There is a Chinese idiom that says that some man-made disasters are as bad as natural ones. According to a Chinese student who has chosen to remain anonymous due to potential repercussions for herself and her family, the fire in Urumqi in China’s Xinjiang province would fall into this category.

A fire in an Urumqi apartment building in late November killed 10 people, including children.

The fire and subsequent response from emergency responders sparked wide-spread demonstrations across the country, including in Beijing, the capital. Some in the country attributed the deaths to the country’s “zero-COVID policy,” which includes mass testing, long quarantines, tracking of movement and city-wide lockdowns aimed at preventing the spread of the virus.

Hope and fear are two words the student would use to describe her reaction to the wave of mass protests. Many Stanford affiliates interviewed requested anonymity, citing the risk posed to themselves and their families if they spoke out against the government and its policies.

“The hope comes from… the things you’ve been talking about behind closed doors being said out loud on the streets by your people,” she said.

She said that her parents’ generation was the one that protested in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Knowing that she is around the same age those protestors were who were massacred bears a heavy weight.

The fear comes from knowing that there will be consequences for those who speak out, including arrest and being met with police violence, she added.

As of Dec. 7, China has eased several restrictions, dropping its testing requirements for those traveling domestically, permitting those with mild symptoms to quarantine at home and removing the requirement of a negative test in public spaces.

Simon Luo, a postdoctoral fellow with the Stanford Civics Initiative who teaches a course on contemporary Chinese politics and political thought, pointed out that Urumqi has been under strict government control due to riots that took place there on July 5, 2009.

“Since the July 5 incident… China has been having very strict political control policies in Xinjiang for a very long time, and that’s why… the entrance [to apartment complexes] was limited,” he explained.

The student said that “very unreasonable [zero-covid] policies” have led to deaths in China and she personally has a family member who was unable to receive medical care due to this policy.

The Washington Post shared a story last week of a woman with cancer who was barred from leaving her home and couldn’t gain access to an ambulance. She eventually died in a hospital.

Another Chinese student who has also chosen to remain anonymous due to potential repercussions for his family said that this policy has made it difficult for him and other Chinese international students to return home.

“We’ve been impacted by zero-COVID for three years. During the holiday when other international students are about to go back home, we’re not able to go back home,” he said.

Communications professor and Freeman Spogli Institute senior fellow Jennifer Pan said that protest is not new to China.

“The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to power through revolution. Protest, collective action and social mobilization are nothing new to Chinese society,” she said.

While the zero-COVID policy is the root of these protests, demonstrators also demanded an end to Chinese President Xi Jinping’s nine-year rule and called for freedom of the press and rule of law.

“One of the most striking things about this wave of protest is the animosity directed at the central government and political system,” Pan said. “However, the more pertinent question may be whether protests will fade away if the COVID policies are changed. I don’t have the answer to that question, but it’s the one we should ask,” she continued.

The loosening of restrictions seems to have largely quelled the demonstrations.

Luo is grappling with how to respond to the protests as a member of the overseas Chinese community. “I, myself, feel powerless from time to time,” he said.

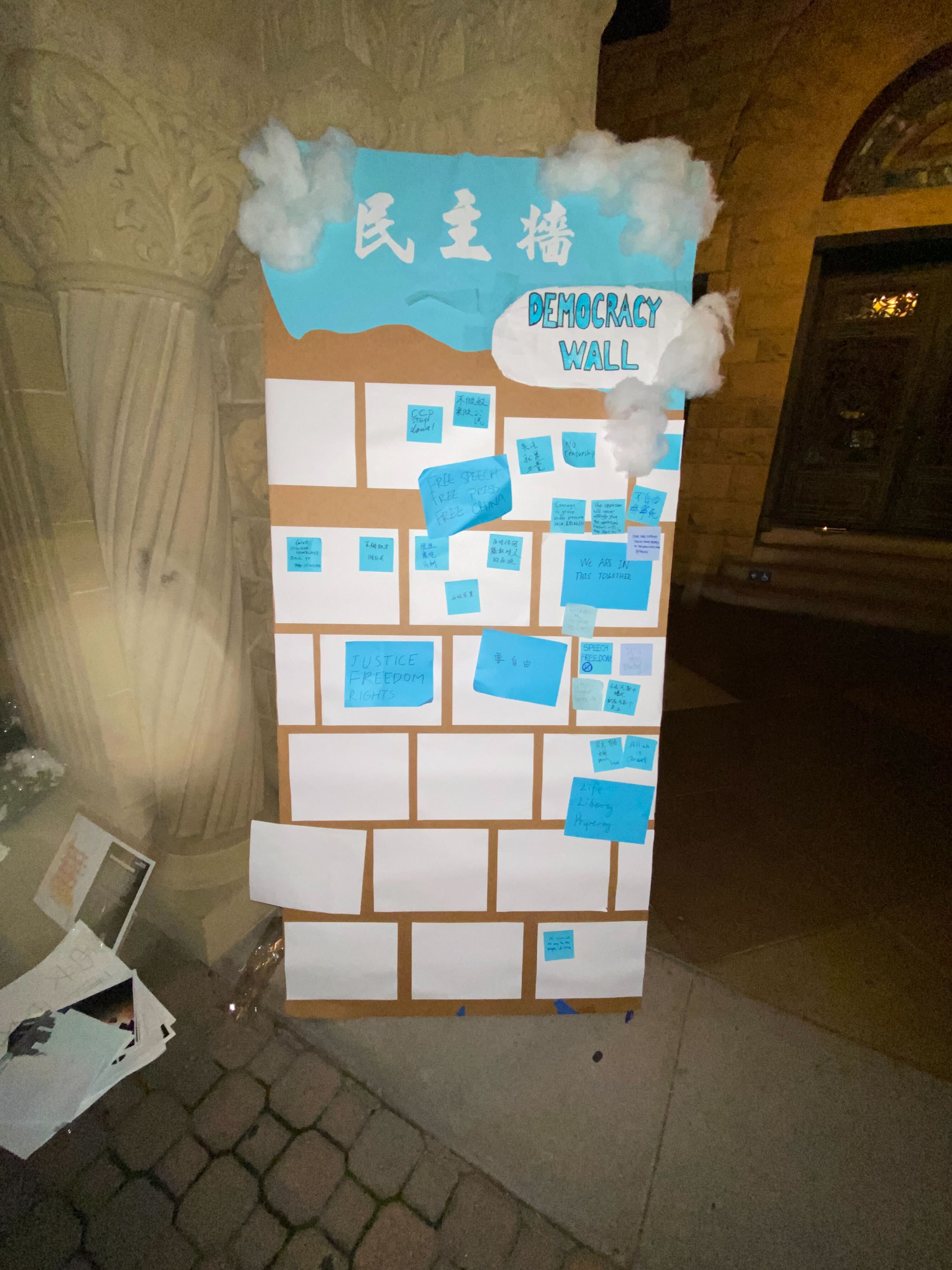

One of the students chose to help organize a vigil for the victims of the Urumqi fire and all those who lost their lives due to the zero-COVID policy.

“Our brothers and sisters, other college students in China, they’re literally standing on the streets to protest against the policy and face police brutality directly. We are in a more privileged position here in the US. We definitely need to do something to show that we’re standing in solidarity with them,” he said.

The other student pointed out that it is difficult for Chinese students with families back in China to take action saying, “There’s an internal battle with ‘what can I do?’”

She said that what she wants to do is clear — protest — but what she can do is limited without facing repercussions. She only speaks about this issue with students she trusts since, according to her, the fear she feels is hard to understand for students who haven’t lived in a totalitarian state. Due to these fears, she has chosen not to act publicly.

“I don’t want to demean peoples’ activism, but this is very different from posting a black square on your social media,” she said. “When you’re going against a totalitarian, very brutal, historically insurmountable state, the kinds of risks you’re taking by even showing up to a demonstration, by liking a post on Instagram is immense,” she said.

Both students hope that more attention will be devoted to the protests. “There are people giving up their lives to bring this information,” one said. She said she hopes that Americans can rally around Chinese protesters as they rallied around Ukrainians, who, she said, have received far more attention. “The least people can do here is just to learn about it.” She also added that those who do not protest should request permission to take photos of those who do as the circulation of these photos could seriously impact them.

The consequences of these protests are uncertain, but to gain a clearer view, Pan looks at the past. She says that following the Tiananmen in 1989 and Falungong protests in 1999, the CCP “strengthened the power of the Ministry of Public Security and China’s repressive apparatus.” She added that “this history suggests that this round of protests, especially if they continue and expand, will likewise affect the CCP, but what those effects will be remains to be seen.”

Luo hopes that American activists choose to learn from Chinese demonstrations. “Social movements are global. There is a mutual learning process about activists in terms of tactics, in terms of strategies, in terms of slogans,” he said.

While scholars try to decipher what the future holds for the Chinese people, one of the anonymous students urged outsiders to focus on the Chinese peoples’ humanity.

“You can hate the CCP and criticize China as a state but within that country there are so many people whose lives are being impacted and they are struggling to survive within a regime that’s oppressive,” she said.

“You have to realize just like in the US the US is not a unitary actor, the US is composed of different people with drastically different life experiences. I wish people could humanize that for other countries beyond the US. Especially China,” she said.