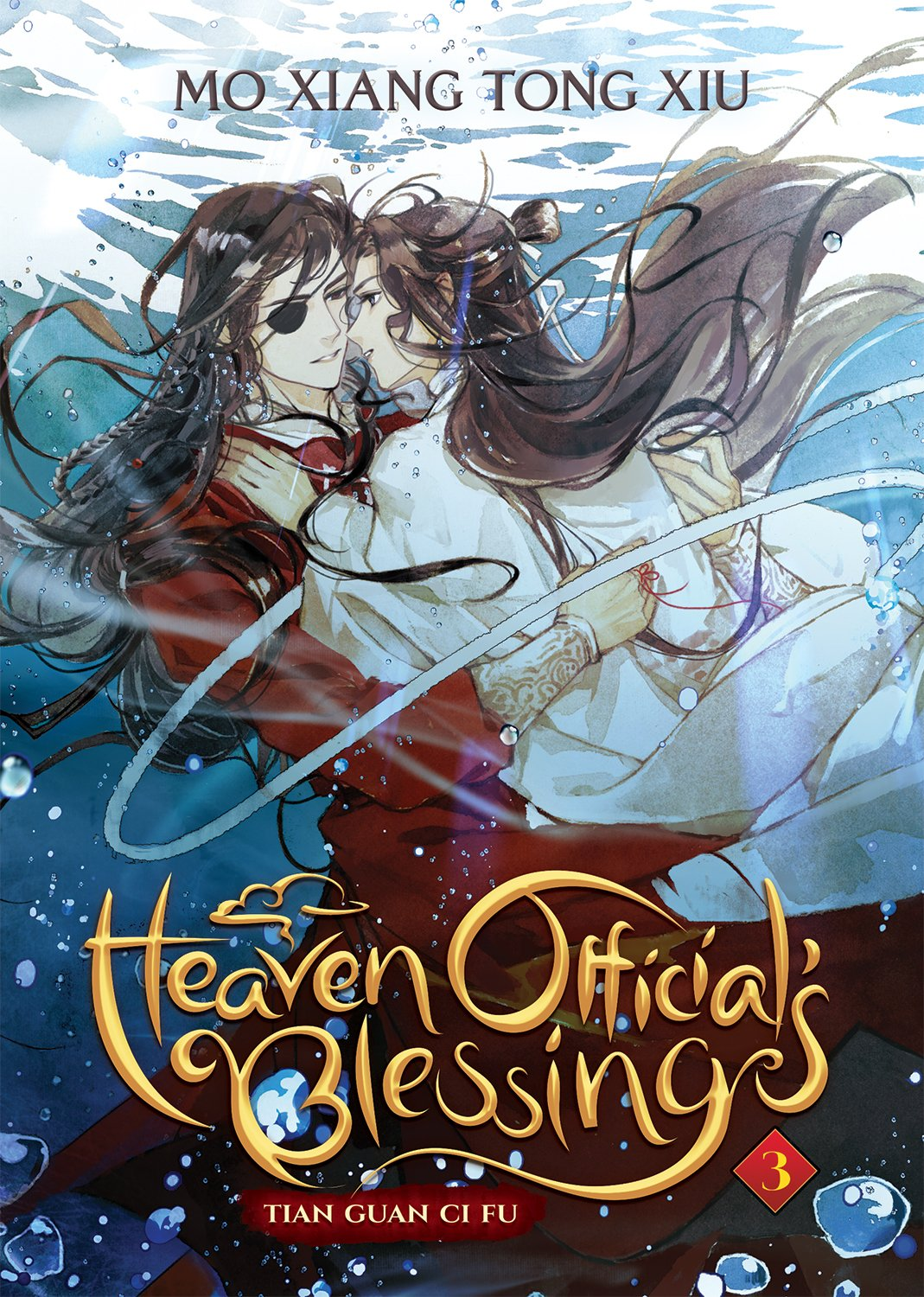

With unique variations on queer representation and true love, translations of danmei, a genre of gay romance fiction in China, quickly rose to popularity in the United States in recent years. The highly anticipated English publication of the third volume of Mo Xiang Tong Xiu’s (MXTX) “Heaven Official’s Blessing” became available to purchase on July 12.

Fans of “Heaven’s Official Blessing” have been anxiously waiting for its arrival. One Goodreads reviewer hyperbolically wrote, “Everyday i [sic] have to fight the urge to bargain my soul to the devil so i [sic] can read this sooner.” A quick search on Google Trends indicates a rapidly growing interest and relevance to Americans since 2019.

To catch you up on the hype: The series follows the lives of two characters that start as unlikely acquaintances — Xie Lian, a god in the heavenly realm, and Hua Cheng, a king of the ghost realm — but fall in love through their journey across the realms, uncovering their interwoven pasts along the way.

The blossoming relationship between the two, spanning over 800 years of tragedies and heartbreaks, captured romance readers, with the series even making it (along with two other MXTX titles) onto the New York Times Best Sellers list. The danmei genre gained even more international appeal with MXTX’s other book, “Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation,” which has been officially translated into 10 different languages.

In preparing for “Heaven Official’s Blessing Vol. 3” release, I transcended into the depths of MXTX’s xianxia (cultivation fantasy) realm to explore the impact that danmei novels can have on the LGBTQ+ community in China.

When danmei fan and student researcher, Vivian Zhu ’23, and I discussed these novels, she said something that really defined the allure of the romance: “Some amorphous god wanted these two exact people together — gender does not matter, nothing matters, they were just meant to be.”

Beyond the blissful appeal, danmei novels, largely dominated by female writers, can be seen as a departure from China’s gender inequality and the societal pressure placed on the so-called “leftover women,” or those who do not settle down but instead remain single past a “socially acceptable” age. The danmei genre provides a safe escape from the male gaze. Through being a “sexualizer” and voyeur, women have a platform to explore their sexuality and desires in homoromantic and erotic love stories.

However, danmei’s utilization of gay men as conduits for female fantasies can impose heteronormative expectations and potentially misrepresent the LGBTQ+ community in China — a bias that danmei readers must acknowledge.

Third-year Ph.D. student in modern Chinese literature and danmei lover Ting Zheng believes the patriarchal dynamic of male-dominant/female-submissive roles are transplanted onto the gong–shou (top-bottom) archetype. She said that some “authors will design the shou, the being-dominated power, to have babies via male pregnancy” in order to demonstrate feminine traits, for instance.

According to Zhu, this allows readers to view stories through heteronormative conventions without being burdened by a queer lens, “a concept that is considered bizarre in a more conservative society like China.”

Exploration of the “versatile form” or hugong — where two partners can have both dominant and submissive traits — can help the genre provide a more diverse representation of the LGBTQ+ community. The underlying heterosexual frame in danmei erases the diversity of same-sex partnerships, the struggles of coming out and the societal stigma gay men face in real-life China.

Unfortunately, gay danmei writers’ portrayals of realistic homosexual relationships haven’t become as successful, since their content does not align with the female consumers’ interests. Gay author Nankang Baiqi had stories that never gained traction because they were considered too “reality-oriented” with their depictions of gay struggles like social ostracization, and author Feitian Yexiang only became popular when he switched from writing “realistic gay stories to fantasy novels.”

“Many people that write, read or are fans of danmei are pretty homophobic in real life,” said Zhu. She has seen social media posts on Weibo, a Chinese social media platform, where danmei fans say that real gay men are the enemy of people, are dirty and transmit monkeypox. It is rare for any commenters to refute those claims, Zhu said.

Furthermore, Zhu believes danmei novels can be harmful to the LGBTQ+ community because “it can spread toxic sexual norms and expectations” and “increase visibility in a politically unsavory way.” After danmei adaptations like The Untamed became popular, the Chinese government censored an upcoming LGBTQ+ romance show due to the male character’s effeminization and corruption.

Despite its shortcomings, danmei’s presence provides a space for readers to explore queerness, where they otherwise would not have encountered the subject. Zhu said the genre’s popularity could contribute to a “cultural vibe shift in the younger generation” in China’s gender and sexuality discourse, with queerness becoming more normalized.

Perhaps this shift is already beginning. Zheng shared her friend’s journey with danmei novels as an example: “Because of this genre, she is really friendly toward the LGBTQ+ community and is willing to help or encounter members.”

If literary representation can inspire change, it is even more important for danmei authors to write accurate depictions of the LGBTQ+ community, since their writing can help audiences become more accepting of queerness and, one day, may contribute to the societal acceptance, normalization and protection of gay rights.

Even though Hua Cheng says swoon-worthy phrases like, “to some, the very existence of a certain person in this world is in itself hope,” I can’t help but wonder if the author appropriated her idealized heterosexual relationship onto gay men. While MXTX writes fantasy novels, danmei authors like her have a responsibility to write true representations of same-sex couples and gay men; their experiences are not a commodity to gain profit.

Although Pride Month is over, the queer experience is continuous, and media representation is essential to how individuals form their opinions on this marginalized community. It is important to be an active observer, critiquing content that you enjoy — in my case, danmei novels like “Heaven Official’s Blessing.” Otherwise, it could have unintended ramifications, such as reinforcing a heteronormative narrative in a homosexual genre, suggesting the content ultimately rejects queerness.