In “Music that Makes You Feel,” columnist Sam Waddoups recommends albums that take the listener through a specific emotional journey. This week, he covers two albums shaped by vulnerability: Keaton Henson’s “Birthdays” and Sufjan Stevens’s “Carrie & Lowell.”

Singing in a whisper is technically impossible. When you whisper, you halt your voice’s vibrations so that pure air can pass through with just the sound of a breath. No musical notes can be produced in a true whisper.

However, musicians try anyway. To do it, you start with the smallest vibration your voice can muster. Then, you empty your lungs to surround the note with a rush of air, letting it scatter throughout the volume of breath. A whispered song is a vulnerable act. You reveal your most unbridled breath, your deepest source of life.

***

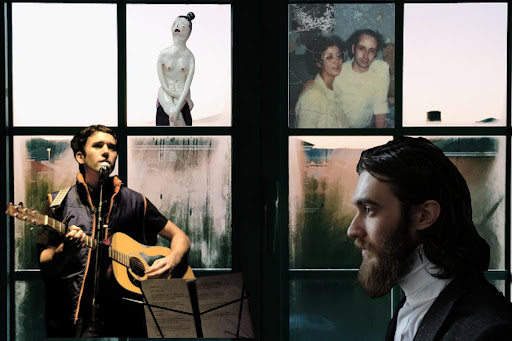

Keaton Henson’s voice is so quiet that, when he plays live, you can barely hear him from 10 feet away. But you won’t find him playing often: he experiences severe stage fright and prefers to stay alone inside. In 2012, he played concerts designed for one person at a time: he projected a live performance into a small dollhouse, and one at a time, fans stuck their head in to watch him play.

“Perhaps you’d like me more if I was in a band,” he sings, “but you know the crowds unsettle me.”

This intense privateness, though, fits the closeness and intensity of his music. His albums play like confessions and scrawled notes of unrequited love.

His second album, “Birthdays,” is tender and yearning. On most tracks, he plucks a muted electric guitar as his voice breaks and pleads. The strings of the guitar sometimes rattle in the imperfection of spontaneous emotion.

He lays bare the insecurity and sensitivity most people are reluctant to express. In “Lying to You,” a song of unspoken deception in a relationship, he sings, “I’m just as damn disappointed as you / only I just do better to hide it.” In “10am Gare du Nord”: “Please do not hurt me, love, I am a fragile one / and you are the white in my eyes.”

While the lyrics might seem plainly melodramatic in isolation, they pierce into your brain as you listen. They become your own private thoughts and your own needing, pleading self. There is no pretense or guard to his voice, and that plain openness allows the over-the-top lyrics to come across as sincere and necessary.

The album is a case study in confronting our deepest self and letting that out into the world, even if it creates a trembling fear. Henson is vulnerable in his approach to himself and his art, breaking the listener’s heart wide open.

***

Whereas Henson’s brand of confession in “Birthdays” uses universally applicable phrases that allow listeners to hear the words as their own, Sufjan Stevens takes a different approach in his 2015 album “Carrie and Lowell.” It is full of startling and enigmatic details.

The album’s specificity is rooted in its personal origin to Stevens. The titular Carrie was Stevens’s late mother, who was an inconsistent parent and died in 2012. Lowell is his stepfather, whose marriage to Carrie marked a period of happiness in Stevens’s life. The album retreads both bittersweet and traumatic childhood memories and ponders the death of a complicated parent. Stevens described his mother as an incarnation of his musical sensibility: “deep sorrow mixed with something provocative, playful, frantic.”

His first albums, “Michigan” and “Illinois,” used quirky rhymes and idiosyncratic instrumentation to wax poetic about eccentric state histories. In “Carrie and Lowell,” however, he leaves behind all his twee tricks to confront his past and his reality. The result is an unshakable and searching vulnerability.

Stevens’s voice carries a light falsetto breathiness that quivers but refuses to break. Although, like Henson, his voice is burdened with apprehension, it never feels heavy in the same way. In “The Only Thing,” Stevens’s voice flies and warbles as he sings, “Should I tear my eyes out now? / Everything I see returns to you, somehow.” It is the voice of a man adrift in memory, processing his grief in real time. Even still, the song is never weighed down from his trauma: the beauty and lightness of his voice creates a vulnerability that cannot be dragged down.

Each song is woven thick with evocative but indecipherable detail. Tapestries of colors, references to Stevens’s childhood summers in Oregon and allusions to myth and religion all interact on the same plane. The result is expression that evades simple description, binds wonder to horror and casts everyday memory in grandeur. In “My Beloved John,” for example, Stevens sings:

“Such a waste, your beautiful face

Stumbling carpet arise

Go follow your gem, your white feathered friend

Icarus, point to the sun.”

The line-to-line connections follow an emotional logic rather than a narrative one. In this thicket of emotion, each song could threaten to blend into the same tone. But Stevens’s soundscapes are greatly varied: the plucked brightness of “Should Have Known Better” contrasts with the expanding cloud of sound in “Fourth of July” and the cathedral-like echoes of guitar strums in “All of Me Loves All of You.”

Stevens puts his heart on display, in all of its confusions. He asks what nostalgia feels like when your past is knotted and your present is uncertain: “Remember I pulled at your shirt / I dropped the ashtray on the floor / I just wanted to be near you,” he sings in “Eugene.”

At the end of “Fourth of July,” the album’s most expansive and haunting track, Stevens repeats a truism between pauses: “We’re all gonna die / We’re all gonna die / We’re all gonna die.” On the track, this truth neither comforts nor despairs, but sits in between the two, with Stevens creating space for it to simply be.

Vulnerability is easily mocked. Honest and tragic lyrics can be derided as melodramatic and self-indulgent, sensitivity as pathetic and wonder as over-sentimental. But we must admire the part of us that returns to sincere vulnerability: the part that trusts another person with our secrets, that respects humanity’s deep and sometimes shameful feelings, that sings in a hushed whisper just for you to hear.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.