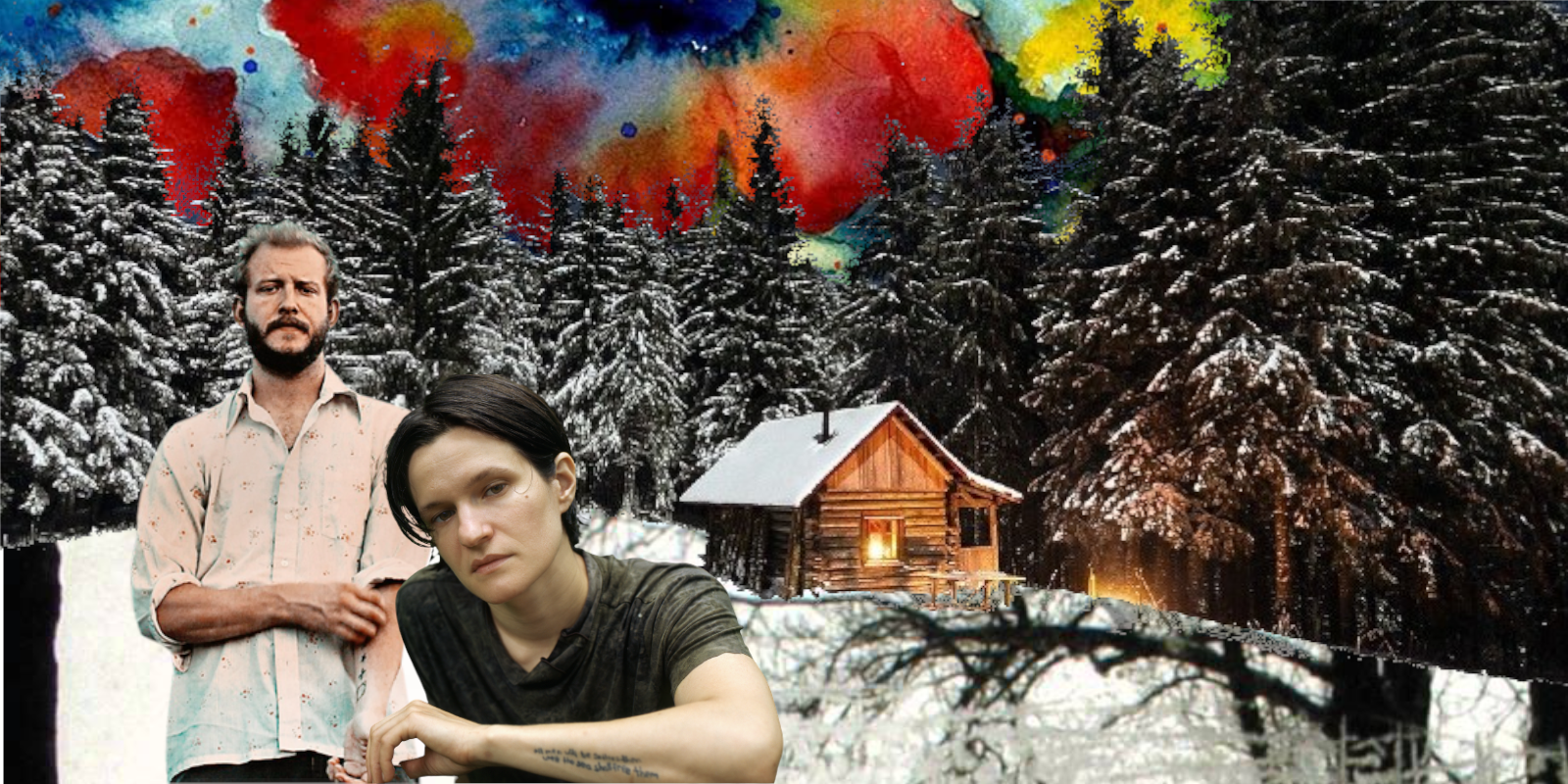

In “Music that Makes You Feel,” columnist Sam Waddoups ’23 recommends albums that take the listener through a specific emotional journey. This week, he covers two albums shaped by loneliness: Bon Iver’s “For Emma, Forever Ago” and Adrianne Lenker’s “songs.”

It’s a story that launched one of the biggest indie acts of the 21st century.

Justin Vernon, a flannel-clad 25-year-old from Wisconsin, had his heart broken at the same time he contracted a string of diseases that left him bedridden for months. So he drove through the night to his father’s hunting cabin, both “to take some time and do nothing” and process the painful failures of his life. After weeks of drinking beer and chopping wood, he started to write music. With the materials he had on hand — a guitar, an old Macintosh computer, and a four-track recorder — he made an album titled ”For Emma, Forever Ago,” under the name Bon Iver.

All contemporary reviews of the album start with that story. It gets repetitive and vaguely mythological: cultural narratives of the castaway, the hermit philosopher and the return to nature all collide into one perfect indie folk legend.

When you listen to the tracks, though, you understand why people tell the story. It’s an album that perfectly captures a specific place and time; its whole emotional tone is explained by that lonely winter in the woods. The lyrics are bizarre, filled with patchwork imagery of beauty and violence. In the album’s best-known song, the yearning “Skinny Love,” he sings, “My my my, staring at the sink of blood and crushed veneer.” On the opener “Flume,” the chorus goes, “Only love is all maroon / Gluey feathers on a flume / Sky is womb and she’s the moon.” The words are ethereal but fleshy, evoking the feeling of watching the viscera of nature right outside your cabin window.

However, the problem with mythology is that it’s not true. Vernon had some buddies over to record the horns on “For Emma,” and his dad’s hunting cabin had a TV. The escape to nature didn’t really exist.

Still, myths have explaining power, which is what’s important: the album tells us that we want our loneliness to mean something.

At the end of the song “The Wolves (Act I and II),” Vernon repeats the phrase, “someday my pain,” yearning for a purpose for his isolation. The music provides it. It’s not that suffering is justified by the art that comes from it but that the music brings out textured feelings that help to process it.

Although the album was made in isolation, Vernon layers his voice so richly that the vocal track is a thick woven blanket, such as the opening harmonies of “The Wolves (Act I and II).” Even on tracks that would normally feature just a single melody track, like “Blindsided,” he multitracks multiple vocal layers, resulting in doubled and tripled falsetto voices. You might expect it to come off as a cold echo, but it provides company, texture, and warmth.

By the end of the album, solitude becomes peace. In the track “Re: Stacks,” the aching lonesomeness of earlier songs is abandoned in favor of complex but comforting construction. “This is not the sound of a new man or crispy realization,” he sings. “It’s the sound of the unlocking and the lift away.”

* * *

There’s one album, though, that executes this balance of loneliness and peace even better. It has an even barer production than “For Emma, Forever Ago,” creating a more spare atmosphere that gives the listener space to think and feel. The simply-named “songs” by Adrianne Lenker was written in a one-room cabin as spring dawned in Western Massachusetts. It’s an album so quiet that you can hear the creak of a wooden chair, the sliding of steel guitar strings and the drip of rain outside the window.

Lenker described her one-room cabin as resembling “the inside of an acoustic guitar.” The guitar arrangements are intricate, churning and tinkering, and the listener feels right up against the strings. Songs like “my angel” and “come” leave you sitting with pensive guitar instrumentals for over a minute before the voice begins. The sound design replicates the cabin: it’s idiosyncratic and enveloping. It uses paintbrushes on guitar strings for rhythms, and the sound of wind chimes, tape machines and rain in the background of tracks.

These sounds are so rich that Lenker doesn’t need a mythological story like Bon Iver—the characteristics of the album itself suggest both its isolation and its closeness to the world.

Lenker’s voice is vulnerable, shaking and honest, performing both fast-moving poetic lines on “anything” and long drawn-out phrases on “come.” On the first side of the album, her voice is doubled or tripled, but in the final tracks, it is bare, left alone with the guitar. This loneliness is not claustrophobic or insecure, but comforting in its intimacy.

Lenker’s lyrics inhabit moments of vivid life rendered beautifully. In “anything,” she sings, “Skin still wet, still on my skin / Mango in your mouth, juice dripping.” Lenker contemplates human connection — “anything,” “not a lot just forever” and “dragon eyes” are some of the most tender and yearning songs about love I’ve heard — but the album also explores the natural world and metaphysics. “Everything eats and is eaten / time is fed,” she sings on “ingydar”.

In the frank and lyrical “zombie girl,” Lenker questions the idea of loneliness:

“Oh, emptiness / Tell me about your nature / Maybe I’ve been getting you wrong / I cover you with questions / Cover you with explanations / Cover you with music”

As the track ends, the room fills with soft sounds: a bee’s buzz, a chair creaking, a tape clicking shut. Emptiness, the album reveals, is not what it seems. An empty room can become a hollow guitar, home to resonating sounds that both excavate and fill the soul. Emptiness doesn’t need to be covered with music; it is music itself. As Ocean Vuong wrote, “loneliness is still time spent / with the universe.”

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.

A previous version of this article incorrectly attributed the graphic to MICHELLE FU/The Stanford Daily. The Daily regrets this error.