L. Song Wu’s ’24 painting exhibition, “Gleaming Things,” was on display at the McMurtry building this past week. The show consists of five paintings, each expressing dysmorphia tied to perceptions of Asiatic beauty, as well as American traditions of passion and violence.

All paintings feature the interaction between an ‘anime girl’ and Wu’s self-portrait. ‘Anime girls’ — originated from Japanese animation popularized within the West in recent years — typically lack substantive character arcs and have overemphasized eyes and body silhouettes.

“The anime girl is not real. She cannot consent. She is a fantasy that we both despise and desire; she is both the Madonna and the whore,” said Wu.

Wu paints herself into the scenes alongside the anime girl, not as a way of narcissism but to understand the mythologies that have shaped her. The act of painting a self-portrait is more than copying exact details but rather a translation of demons and desires.

“I didn’t want them to strictly look like me in real life. Painting myself made me appreciate my body a lot more,” Wu remarked, referring to her self-portraits.

In the paintings, Wu’s face is an exaggerated pink color while the anime girls are painted with more fleshy tones. She commented that those who’ve seen the exhibit associate her face’s flush with shame, guilt, or embarrassment.

“I was particularly interested in this concept of Asian glow… and this idea of luminosity, gleaming things,” Wu said, echoing the exhibit’s name. The phrase is taken from a chapter in Annie Anlin Cheng’s book “Ornamentalism,” which focuses on the conflation of the “oriental” and the “ornamental” in Western perceptions of Asiatic femininity.

Wu borrows inspiration from a variety of sources. Many of her paintings are taken from popular cultural scenes of white American men, whom she replaces with herself and her anime counterpart.

“Mukbang Moment,” inspired by the South Korean mukbang, illustrates the bastardization of a communal culture of food. The mukbang was popularized in American culture through YouTubers like Trisha Paytas who boast hauls of In-N-Out burgers and fries for her viewers. Wu was fascinated by how the South Korean tradition lost its intimacy through this Western appropriation.

Wu explores the way mukbang videos display women consuming food in an erotic way. In the “Mukbang Moment” piece, Wu offers a mouthful of cake to the audience, a gesture both kind and forceful. Song’s baggy clothing and active interaction with the audience contrast with the anime figure’s mannequin-like quality. The latter’s fixed glance and erotic consumption of food are tailored to the viewer. She is an object, whereas Wu’s portrait is the subject. The painting’s composition is meant to mirror a thumbnail-like YouTube clickbait.

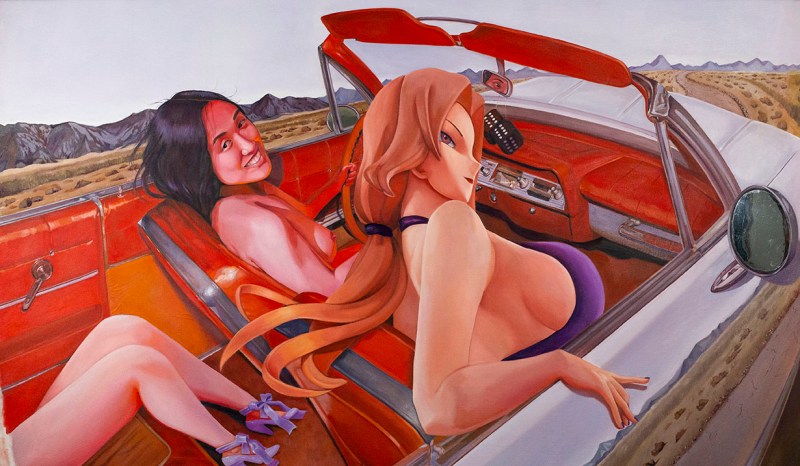

“Fear and Loathing” riffs off of the lore of the American road trip, alluding to the film “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas,” but instead focuses on the complex bond between women. In the film, a pair of male journalists embark on a road trip in a red convertible, doing drugs and speeding through the desert to Las Vegas.

“There’s always this sense of brotherhood and camaraderie that is missing in the world of female media,” Wu told the Daily, deeming it the inspiration for her painting.

The world is constantly mythologizing women, robbing them of the power to direct the narrative. “Fear and Loathing” allows women to mythologize themselves, too. In this take on the American road trip, Wu is at the wheel.

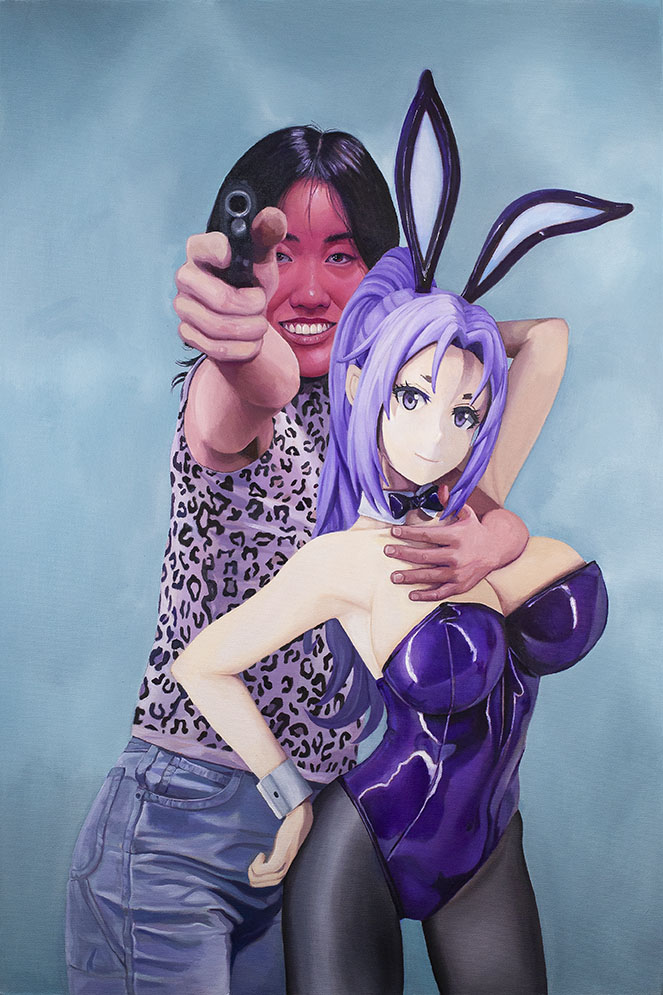

Wu embedded traditional vehicles of masculinity and violence such as a car, a knife and a gun into the works. Wu called the objects “breadcrumbs of desire.” Her painting “Glamor Shot” was inspired by a pregnancy reveal photo she stumbled across, in which an old white man held his pregnant wife’s belly while wielding a gun. America encourages men to be both the savior and the aggressor. To remedy this imbalance, Wu swaps herself in for the man, wrapping an arm around the neck of a curvy anime woman while pointing a pistol at the viewer.

“Glamor Shot” calls into question the relationship between desire and violence. Are women wounding the anime woman through their desire to be her, or are men wounding the anime woman through lusting for her? Better yet, are men wounding women through their desire for the real woman to meet the idealized woman?

The relationship between Wu and the anime girl is ambiguous. “It’s not obvious whether I am the possessor or the protector,” Wu said. The real woman and the fantasy woman seem to have a deeply symbiotic relationship. It is vague whether the anime woman is someone to look up to, lust for or coax into personhood through friendship.

Through the five paintings, Wu defines what it means for her to be an Asian woman in America. The line between “subjecthood” and “objecthood” is blurred in the romanticized Asian woman. The precision of Wu’s painting style makes the viewer feel the grease of the mukbang or the itchiness of a synthetic bikini. The paintings are not about detesting the anime woman, but learning to befriend her. For the artist, the answer to reconciling a relationship with the anime girl, or a constructed, idealized fantasy, is both trying to feel “like you’re not in her shadow” and acknowledging her presence.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.