“Bob is gonna be difficult, deliberately… Mick is a good gossip, witty, reluctant to spill too much… Bruce loves to talk.”

If he couldn’t play music, Jann Wenner knew he had to be a part of it. He did so by writing rock into history.

Wenner, founder of Rolling Stone magazine, visited Stanford last Wednesday to discuss his new memoir. Communications professor James Hamilton spoke with Wenner about everything from morning feasts of orange juice and LSD, to the postwar baby boom, to the publication’s adaptation to the internet.

“Like a Rolling Stone: A Memoir” recounts Wenner’s memories from an artistically prolific, politically charged era. He wrote the memoir to contextualize his personal life within Rolling Stone’s pioneering work.

As people funneled into the John A. and Cynthia Fry Gunn Building, the nostalgia in the room was palpable. The event primarily gathered lapis-lazuli-wearing 70-year-olds who’d grown up alongside Rolling Stone; peppered throughout these silver heads were a few romantic students who could only dream of the wonder years of rock. They soaked in the knowledge and lived experience of those around them, almost by osmosis.

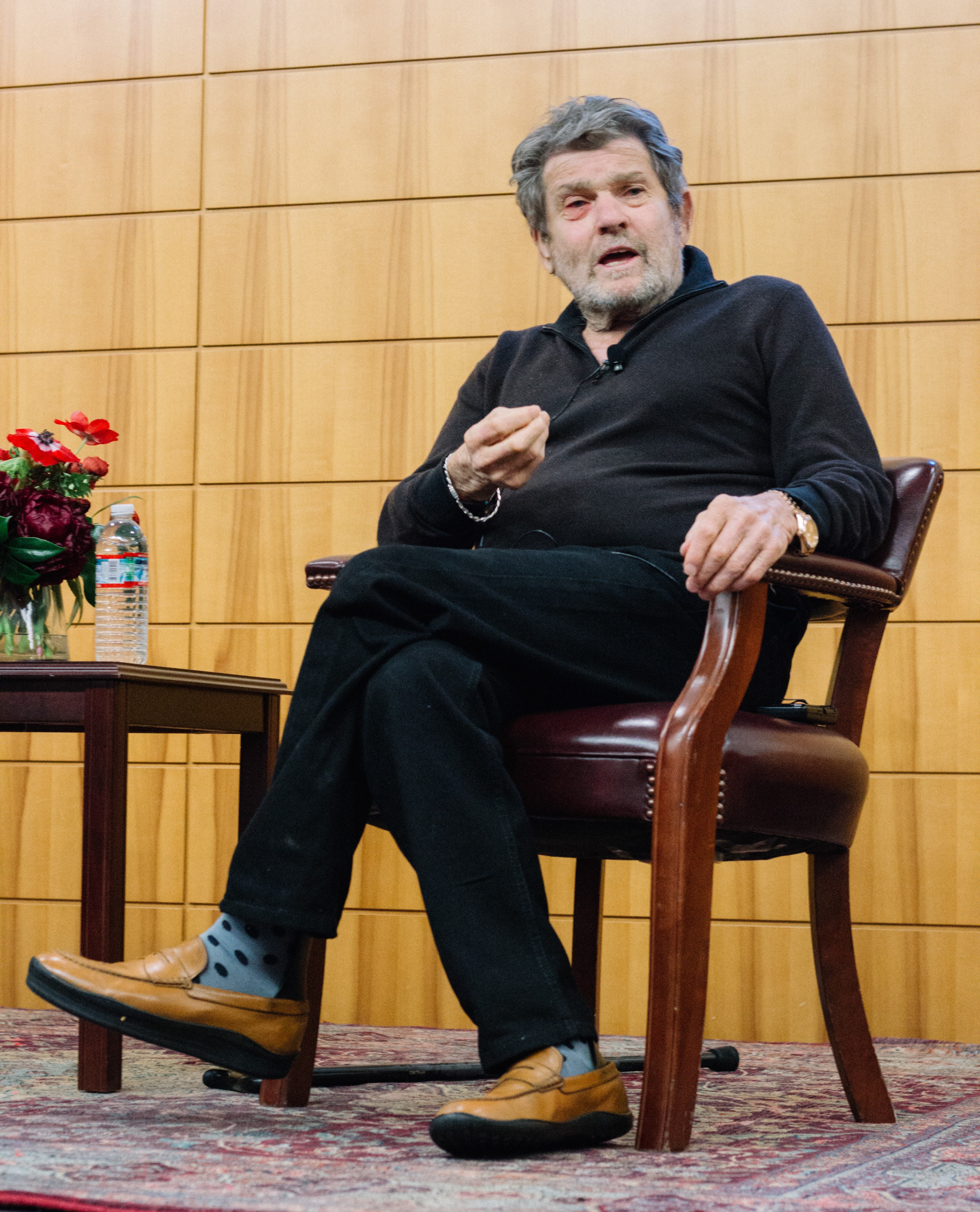

With a cane by his feet and a pair of polka dot socks, Wenner recounted his successes, mishaps and shuffled through a pocketful of chronicles. His trademark dry humor (punctuated by an occasional smoker’s cough) kept the audience laughing, guessing and cupping their ears at every turn.

The magnate was raised in Marin County, which he considered an “ideal American suburb.” He grew up when the Bay Area served as a playground of the Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and others as they brewed up psychedelic-fueled rock.

Wenner co-founded Rolling Stone in 1967, dropping out of UC Berkeley at the age of 21. Hamilton suggested that “successful entrepreneurs see what’s valuable and missing, and set out to deliver it.” Wenner shaped the zeitgeist by locating a human desire for connectivity over art.

“We were all in love with rock and roll. We were rock fans not only because it was joyful, but because it meant something and stood for something,” Wenner said. Established around an obsession with music, the magazine anchored subcultures in a journalistic platform.

Wenner stressed that magnifying politics through the lens of music and literature has always been central to the magazine’s ideology. He mentioned the magazine’s involvement in taking on drug laws, climate change and gun control.

Along with euphoria of the ’70s came deep sadness and death — John Lennon’s 1980 assassination made the world stand still. Annie Leibovitz shot the last ever photograph of John Lennon, his body curled up around Yoko Ono hours before his death. The image appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone soon after. With musical resonance as a driving force, Rolling Stone’s push for gun reform began as a way “to make sense of the death of John.”

Wenner theatrically delivered anecdotes about the luminaries of his day throughout the talk. With a deep understanding of the stars and an all-access pass to their antics, he was the lubricant for storytelling. “The writers you nurtured and edited generated iconic books,” said Hamilton, referencing Hunter S. Thompson’s “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” and Tom Wolfe’s “The Bonfire of the Vanities.”

Wenner disclosed that he is in the process of collecting the seven major interviews he did into a book, alongside an audio book of the original tapes. The audience exclaimed at the prospect of an anthology, which could bring life to the memories of a precious era.

Reflecting on triumphs and mistakes, Wenner recounted the magazine’s sincere reporting and consequential mistakes. One major innacuracy that he talked about was the magazine’s coverage of a 2014 UVA “rape.” The story was proved to be false, and the publication was found guilty at trial for defamation. This series of events ushered in discourse about reporting in the age of the internet.

Wenner voiced concerns about the spewing of misinformation. He brought up Section 230, which allows immunity for third-party websites and is set to be reviewed by the Supreme Court next month. Wenner advised aspiring journalists to prioritize honesty. He encouraged young journalists in the room to “go out, meet people… get facts.”

Wenner did not elaborate on personal matters in his discourse with Hamilton. Prior to the memoir, Wenner had commissioned several biographies that met contentious fates — most notably, biographer Joe Hagan’s 2017 book “Sticky Fingers,” which uses a stockpile of interviews to paint a picture of Wenner’s psyche and temperament. While the editor touched on such topics of past drug use and sexuality in his memoir, on Wednesday, Hamilton and Wenner stuck to the lore of cherished rockstars and journalism.

Jann Wenner was at the epicenter of one of America’s more treasured moments, crystallizing culture as life-sustaining through Rolling Stone. For younger generations who know rock through biopics and archive Instagram accounts, the great stars occupy a realm of fantasy. Wenner is anything but oblivious to the cultural shifts since his heyday — in his eyes, a modern adolescent’s encounter with the Rolling Stones would be like “gazing at the cast of Star Wars.”