonging with other “stray dogs.”

As I continued to watch the anime more, I was led astray to “BSD TikTok,” or the BSD fandom side of the social media app. I knew what to expect: occasional fan edits and characters being “shipped” together. But it was the massive number of unapologetic queer fans who drew my attention.

It was not my first time in a queer-dominated fandom, as I had been a K-Pop fan before. It was, however, the first time I had ever been in a queer-dominated space where people were openly queer and discussed their queerness.

I had known I was bisexual for a long time, but it wasn’t until I saw people celebrating the bisexual subtext of a character that I suddenly felt that my own sexuality was alright too. I grew up being told that topics like sexuality were improper to discuss. Yet, here, fans were celebrating their sexuality, gender and pronouns. I was shocked.

It was okay to be queer. It was okay to be bisexual. I was not alone.

Dipping my toes into the queer-dominated fandom of BSD was only the beginning. Thanks to TikTok’s algorithm, I found myself engrossed in other queer spaces too, surrounded by people just like me. In real life, I’ve always felt like the odd one out: the one who wore the wrong clothes, believed the wrong things and liked the wrong people. But after seeing video after video of people talking about their identity, their same-sex partners and their queer-related experiences, I suddenly found myself to be the right kind of person. I’ve come to realize that I was simply so afraid of embracing myself, of being different in a sea of people who didn’t understand difference in identity.

The power of the Internet

In talking to Stanford’s queer community, I discovered that I was not alone in rediscovering my queer identity through the media and Internet during the pandemic.

Dyllen Nellis ’24, having chased the “straight girl” aesthetic all her life, described how she felt like she had to act and look straight because everybody around her did — a phase I was also guilty of in the past.

“That’s what all the girls around me did, [and] I always tried to be like them,” she told me.

It is crazy for her to believe now, but there was a time in her life that she thought herself to be 100% straight. However, it wasn’t until she dipped her toe into TikTok (and watched the TV show “Atypical”) that she found herself accepting her place in the queer community. Her feed became “very gay very quickly,” she said.

“Now, I can break out of this,” she said, referencing her chase to look “straight … and dress more creatively without feeling like I have to subscribe to a certain aesthetic.”

Anna Zheng ’25 also believes that the media played a huge role in her journey to self-discovery. Zheng knew that she found girls attractive for a long time, but like most queer people, she shoved that thought away. But when she participated in a theater production of Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night,” she realized that she was bisexual.

“Yeah, this is not going away. I definitely like girls,” she told me.

Zheng talked about how affirming it was to see queer comics, comedy and other content on the Internet. For her, it made “such a difference” when she saw people like herself in the world.

“It’s like I can be both Asian and queer if I see people who are Asian and queer,” she said.

To the stray dogs

The most terrifying thing on Earth is discovering that you are different from your parents and friends. I chuckle now at the naive and desperate acts that younger me did to fit into a heteronormative world. I knew that I didn’t belong, but I continued to force myself in between people who I felt worlds away from.

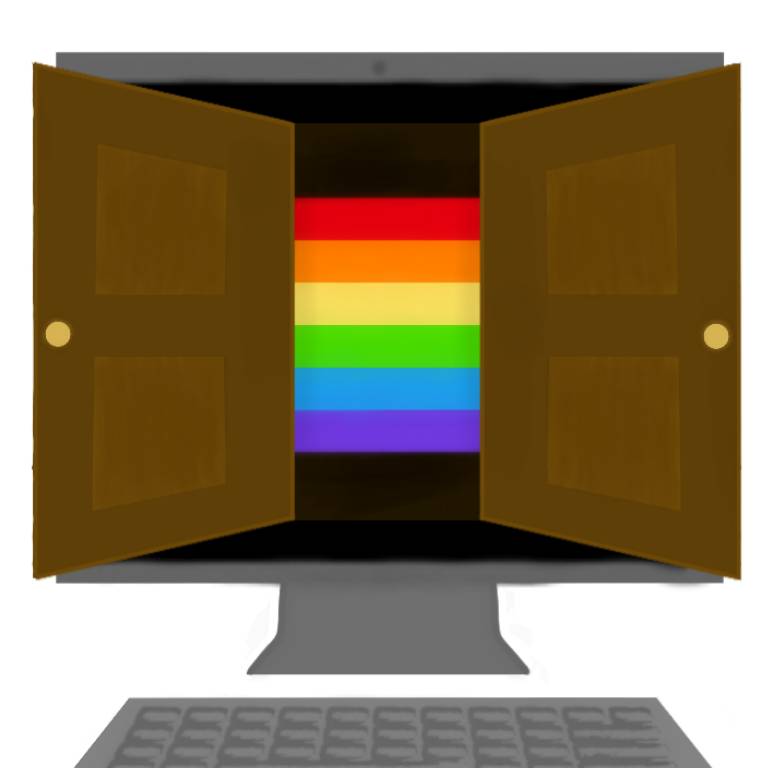

I’ve grown since then — met people like me and learned to accept the part of my sexuality I’ve locked away in the closet. However, I don’t mean to preach. The pain will always be there… but, maybe that’s okay. Being different is okay.

I’ve come to realize that fearing my difference is unnecessary; to fear it means giving into society’s prejudices. Instead, it must be welcomed with open arms. Celebrated, even! After all, this difference made me belong somewhere, a feeling I would not have felt pretending to be someone I’m not. It brought me closer to who I am: a bisexual, a lover of all and a stray dog, a person who is proud of this difference.