Dear Stanford: I am Karen (Kuh-Ren), not “Karen” (Care-In) or “Korean.”

Dear Stanford: The Karen people are an ethnic group in Myanmar-Thailand that have been persecuted by the Burmese government and military for over 70 years now. I was born in Mae La refugee camp in Thailand because of this.

Dear Stanford: There is a quote that has been ingrained in my brain ever since I first heard it from my parents and the community around me. “In twenty years, you will only find Karen people in museums,” announced Burmese Army General Maung Shwe as he walked over our flag in 1997. This was not only a threat to my people’s lives, but it was also a threat to our culture, heritage and stories. Although twenty years have passed by now and my people are still alive, the intent to eliminate us is still present.

Dear Stanford: What is the difference between genocide and ethnic cleansing? According to the United Nations, genocide is the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group” whereas ethnic cleansing is “rendering an area ethnically homogeneous by using force or intimidation to remove persons of given groups from the area.” Though both may involve murder, rape, deliberate military attacks and other crimes against humanity, the “intent” behind these atrocities are what will make the world finally take action.

Dear Stanford: Over 4,300 Karen people have been killed and over 200,000 civilians have been displaced since 1989. I wonder how many deaths were unaccounted for. I wonder how many more of my people’s deaths need to occur for the UN to count it as “genocide,” for the world to recognize it as that and for actions to finally be taken.

Dear Stanford: A few months ago, there were several attacks on the Karen villages. The Burmese military, Tatmadaw, burned houses and fired about 30 airstrikes. Over 130 people were killed. The rest fled to the jungles and tried to escape to Thailand’s refugee camps where they were rejected. My aunts, uncles and cousins from my dad’s side were some of the people who fled to the jungles. They had to hide in caves in order to survive.

Dear Stanford: Do you know what life in a refugee camp is like? It is crowded and unsanitary. The education inside the camps is limited and there is a lack of access to food and healthcare. There is a fence around the camp so that no one can enter or leave. There are Thai soldiers patrolling each side. There is no freedom. There are only restrictions.

Dear Stanford: For the Karens who have post-traumatic stress disorder and other mental health problems because of the horrors they experienced and saw, the difficulties inside the refugee camp do not make it easier. But being alive counts for something — right? Staying alive is important, even if it means using beers, cigarettes and abuse as an outlet for what cannot be said or told: the traumas and nightmares of almost not making it; of seeing your own brother die right in front of you; of the bullet in your left lung that has now become a part of you.

Dear Stanford: For the longest time, refugees and immigrants are perceived as job stealers, illegals, undocumented, pitiful, desperate and uneducated people. We are blamed for migrating to a new country and trying to start a new life, as if we are at fault for the atrocities we faced. We are told to “go back to our country.”

But what if there is no country for us to go back to?

Dear Stanford: I do not have a country; my people are displaced and systematically oppressed by the country that is supposed to be “protecting” them. And while some of us were born in the refugee camps in Thailand, Thailand is not our country. We have no rights, not in Myanmar nor in Thailand. We are only but children of no nation.

Dear Stanford: I am alive. I should be grateful, right? I should be grateful that I only lived in Mae La refugee camp till I was 5 years old. I should be grateful I have all these opportunities in front of me when my own people are dying back home.

Dear Stanford: And I am grateful. I am grateful for the sacrifices my parents made to provide my siblings and me with a better life. I am grateful that my people are continuously fighting for our ‘country’.

But there is a pressure, and it haunts me.

Dear Stanford: Do not complain. I learned there is no room for complaints when your people are dying. Why am I even complaining? I have opportunities that my people do not have. My people are struggling; they are bleeding on the ground. Yet I throw complaints out like stones, hitting them when they are already down.

Dear Stanford: I am the future of the Karen people. I should be better. I need to achieve things others cannot.

So why is it that when I enter school, my ethnic identity no longer matters? I became Mu Hsi, or just another Asian girl. I am no longer Karen, a refugee or an immigrant. I am Mu Hsi and no one knows about my people or what they are currently going through.

But when I am home, I am Dah Pae – the Karen girl with Karen parents; the Karen girl whose parents had to flee to a refugee camp; the Karen girl whose parents immigrated to a foreign country, leaving behind their own parents and siblings so that they could give their children a life without worries. The Karen girl… Karen… K’nyaw… K’nyaw Mu…

Dear Stanford: When you look at me, what do you see? Do you see my different identities or do you only see one? Do I look like a typical refugee or are you shocked to know that someone of an “unknown” background has made it this far?

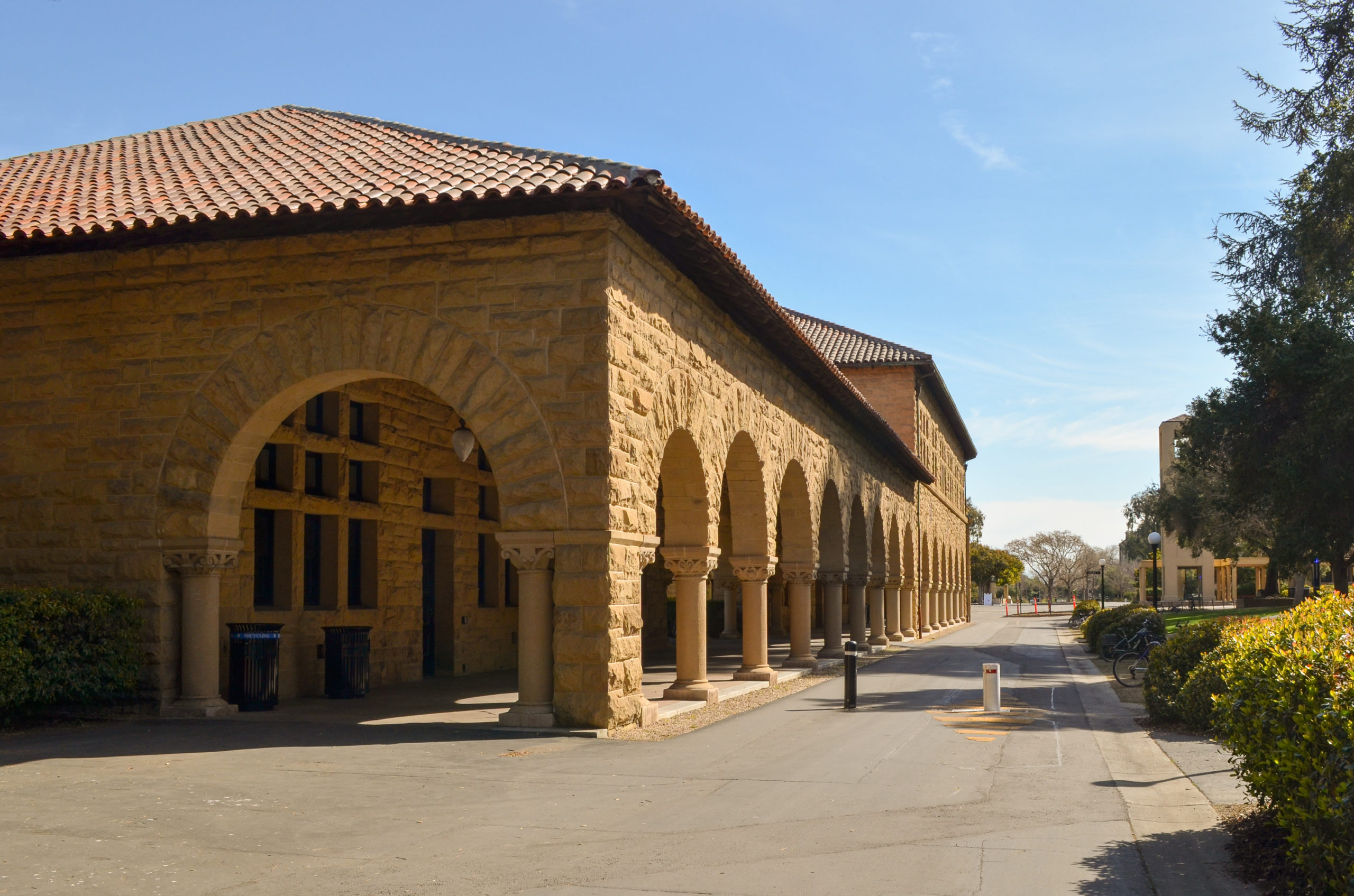

Dear Stanford: Can you see me? I, a Karen refugee, am right in front of you. I am everywhere around you. I am in your dining halls, lecture rooms, fountains and dorms. I am here.

Note: K’nyaw means Karen. Mu means girl.