This article includes references to death, gore and violence.

They lowered a projector screen above the stage, and a montage started up, bright and loud. Cars sped and crashed across the screen, one fading into another. Disembodied narrators floated in, previewing the accidents.

“Nowadays, her father and I take turns wheeling her around…”

“You can imagine the sound — plastic cups and bodies hitting the car.”

Hissing cymbal and bass synth faded out, and a title rose up. Basic Driving Precautions.

I took Driver’s Ed one January in a small, full SUNY auditorium. The instructor was Chiara, an Italian Jerseyite in her 30s in ocelot jeans and big sunglasses which always stayed on. She liked to comment from her seat on the behavior of the cautionary-tale victims in the videos.

“Idiot,” she whispered loudly to the silent auditorium, when the ultimate fate of mascara-wand-girl was revealed. “And look at that glass eye too. Girl, match the colors…”

I looked back from my seat. Nobody reacted. Everyone was very high or daydreaming. But the movies worked on me. I had bought the cruel logic and was mulling it over. A good person makes a stupid mistake, things collide at huge speeds, someone is crippled for life or destroyed altogether. The driver is no longer good and is now tortured and seeking redemption. The driver, or victim, sometimes one and the same, speaks to the camera from a state of terrible incompleteness. If I’d only known…

At the time, I had few friends in Driver’s Ed or elsewhere. I was interested in intellectualizing the class as far as I was capable. This would serve the dual purpose of entertaining me and assuring myself that I was indeed the best of the thirty sleepy teenagers. The coping logic of one cyclist-killer interested me enough that I still bring him up.

A cyclist had lost control and rolled from his bicycle path, down a steep hill, and into the freeway at high speed. The driver, an extremely normal twenty-something man, had less than a second to react at seventy miles an hour. It could just as easily have been the next car. But he described the accident as a profound turning point. He realized, as the cyclist died, that he had been “delinquent and worthless” for his entire life. He needed to stop drinking and divorce his wife.

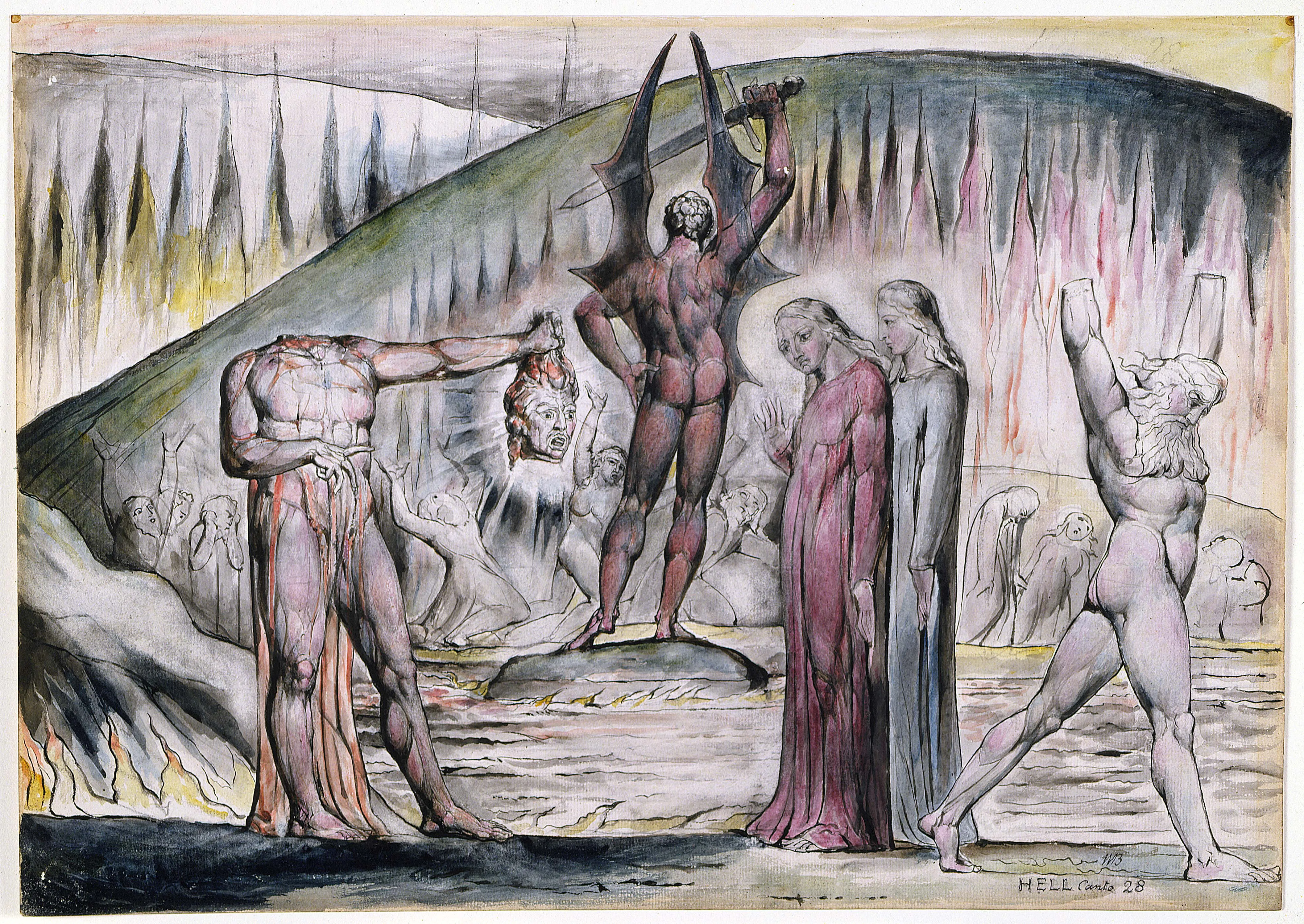

Was he drunk in the car? Was his wife there? Neither. But the manslaughter sentence was not enough — that life he had lived, in which a human could be thrown haphazard under his wheels, had to be itself sentenced and repudiated. The man he used to be could hit a biker, sure, because this was a bad man, with a vague complacency made tantamount to malice — a pilgrim in his Dark Wood. Not this new man, clean-shaven, interviewed in a satiny suit and tie, beside a new wife, with whom he had two new children.

This kind of analysis satisfied me — I was prepared for the ethical acrobatics, which, it appeared, were the main problem of the open road.

The driving instructor who took us out in the afternoons was a retired teacher from Yonkers. He was extremely harsh. The plastic Virgin hanging from his rearview would spin and unspin whenever the car made a turn, which perturbed him and spoke to your inferior character. He kept a full glass of water in the cupholder to watch intently when you came to a stop sign or a red light. If any sloshed out, he’d raise his eyes slowly to you like you’d cut the patient’s aorta.

“That’s a mother of three, that’s a girl on her way to school. They are under your wheels now, congratulations.”

One day this happened, and I nearly cried. I felt for the first time that I was speeding toward death, the water escaping onto my lap the scarcely-contained fluids of a whole full life.

That same day, we had discussed the story of Bruce Kimball, a 1984 Olympic Silver medalist in diving, who crashed into an outdoor party while blacked out, killing two teenagers and injuring several more.

His face began the video, smiling and handsome. Then it flashed demonic in a photographic negative, and an apprehensive drumline started up. Chiara whispered to her assistant teacher, who paused the video as she mounted the stage.

“This one is crazy you guys. If you need to leave, you can leave. My parents saw this on the news when it happened … Imagine that, though … Beer pong, la-la, fun with your friends, and then boom, legs in the air. Some random girl’s like … leg stumps. In the air.”

The assistant resumed the video. Its drums ushered Chiara out like an awards show. With her seriousness and pity there were also always also signs of pleasure — a bouncy step or trancelike gum chewing. She knew she held a powerful thing over us, the untrained. She held up proudly the full bestial gore of the living, driving road.

Sometimes the videos had morals: Be careful near bike paths. Don’t text and drive. Park before applying mascara. Other times the takeaway was simply the wild danger of the great wide world. Just stay in your car.

A young man in Attleboro, Mass., exiting his Honda after flagging down a Ram 1500 for cutting him off, received a crossbow bolt through his carotid artery.

The particular design of the bolt was the thing of greatest interest to the documentarian. It was a rear-deploying broadhead bolt, spring-loaded. A 3D model spun on the screen, in front of a crosshatched blueprint background. What appeared to be a typical triangular arrowhead actually contained spring loaded razor blades which deployed upon impact, fanning out in diagram like a viper’s jaw. The design maximized the bolt’s “artery-slicing diameter.” We were all rapt.

The young man died on the dark shoulder of the highway, with other cars zipping by. The murderer, an ex-deacon deer hunter, spoke to us from a secondary care facility, with a permanent daze and cataracts. All he could remember from that night, he said, was red-hot rage.

Even Chiara seemed to finally feel the gratuitousness of all this when she looked up and saw heads raised for once, tittering. On screen, the bolt was still spinning, deploying and re-sheathing; the narrator discussed how common these devices were, how a hunter will know the crucial anatomy. She dismissed us for the day.

At the end of class we would stand shivering in clumps in the parking lot, waiting for rides and squinting at one another. Chiara would wave at us without looking and pull away in her Chevy truck. One evening, near the end, I realized I did know one person in the class. A girl who’d been expelled from my middle school years before: Kelly. I had known her well. She was a cruel truth-teller, a bully for sure but sharp and comic, which I always appreciated. The other kids had predictably flocked to her meanness. I remembered that I had felt her expulsion unfair.

I greeted her tentatively. I was afraid of the truth of her narrative: another girl went home crying after being called a lesbian or obese, and Kelly was sold out for that and much worse by her peers during a blown-up investigation. It was a showy exorcism after which the school psychologist prescribed lots of healing.

But she greeted me without surprise. Maybe she had already seen me. She had a strange, wounded sweetness, and commented that I had ditched my long hair. The reunion was somber and adult, asking after each other’s families. We had to speak closely to hear over the wind.

Her thinness, which other girls had spoken of in those years with reverence and disdain, had become severe. She did not strike me as anything but a small animal; her collarbones exposed and red. I kept waiting for her to rupture, for a crossbow bolt to spring through somewhere. I felt with clarity that there was really no one who was going to protect her in life. She was shrewd, though — we both were. We might make good drivers.