I. Add women and stir

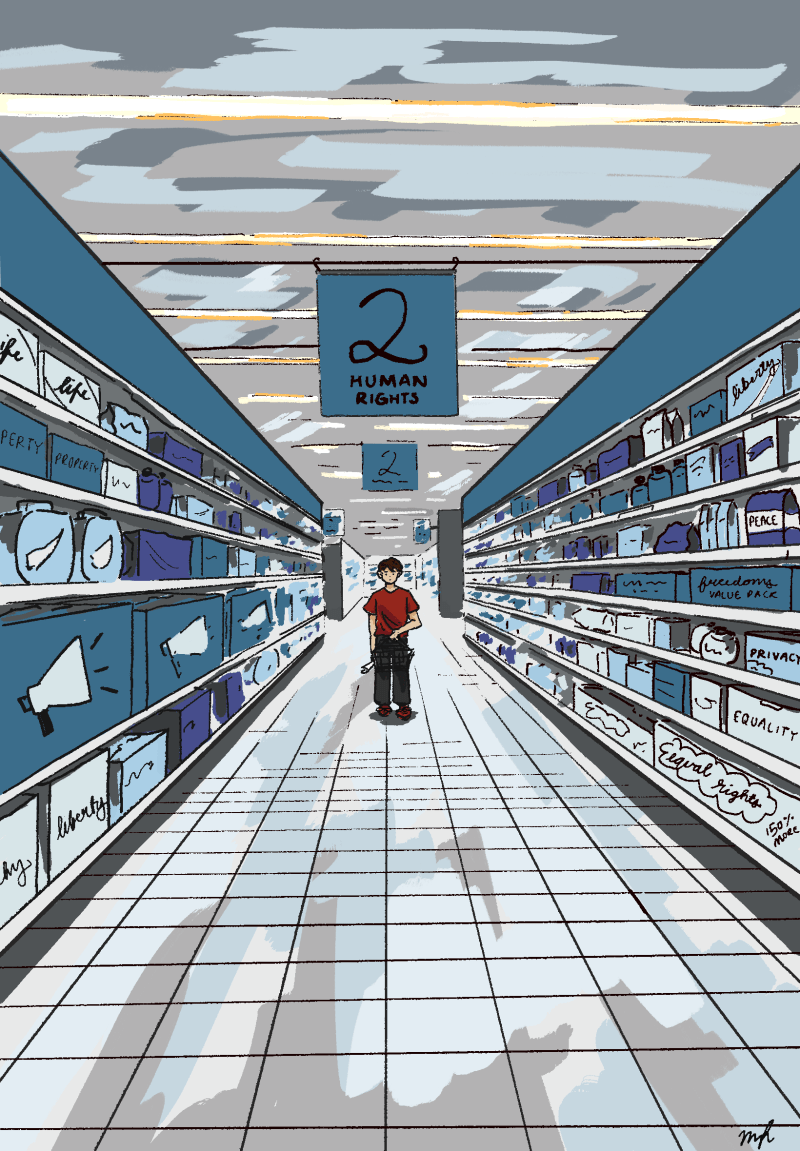

He walks down the aisle of the supermarket, glancing at the recipe to make sure he’s picked up all the ingredients he needs. Eggs, milk. Liberty and equality from the American and French revolutions. Flour, sugar. The relationship between the state and its citizens from Nuremberg. Tomatoes, onions. A bag of mixed rights — life, privacy, check, check — and freedoms — religion, press, check, check.

This recipe is a crowd-pleaser — honestly, no one has ever been dissatisfied. And, excitingly, at the bottom: “For diversity and inclusion, add women and stir.” He beams. He’s discovered universality.

But when she tastes the finished product, she feels sick. She gags on the right to privacy. She sees a Muslim woman from France across the room gag at the same time. They make eye contact only for half a second, but the understanding is complete: they both know that using the recipe to feed more women can only go so far when the ingredients themselves can be poisonous.

Rethink the ingredients, she groans, nauseous. Don’t just stir me in.

(She doesn’t see the Muslim woman gag again on freedom of religion.)

***

“This is why feminism has had to explode the private. This is why feminism has seen the personal as the political. The private is the public for those for whom the personal is the political.”

“In this light, a right to privacy looks like an injury got up as a gift. . . . It keeps some men out of the bedrooms of other men.”

— Catharine MacKinnon, “Privacy v. Equality: Beyond Roe v. Wade”

“A famous philosopher once said to me that he objected to feminist critiques of sex because it was only during sex that he felt truly outside politics, that he felt truly free. I asked him what his wife would say to that.”

— Amia Srinivasan, The Right to Sex

“[T]he doctrine of ‘freedom of religion’ participates in the secular process of defining religion as apolitical. . . . Simply put, the secular state offers individuals freedom of belief, but not the freedom to act publicly based on those beliefs.”

— Lena Salaymeh and Shai Lavi, “Secularism”

***

The one who gagged once

hands him his lunch, waves goodbye as he leaves for work, and now the white picket fence snaps shut and she is insulated (thank god!) from politics and justice.

If the home is apolitical, then political theory by definition has nothing to say on domestic violence. The law has nothing to say on marital rape. Care work goes forever unseen. She remains forever invisible.

The right to privacy, in some cases, can serve as the moat protecting the man’s castle. She wants to scream: Who’s counting how many women have drowned in its waters?

The social contract is a sexual contract. Is that really so radical?

***

The one who gagged twice

notices that they never offer any explanations. They say, “The children will be influenced by the headscarf.” The crowd nods solemnly. “It may incite religious conflict.” Murmurs of agreement. And then they move on.

Freedom of religion always had a funny way of slipping through the folds of her hijab.

They didn’t understand why she was upset. She can believe whatever she wants in private, so why is she still complaining? Just don’t enter your classroom wearing it. For the sake of the students, really. Secularism is really important to us. Anyone who embodies our national values would understand.

Secularism is the crucifix on the classroom wall. Why can’t secularism mean diversity?

***

II. Avoid that aisle

At the end of the week, they run an inventory check. Walking through the aisles, supermarket employees call out what they need to replenish for the next week:

Eggs, milk. Liberty and equality from the American and French revolutions. Flour, sugar. The relationship between the state and its citizens from Nuremberg.

The slave-trade tribunals have been sitting on the shelf for weeks. No one wants them. When customers walk past that aisle, they seem to avert their eyes and walk in the other direction.

Except a Senegalese man paused at that aisle. And a Gambian woman the next day. A couple from Ghana later that week.

They had all been dissatisfied at the end of that Dinner. The recipe left them wanting. They’d thought about his recipe. They knew the supermarket carried ingredients that it needed. They knew he’d probably seen those ingredients too, but had not picked them up.

Had he looked at his feet and shuffled uncomfortably as he avoided the aisle?

***

“[I]t is necessary first, to make the story of resistance an integral part of the narration of international law.”

— BS Chimni, “Third World Approaches to International Law: A Manifesto”

***

The ones who paused

knew that stirring in this ingredient would not be the solution. But it would be a much-needed start.

They’d heard the story. Of how at Nuremberg, good battled evil. International law would now govern how a state could treat citizens, not just how a state could treat other states. This was revolutionary, and they agreed.

But there’s also another story. Of the abolition of the slave trade, the first human rights success of international law. This was revolutionary too.

And it raised questions that the Nuremberg narratives typically did not focus on. What are the roles of corporations and private non-state actors in human rights violations? What are the obligations of citizens in wealthier countries to those in less developed ones?

Questions that disproportionately affected them.

Why don’t we learn from both stories?

At Nuremberg he was undoubtedly the good guy. As he passes the slave trade aisle, the feeling gnaws at him that maybe here he is complicit, in some form, to some degree, however small.

He looks at his feet, shuffles uncomfortably and avoids the aisle.

***

III. Export

Once he’s done preparing several batches of the recipe, he packages them for export. He sends them to faraway places whose backward cultures must need it much, much more than ours here at home.

We’re horrified at honor killings in a faraway country. Yet we refuse to talk about domestic violence at home.

We fear that an arbitrary Muslim man may be a terrorist. Yet we refuse to acknowledge that terrorism can have — and has long had — a white face.

Human rights violations happen everywhere. Just ask minority communities in liberal democratic states who walk by statues glorifying Confederates and colonizers every day.

Look around, yes, but also look within. Instead, we look at our feet, shuffling uncomfortably.

***

“Countries such as the United States, with its muscular military arsenal and monetary strength, are able to export the dark side, push it out of the ranch, sending it in the contemporary moment to places like Guantanamo, Iraq or Abu Ghraib.”

“This dark side is intrinsic to human rights, rather than something that is merely broken and can be glued back together.”

— Ratna Kapur, “Human Rights in the 21st Century: Take a Walk on the Dark Side”

***

The ones who gagged and the ones who paused

have no interest in scrapping human rights. At the end of the day, human rights are all we have.

But they’re reminding us that while expanding our current set of rights is necessary, it’s not enough. They’re reminding us that we cannot take existing rights at face value. They’re reminding us that the stories we tell shape our priorities.

They’re reminding us of the ones who did not gag at the dinner table or pause at the supermarket, but who convulsed alone, out of public view.

The central paradox of human rights thinking is the Other, a lesser human, a non-human, not created outside of rights discourse but through it, as a very function of it. Inclusion and exclusion construct each other.

Jekyll and Hyde, emerging from a violent stew of racism, imperialism, patriarchy, war, but with the powerful promise of a brighter future. For the first time, humanity is united in international human rights law, and the optimism is thrilling. Building a universal recipe is a noble and necessary aspiration.

Adding and stirring without questioning the ingredients and avoiding aisles that make us uncomfortable are too easy. They may seductively promise universality, but it’s an empty promise. Universality cannot mean commonality, non-discrimination cannot mean irrelevance. Intersectionality transforms the premises on which rights are realized or violated. Intersectionality transforms social structures. Universality means intersectionality.

“Yes I know. But . . .” is too easy. We must work harder.

***

IV. What if

“Critical pedagogy seeks to transform consciousness, to provide students with ways of knowing that enable them to know themselves better and live in the world more fully.”

“The classroom remains the most radical space of possibility in the academy.”

— bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom

***

What if every undergraduate’s college experience involved emancipatory political theory — such as feminist, queer, critical race and decolonial theory — whether featured in general civic education requirements or embedded in every degree program?

What if intersectionality was the foundation of every course, rather than just one type of analysis among many?

What if universities encouraged students to challenge the violence of the archives, and to understand that refusing to actively do so is a political decision?

What if universities did not just socialize students into the status quo, but instead invited every student to reimagine the world around them, in order to dream?