In 1990, Kimberly Carlisle ʼ83 was sent to Moscow as part of her work in ad sales for the Stanford Magazine.

It was an emotional visit, as far as work trips go. The city felt simultaneously familiar and distant, as if she had some indefinable connection to this place she had never been before. And in a way, she did.

A decade earlier, Carlisle was ranked fourth in the world in the 200m backstroke. All signs indicated she was on track to qualify for the 1980 Moscow Olympics.

This was a trajectory she had planned years before with her father, a beloved coach and mentor. Though Terry Carlisle’s own Olympic aspirations had been disrupted by a polio diagnosis at age 17, he remained in the sport, becoming a well-respected coach on the high school and collegiate levels. Kimberly thought the world of him and, while Terry did not get to realize his own Olympic dreams, it looked like she could have a chance at her own.

The sport that the father and daughter adored had done a lot for Carlisle. As a teenager, she had moved to Cincinnati to train with a top club program. She gained admission to Stanford in one of the earliest classes of female athletes to receive athletic scholarships following the passing of Title IX. Beyond the fact that her family could not have afforded Stanford without that scholarship, the symbolic and social gravity of the opportunity was not lost on Carlisle.

“I grew up in a place where women were ostracized because we were smart and athletic,” she says. “It was a watershed change for me to go to a place like Stanford, where we were celebrated, respected, along with all the other talented, unique, interesting people from all different walks of life.”

In someone’s dorm room at Stanford during her freshman year, Carlisle remembers hearing celebratory shouts when the American hockey team beat the Soviet Union (USSR) to win gold at the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York. The U.S. victory was only intensified by the recent Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979. It was around that time that Carlisle first recalled hearing whispers about a potential U.S. boycott of the upcoming Olympics in response to the USSR’s actions.

Before long, the decision was made.

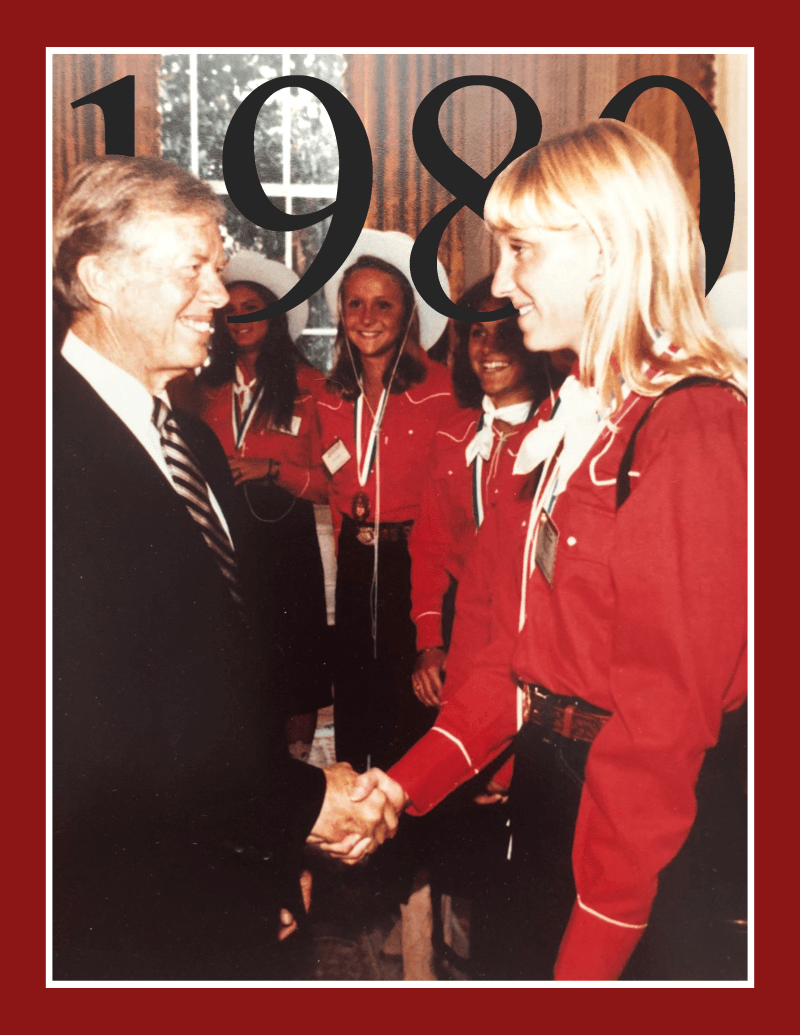

“I can’t say at this moment what other nations will not go to the Summer Olympics in Moscow,” then-President Jimmy Carter told representatives from the American team in March 1980. “Ours will not go. I say that without equivocation.”

That summer, Carlisle swam just as she and her father had hoped, qualifying for the American team. But the group of athletes would never see competition in Moscow’s Olimpiysky Pool, which sat behind a still-intact Iron Curtain.

Right after the trials, the U.S. swim team was invited to Washington, D.C. for a reception and photo call with President Carter. As much as she disagreed with the decision and wanted a chance to compete, Carlisle could see the decision’s toll on the president as he shook everyone’s hand and spoke to each athlete.

“In a way, actually, I aligned with him, to see the larger world and to try to do what we can to make it better,” she says now. “That’s something beyond maybe things in our life that we wished we had experienced, like going to the Moscow Games. But it propelled me to see something larger.”

However, 10 years later, when Carlisle called a cab to take her to the Olimpiysky Pool in Moscow, the lost opportunity still stung, her sympathy for President Carter’s decision having dulled, but not erased, the pain. So many strokes, hours, laps and stopwatches had gone into her stunted Olympic berth in 1980. She hoped a short swim in the pool — the one she would have competed in as a 19-year-old freshman backstroker — would be a step towards acceptance.

***

Chris Dorst ʼ77 MBA ʼ82 credits much of his successful water polo career to being in the right place at the right time. When he first got into the sport at the beginning of high school, his goal was simply to make the Frosh/Soph team.

There was no grand plan to become a collegiate athlete, but Dorst kept improving in the pool, and water polo led him to Stanford. The Cardinal went 0-6 in what was then the Pac-8 during his freshman season. But by his senior year, Stanford boasted one of the best teams in the country, and had won an NCAA title.

As a goalie, “my job was to float and get hit by things,” he says. “I was really good at that.”

His performance in college had not gone unnoticed, and Dorst was selected for the men’s national team. Earning a spot meant receiving T-shirts emblazoned with “U.S. Water Polo.” For Dorst, this was the stuff of dreams. By the late 1970s, it was practically a given that he had earned a place on the upcoming 1980 Olympic team. He had come a long way from his original goal of making the Frosh/Soph team at Menlo-Atherton High School.

At that time, men’s water polo had long been dominated by European countries whose hefty players beat the American teams through sheer size and relentless passing and shooting. The American men struggled with the static game, and had never won an Olympic gold medal. In 1976, the U.S. did not even qualify a team for the Olympics.

But between 1976 and 1980, the shot clock was reduced from 45 seconds to 35. Though at first glance a relatively small change, for the U.S. men, it was anything but. All of a sudden, their style of play — a solid transition game, fast swimming speeds and counter-attacking — was a real threat to teams that had once beaten them easily.

It’s easy to hear Dorst’s pride when he talks about how his team revolutionized water polo, but the competitive instinct he felt as a 23-year-old is present in equal measure. He was in the right place at the right time, and he was enjoying every moment.

“It was fun,” he says. “Because we would just beat the tar out of these European teams in Europe. And their coaches would be yelling and screaming, and their guys would be having trouble climbing out of the water, they were so tired.”

But then the near–fairy tale was interrupted. In March 1980, representatives for the U.S. Olympic team were invited to the White House for a “dialogue” with President Carter. Dorst and Gary Figueroa, one of his teammates, paid their own way to D.C. to represent men’s water polo.

The dialogue was not so much a conversation as an instruction. Carter told the assembled athletes to accept the fact that they would not go to Moscow, and then left his aides to explain the decision. They did so, Dorst says, but took a rather condescending approach when explaining world politics to the devastated representatives. They promised to hold an alternate Olympics, to take various steps to repay the athletes for what this political decision would cost them. None of their promises ever materialized.

The wounds were still fresh a few months later, when the national team’s schedule took them to Copenhagen, Denmark. Hanging out in a hotel room “with a bathtub full of Carlsberg beer,” a teammate floated the idea of chartering a bus and trying to get to Moscow that way. It stung even more when the Soviet team — opponents they had beaten handily in the preceding couple of years — took gold at the Olympics.

“I just wanted to play,” Dorst says. “I just wanted to play against the best.”

Talking about it now, he is taken back to that March day at the White House. After hearing Carter’s decision, reporters clamored for quotes from the affected athletes. Dorst was still reeling from what he had just heard and from the realization that everything he had worked for had been so matter-of-factly dismissed. He was ready to spit out to the journalists, “Those guys are sons of bitches!”

But his teammate, Figueroa, stepped in. “If this is the worst thing that happens to me,” he told the reporters, “I’m the luckiest guy in the world.”

Dorst says now that Figueroa was right, that he could see a future and a context beyond a single Olympics that the Cold War had taken from them. The pair had revolutionized the sport they played alongside teammates they respected deeply, and maybe there were more important things in life. So Dorst let the Olympics go, at least for the time being.

***

In May of the same year, like her future husband, Marybeth Linzmeier Dorst ʼ85 and her aspirations were thrown a curveball. She contracted mononucleosis, a virus that counts fatigue and body aches among its symptoms. The timing could not have been much worse. Her diagnosis came just a couple of months before 17-year-old Linzmeier Dorst was set to compete in her first U.S. Olympic trials.

This was not the only complicating factor for the high school junior. President Carter had just announced that America would not send a team to the Olympics that summer.

Although competing in Moscow was no longer a possibility even if she did qualify, when her doctor recommended she stop swimming to recover, Linzmeier Dorst refused. “Yeah, that’s not going to happen,” she told him. She had put everything into swimming, and did not want to fathom a reality in which this illness kept her from the upcoming Olympic trials.

Instead, they came to an agreement: Linzmeier Dorst could train as long as the intensity was greatly reduced. This meant far fewer yards than usual and laying off training for the long distance events she normally favored, namely the 800m and 1500m races.

Under doctor’s orders, Linzmeier Dorst begrudgingly moved from Lane 1 — where she and her fellow distance swimmers “trained like the animals” with long and intense workouts — to practicing with the sprinters in Lane 8.

“That’s where the sprinters hung out and took a bath, I considered, with the amount of yardage they didn’t do,” Linzmeier Dorst says.

Hailing from Visalia in California’s Central Valley, Linzmeier Dorst had begged her parents to allow her to start swimming in hopes of relief from the area’s intense heat. By the time she was 12, Linzmeier Dorst often had to enter races in older age groups in order to find competition with 13-18 year olds. As she started high school, there was only one other swimmer in Visalia — a boy a couple years her senior — who could keep up with her. To find training partners and continue improving, Linzmeier Dorst would move nearly four hours south of home, to join one of the nation’s top clubs in Mission Viejo.

The bout of mono could have been the end of her 1980 Olympic journey. But Linzmeier Dorst went into the trials with a tenacity characteristic of the tough long distance events she was known for. And, as it turned out, the sprint training she had been forced into because of her illness had an upside after all.

After barely qualifying for the 100m freestyle event, Linzmeier Dorst found that the weeks spent practicing “sudden bursts of speed off the blocks” had made her a stronger swimmer across the board. She knocked two seconds off her previous personal best at the trials — an almost unheard-of improvement — and ultimately placed fourth in the finals, earning a place on the 4x100m freestyle relay.

She finished second to qualify in the 200m freestyle, narrowly missed out on qualifying for the 400m freestyle and qualified in the 800m. And had the Olympics run a 1500m freestyle for women then, Linzmeier Dorst would have qualified for that too. She had had the Olympic trials of a lifetime and posted career-best times, all while recovering from mono.

Linzmeier Dorst is humble as she talks about her performance at the 1980 trials, emphasizing instead her love for the sport and what the experience meant to her. She mentions Michael Phelps as someone who would go to the Olympic trials with the intention of cementing his reputation as the best, but explains that she did not think that way at all about herself.

“For us,” she says, “it was just trying to make the team.”

This humility is characteristic of his wife, according to Chris Dorst. “Don’t let Marybeth soft-pedal you,” he says. “She was the real deal. She’s going to be self-effacing: ‘Oh, I didn’t really, I’m not really…’”

Dorst pauses briefly, before continuing.

“When your name is used in the same sentence as Katie Ledecky and Janet Evans, you’re doing okay.”

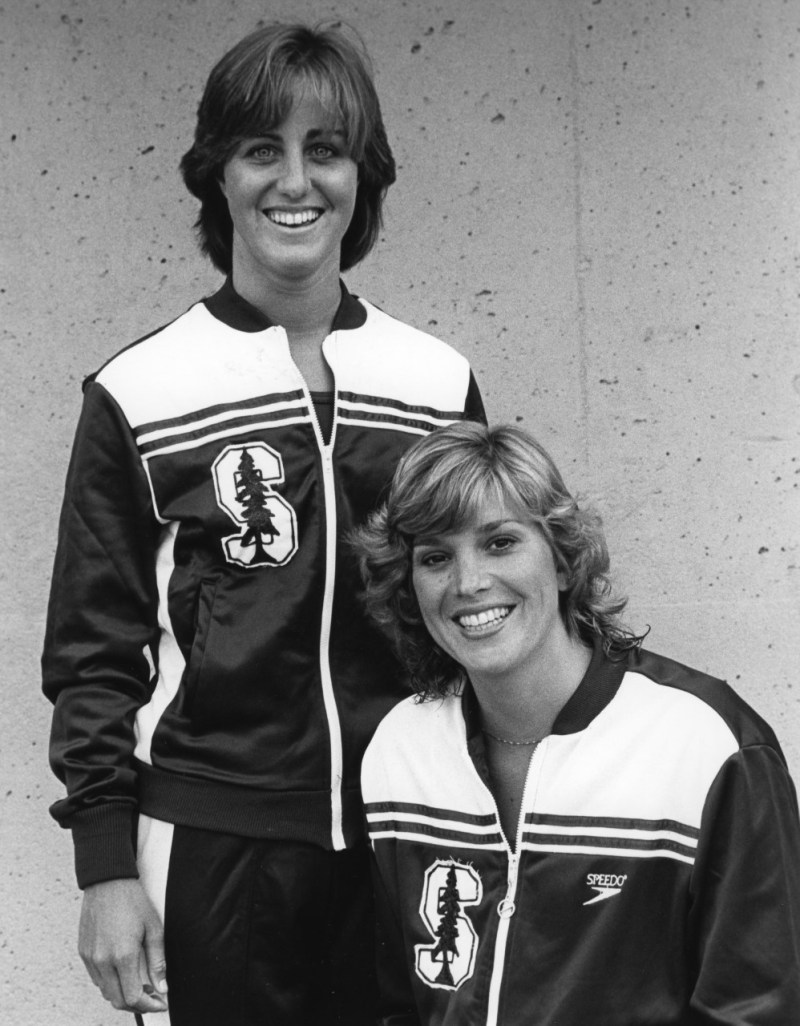

And Linzmeier Dorst was doing better than okay. The next fall, she started her collegiate career at Stanford. And just like the 1980 Olympic trials, she spent much of the next four years leaving few accolades unclaimed.

***

Unfortunately, what Kimberly Carlisle and her cab driver found when they pulled up to the Moscow pool looked very little like what it had ten years earlier, when the venue hosted over 300 athletes from 41 countries not participating in the boycott.

Unkept grass grew through cracks in the sidewalk. Beyond the pavement was an abandoned pool, guarded by chains and padlocks. They could only peer through the glass windows.

The swim she had hoped for was impossible. But seeing the pool provided a kind of closure, a reminder of what the Olympics meant and what the world looked like when its ideals were abandoned. “It was such a poetic conclusion,” Carlisle says. And she has since found an unexpected kinship that helped with reconciling her identity as an individual and an athlete.

It traces back to her early years, when she was just starting competitive swimming. She saw race horses being trained and couldn’t help but notice the parallels between herself as a swimmer and the animals, the way they were paced with stopwatches, put through recovery and valued largely for the times they posted. After their careers are over, Carlisle notes, the horses are often killed, but not before being subjected to terrible conditions.

This drove her to found Flag Ranch, which now operates as a sanctuary for retired race horses. The ranch currently cares for over fifty horses, and soon Carlisle hopes to begin equine therapy programs for trauma relief and other forms of recovery.

Her beloved father passed away in January of this year. Just as they shared a passion for swimming, Carlisle wants to continue the care and dedication he showed towards others. In a similar vein, she still advocates for the Olympic tradition and its power to foster a global community.

“Thank God it wasn’t destroyed between ʼ80 and ʼ84,” she says. “Because I still think it’s a way the world comes together that’s unique and vital.”

***

Chris Dorst thought he was done with Olympic water polo in 1980. But after returning to Stanford a few years later to start his MBA, he began training again. Unfortunately, Dorst and a few of his national team teammates were soon told the weight room was off-limits for them.

This was until George Haines, then the head coach of the women’s swim team, heard that some of the best water polo players in the world were being prevented from using the weight room. He quickly stepped in and invited them to train with his team.

So Dorst and his friends joined the women’s swimming team in the weight room. Together with a few of her teammates, an undergrad named Marybeth Linzmeier started teasing Dorst about how much he could lift. She remembers thinking he was especially cool because one of his teammates, Drew McDonald ʼ77, was dating Kim Peyton ʼ80, a 1976 Olympic gold medalist and Stanford swimmer. And she remembers that they laughed a lot in the weight room. For their first official date, the pair got frozen yogurt at a place “right off of University Avenue.”

Had he gotten the opportunity to compete at the 1980 Olympics, Dorst says, he probably would not have started training again. Which means he and Marybeth may have never connected in the weight room. But returning to Stanford and water polo also led to another Olympic opportunity, this one on home turf. In 1984, the Olympics were coming to Los Angeles.

***

Four years after his unpleasant trip to the White House, Dorst waited to march into the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum as part of the parade of nations. The U.S. team, as per tradition, would enter the Olympic area last as the event’s host country.

When describing the scene almost four decades later, he recalls the hours-long wait backstage in ill-fitting outfits that he did not particularly care for. Dorst actually jokes about how bad the outfits were. That is until he reaches the moment in his story when it was the American team’s turn to enter the stadium. Then laughter is replaced by strong emotion.

“And all of a sudden, you walk down this tunnel, and it gets really, really bright,” Dorst says. He pauses, the memory of that moment returning in force.

“And it’s deafening.”

Chants of “USA! USA!” filled the air. The noise and lights and crowd were all the more meaningful to certain athletes in the stadium, who had come so close to the Olympics four years before. Like Dorst, most of the 12 other men on the 1984 Olympic team had also been on the squad in 1980. And at that moment, he remembers, they were all “bawling like babies.”

Eventually some of his teammates realized that they had to find wherever Michael Jordan was in the sea of athletes if they wanted any chance at getting on TV.

In the following days, Dorst got to play in front of his family, friends and future wife. The U.S. men steamrolled their way through the competition and at the end of the medal round, they had not lost a game. Nor had their final opponent, Yugoslavia.

The U.S. led 5-2 with one minute left, before the Yugoslavian team came back to tie the match and win the gold medal on goal differential. Dorst still relives that game sometimes, and what could have been had there been just one more goal for the American team or one more save. But overall, he is proud of his silver medal and thankful to have been in the right place, at the right time, with the right people. And he will always remember those times and the feeling evoked when he walked into the Coliseum in Los Angeles as an Olympian.

“It was otherworldly,” he concludes. “It was really one of those things you look around and go, ‘I’ll never experience anything like this again.’”

***

Marybeth Linzmeier Dorst had a record-setting collegiate career at Stanford, earning one team, eight individual and three relay NCAA wins. Three of these titles came at the 1984 NCAA Championships.

A few months later, she narrowly missed out on qualifying for the Los Angeles Olympics. It hurt, especially given her dominance at the recent NCAAs and incredible results four years earlier. But Linzmeier Dorst does not want what happened to be spun into something different than it was.

“I don’t want it to be looked at as a disappointment,” she says. “I’ve been interviewed a thousand different times. And you’ll say one little sentence and then they go with that, because they want to sell a good story. For me, it’s more looking at the whole… the whole was a great experience.

“Yes, I would have loved to have had the Olympic music going on while I was standing there on those blocks, but I didn’t get to have that,” Linzmeier Dorst says. “But I did have those Stanford years, and I loved it. And I got to meet my future husband.”

After graduation, she was inducted into the Stanford Athletics Hall of Fame for her contributions to the University and the sport. She and her husband, who serves as the Director of Guest Services for Stanford Athletics, have three daughters. All played Division I water polo, and one, Emily ʼ15, even played on several NCAA-winning teams at Stanford. Linzmeier Dorst enjoys her work in real estate, and the couple still lives near campus.

Looking back on her swimming career, what stands out to her, Linzmeier Dorst says, are the people she swam with, the opportunities she had and the experience of being a student athlete. She is grateful for the meets she was able to compete at, and is proud of her tenure swimming for the Cardinal.

“There was nothing better than wearing the Stanford jacket,” she finishes.