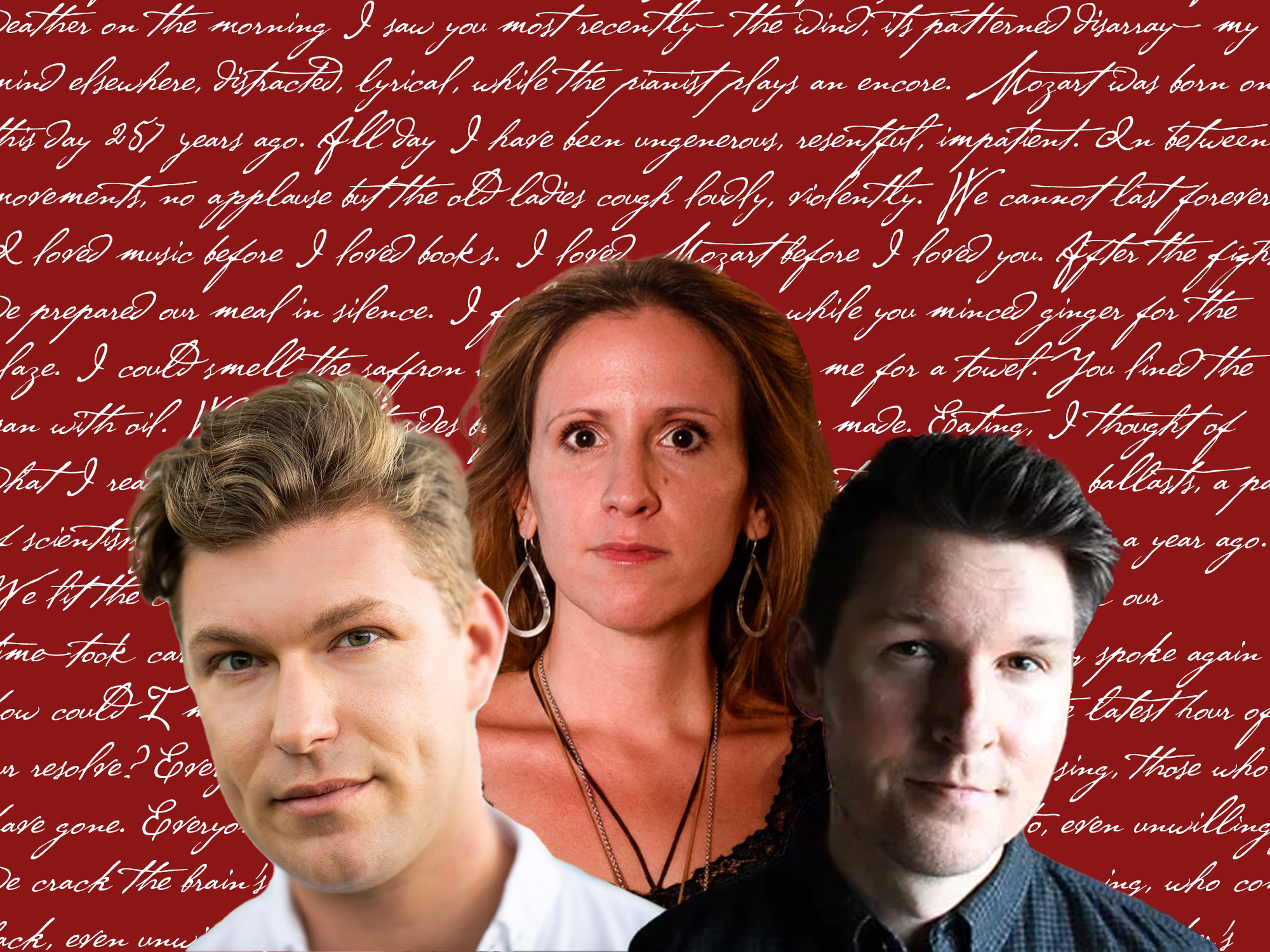

The Stanford Daily sat down with three recipients of Wallace Stegner Fellowship and current Jones lecturers in Creative Writing to discuss their poetry collections, experience and insights gained at Stanford. These interviews have been slightly edited for clarity.

Richie Hofmann

Hofmann is the author of poetry collections “Second Empire” and “A Hundred Lovers.” At Stanford, he is currently teaching ENGLISH 92L, which is focused on analyzing and writing poems of love and sexuality.

The Stanford Daily [TSD]: You wrote about love and attention in your intimate poetry collection “A Hundred Lovers.” How has your narrator’s voice changed since your first collection, “Second Empire”? Was it driven by your internal changes or your aspiration for a new form and more naturalistic depiction of love?

Richie Hofmann [RH]: I would say that it’s a combination of both. A lot of the changes in my poetry and how the speaker was situated in these poems came from changes in my own life — from growing up, being haunted by different fears and fueled by different passions. At the same time, I have an interest to change artistically — to challenge myself and to expand my notions of what the voice in poetry could accomplish.

TSD: At Stanford, you teach the course ENGLISH 92L: Poems of Love and Sexuality, where you discuss shifting attitudes toward sex and gender. Can you tell me a little more about the curriculum?

RH: It was really interesting to me to think about how stable the subject of poems has been since ancient times. Most poets write about love, death and how we can have meaningful lives in the short time that we are given, which seems to be present in poetry across many different cultures and languages. In class we study poems by Sappho, Shakespeare and contemporary and 20th-century poets and how their attitudes are shifting slightly about what gender is, what marriage is and how openly love can be expressed. Students will write their poems and contribute to that very long, ancient conversation about the relationship between art and love.

TSD: How has being a recipient of the Wallace Stegner Fellowship influenced your literary path?

RH: The Stegner Fellowship was probably one of the best things that ever happened to me as a writer. I was at the point where I had finished my writing education in a formal sense. I was not sure exactly where to turn, and the Stegner Fellowship came just at the right time. I received a call from Eavan Boland, who became my mentor and one of the most profound and significant teachers in my life. She was really hard on me and made me think more deeply about my poems, about my craft and about what it meant to be a poet.

Michael Shewmaker

Shewmaker, known for his collection of poems “Penumbra,” offers an innovative reimagining of the religious text “The Book of Job” in his new collection, “Leviathan.” Michael Shewmaker is the recipient of fellowships from the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference and Stanford University, where he now teaches several undergraduate poetry classes.

TSD: I really enjoyed the musicality of your poem “Pastor,” namely the alliteration of sounds: “The pale horse is snoring / in its stall. Strike a match and light the straw.” Your poems are pleasant not only to the heart but also to the ear; how do you achieve this effect?

Michael Shewmaker [MS]: Sometimes I don’t even know. It is just a matter of reading my poems obsessively over and over again to myself until I love how they sound. It’s also a matter of having schooled on the meter in prosody, in rhyme — in the different ways we can make a sound in a language. I rarely think about the sound in the initial composition, but do it obsessively in revision.

I think the greatest artist understands the limitations and benefits of their mediums. One great benefit writers have is that you can click the “save” button and then open another document. There is never a risk of damaging what you’ve already written, so you can always play and see if you can come up with something better. But when you think about other artists, that’s not always the case. Visual painters can do something to cover up a mistake, but eventually, the paint gets too thick.

TSD: What do you think the voice of your new poem “Leviathan” is like?

MS: I hope it’s more personal compared to “Penumbra”, even though it’s spoken through a character. Also, since it is a much longer work, I hope that you live with the characters longer. It’s like the difference between reading a really good poem and reading a really good novel; the novel asks you to live with it a lot longer than the other. So I think about my second book in that way: that sort of echo in livability with the characters.

TSD: How has the Stanford community shaped your work?

MS: The Stegner Fellowship was a huge thing in my life because, for any artist, the greatest thing you can have is the time to focus on your craft. I was surrounded by wonderful people and writers whom I really admire. All these things affected my work: I made friendships that have lasted until today, and some of the very first readers of my poems are from the fellowship. I can’t say enough to stress how important it was for me at that time in my life and since then.

When I think about the Stanford community, my colleagues and students being extremely affirming and hopeful and coming from so many different backgrounds, I think it’s like a miraculous constellation that is not ever likely to happen again.

Brittany Perham

Perham has written the poetry collection “The Curiosities” and the collaborative chapbook “The Night Could Go in Either Direction.” Her latest work, “Double Portrait,” earned the 2016 Barnard Women Poets Prize. Perham teaches world poetry and composition at Stanford, and she led a Poet’s House lecture series last year.

TSD: I really love the three-time repetition of the phrase “Today is very small” in your poem “DP.agp.11.” What figurative meaning does it have?

Brittany Perham [BP]: That poem has the form of a pantoum, which has very strict rules of repetition. This poem comes from the book “Double Portrait,” and every poem in the book is a kind of double portrait. It’s interesting to investigate relationships between the self: a fictional “myself” or someone else.

In “DP.agp.11,” the speaker is dealing with what it means to have a relationship that is occupying all of one’s attention but is not active in the present. This poem is full of longing that can be very isolating and difficult to negotiate in the world.

TSD: During the fall quarter you have been a lecturer in the Poet’s House. How would you describe this experience? Why did you decide to build the curriculum around memory?

BP: Poet’s House is an amazing program that anyone in the Stanford community can join. It’s something we do every quarter, and different lecturers take turns leading the workshops. You can meet a lot of people in the community that you wouldn’t otherwise.

I decided to do this series about memory because it often plays a big part in the moment of inspiration. Even if we are not going to write a poem that is fully non-fiction, something in our lived experience might be that drive to write.

TSD: How has teaching at Stanford enriched your life? How do you think a lecturer can learn from their student?

BP: There is no better thing about teaching than learning and being in a room with your students. Writing can feel very solitary: you’re doing your work alone, sitting at the computer and everything is based on you and a page. The great thing about being a teacher is that you have this other part of your life where you engage with other people, their own sets of concerns and their brilliance.

I believe what has been the most profound to me about teaching at Stanford is getting to know my students very deeply in a 10-week quarter. [Students take] a lot of risk in the writing workshops — writing about family and bringing up the things they are mad about. As a result, I get to know them very well, and they get to know each other too. At workshops, we all work together; I often do the same exercises along with my students. It feels like magic!