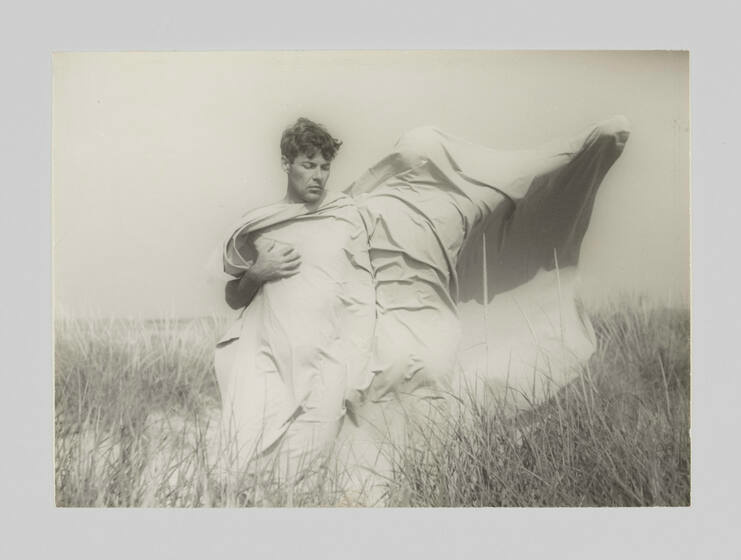

The first time I saw a photograph by the arts collective PaJaMa was five summers back, when a couple works were on view at the Whitney in New York. The piece I had the most distinct memory of was “Glenway Wescott, Fire Island”: the poet Wescott appears draped in a white, flowing cloth, the silhouette of an unknown body next to him. Both figures stand on the grassy shores of Fire Island. In the distance, a thin trail of water snakes across the landscape.

It’s a strange photo to decipher, like a signal blared from deep within a dream. I always liked the smallest details of the piece: Wescott’s downturned gaze, the white cloth that spreads across the center of the photo like a misshapen orchid, the flattened movement of the cloth that makes it appear simultaneously marble-like and billowing, the suggestion of a summer breeze in the background. It’s a quizzical piece, but it lingers in the mind; all the surreal details slot together perfectly and become evocative and atmospheric.

This dreamy haze was the hallmark of PaJaMa’s photography. Formed in 1937, the collective consisted of the American magic realist painters Paul Cadmus, Jared French and Margaret Hoenig French; the name “PaJaMa” was formed from the first two letters of each member’s name. The collective lasted until the early 1950s and was enmeshed in the art world in New York. More specifically, it was deeply entrenched in the queer art world.

The trio often took photographs while vacationing on the beaches of the Northeast coast, including Fire Island in New York and Provincetown and Nantucket in Massachusetts. Many notable figures from the 1940s New York art world appear in their photographs, including playwright Tennessee Williams, fashion photographer George Platt Lynes and museum coordinator Monroe Wheeler.

Even today, PaJaMa’s photos still feel incredibly modern. The form of the body is accentuated: models in PaJaMa’s photographs often pose with ballet-like grace, highlighting the simple, clean lines of their silhouettes. The natural world, too, is sharpened into abstract shapes: tree branches fan out through one piece, or a sandy shoreline cuts straight through the center of another. Minimal props are used; a knotted rope or a towel might appear in an occasional photograph.

In another photo, “Margaret French, George Tooker and Jared French, Nantucket,” the two collective members and American painter Tooker pose on a set of stairs by the beach. We see the silhouette of the stairs, as well as the artful composition of the three artists’ bodies. The piece is a criss-crossing network of lines: while the stairway railing crosses the piece downwards diagonally, the figure on top points upwards diagonally; two figures point upwards at different ends of the piece as the stairs zigzag between their silhouettes. The piece feels so clean and composed, yet, as in a dream, multiple signals are flashed simultaneously.

Something about summer, when the days melt into each other and everything feels a little more possible, is so sacred. And it’s precisely the atmosphere that is captured in the photographs of PaJaMa, with those bodies posing on the shore and the sea silently waiting in the background. Anything could happen; something indecipherable, something dream-like. I like holding on to this summertime feeling, and I find myself returning more and more to PaJaMa’s photographs as September disappears and we head straight into the heart of autumn.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.