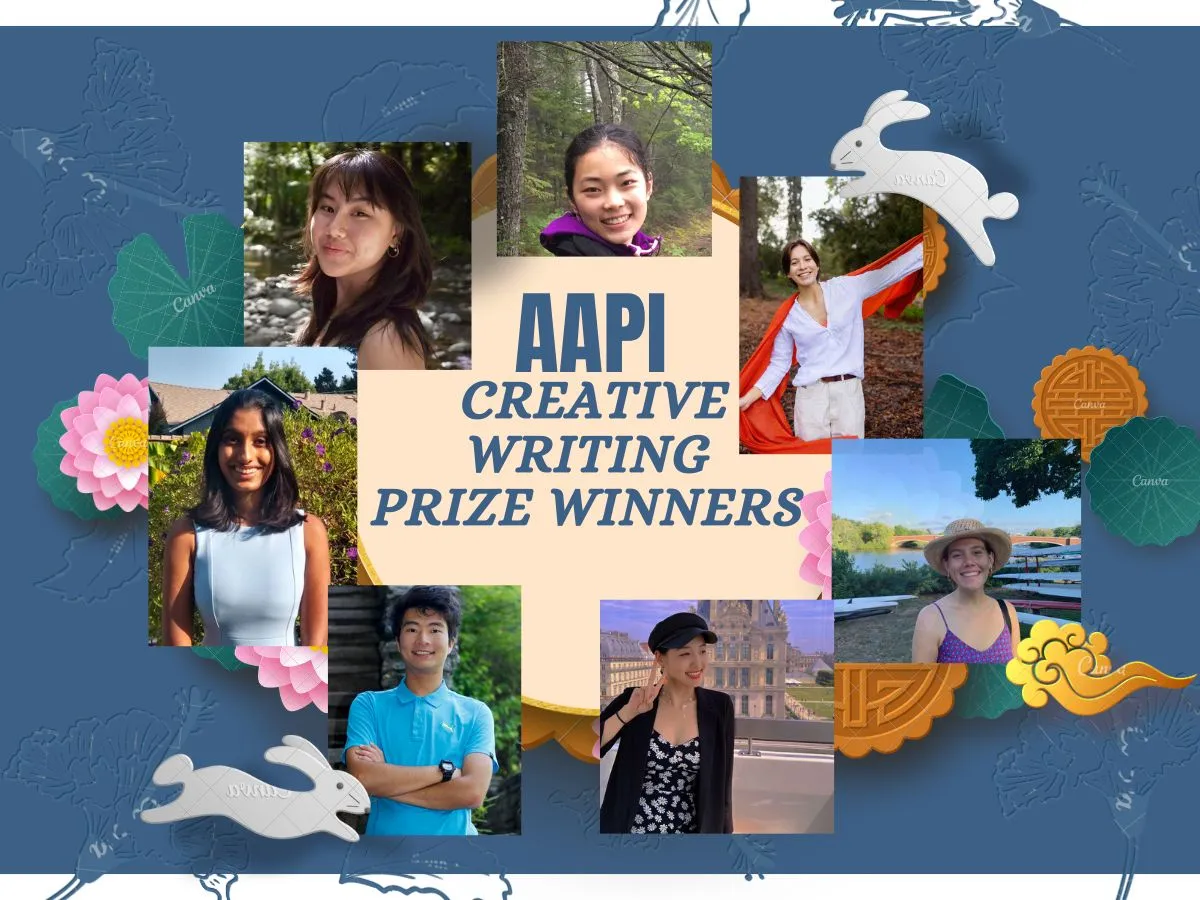

Every year, the Creative Writing Program hosts a writing competition, calling on students to enter their work in a wide number of prize categories. With submissions due in late April, the winners were announced last Friday; notably, several prize recipients identified as Asian American/Pacific Islander (AAPI). In honor of May being AAPI Heritage Month, The Daily sat down with a number of these students to discuss their work.

Nandita Naik ’23 M.S. ’24 – Bocock/Guerard Fiction, Second Prize – “When I Grow Up, I Want to Be a Fossil”

Set in a near-future dystopian world’s prehistoric-themed amusement park, “When I Grow Up, I Want to Be a Fossil” follows a young woman’s search for a sense of agency amid the chaos caused by uncontrolled wildfires. The piece came about during Naik’s Levinthal Tutorial with Stegner Fellow mentor Georgina Beaty, when Naik said she set out to write climate fiction.

The prize-winning fiction story is marked by the depth with which Naik describes prehistoric events and creatures. This is drawn from her broader “interest in the stories of the past,” which she attributes as being “learned from [her] heritage.” During childhood visits to her grandparents in India, Naik enjoyed reading historical and mythological comic books.

“Mythology and history were presented with equal authority, which was really interesting,” she said. “I didn’t grow up [in India] so learning about the stories that took place and approaching everything with a sense of humbleness really affects the way that I write.”

Yu chen (Rellie) Liu ’24 – Creative Nonfiction, Second Prize – “Last Breaths”

In her piece “Last Breaths,” Liu offers readers a peek into a summer spent in her hometown of Dalian, China, during the pandemic. She utilizes a braided narrative to draw connections between her experience learning how to freedive and her time volunteering in a morgue. As Liu learned how to appropriately hold her breath underwater, she also observed how funeral practices brought mourners peace after loved ones had taken their last breaths.

During this time, Liu was grappling with her grandparents’ passing. She described herself as “on the run from [her] hometown for a very long time,” but said she found solace in diving.

“I was living in all sorts of different places — just not in my hometown — so the diving experience was really calming in a certain sense,” Liu said. “It made me realize that I wanted to face death instead of run away from it.”

Through her involvement with the morgue and attending her family members’ funerals, Liu learned about the Chinese traditions around mourning, from the feng shui of a grave’s location to the order in which relatives burn funerary incense.

While these new kernels of cultural knowledge informed her summer spent in China, Liu described her creative nonfiction piece as focused upon her “psychological growth.” Coming to terms with her grandparents’ deaths taught her that “death is not the opposite of life, but a part of it” — a Haruki Murakami quote which prefaces Liu’s self-transformative piece.

Max Du ’24 – Creative Nonfiction, Third Prize – “All the Stars in the Air”

“All the Stars in the Air” chronicles Du’s experience growing up with family pressure to engage in various athletic activities. Having immigrated to New York from mainland China, Du’s mother sought to help him assimilate into a vision of the “American Male” who excels in sports. As a means to this end, she offered her son incentives in the form of illegal fireworks.

When approaching the topic, Du aspired to write about his mother in a compassionate manner and understand the reason behind her attempts to help Du fit in with his American peers in a village that was “95% white,” according to Du.

“I use the term ‘broad brushstrokes’ [as a metaphor for] the larger perspectives of this white identity she saw onto me,” Du said about his mother. “She did really come from a place of love and compassion as a lot of moms do. She just saw a prototype of the world and she tried to get me to adapt to it.”

While Du’s mother did encourage his assimilation to her vision of an American identity, she still tried to maintain connections with the family’s Chinese cultural roots. For instance, Du’s parents would go to an Asian market for groceries rather than the local American market.

“I think that this is a common narrative of ‘Where does my culture stay and where do I have to leave for this newer culture?’” Du said. “But I think there are ways of making the culture you’re born into and a new one collaborate together.”

Huali Kim-O’Sullivan ’23 – Planet Earth Arts Creative Writing, First Prize – “NALU”

“Nalu,” roughly meaning “wave” in Hawaiian, depicts the struggles of a diasporic Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiian) girl who returns to Hawai‘i just to encounter a climate disaster that damages her home and community. The story draws heavily upon Kim-O’Sullivan’s personal experience as a diasporic Pacific Islander seeing the impact of climate change on her family.

From her personal understanding, many members of the Pacific Islander diaspora hope to reconnect with their homelands in the Pacific because of the deep, emotional ties many have with the land. It is “where the bones of our people are and we are made out of the bones that are made out of that land,” according to Kim-O’Sullivan.

Seeing how meaningful the physical space is to the hearts of Pacific Islanders — whether they live on their homeland or not — the threat of climate change is quite frightening. Even if the islands aren’t going underwater, many residents of the Pacific have to grapple with a future where weather and storms may become so violent that their homes are no longer safe.

“That scares me as someone who is diasporic and someone who doesn’t want to be separated from my culture or my people or my community, because even though growing up in the diaspora is fantastic, there can be a lot of loneliness and isolation — especially when you’re not able to find community in certain spaces,” Kim-O’Sullivan said.

Isabella Nguyen Tilley ’23 – Planet Earth Arts Creative Writing, Third Prize – “There Will Be Fire”

Drawing from Tilley’s Vietnamese-American heritage, “There Will Be Fire” is a speculative fiction piece centered around an intergenerational Vietnamese American family that is being uprooted from Clovis, CA in the 2060s due to the impending danger of a wildfire.

Being exiled from a place that has been home to generations of one’s family is unfortunately a familiar feeling for a number of Vietnamese-American refugees — as expressed by a body of Vietnamese American literature — but is not exclusive to a single cultural identity, according to Tilley.

“There’s a nostalgia and longing [in the story], which is relatable to a lot of other diasporic communities,” Tilley said.

Many of the story’s character dynamics and identities came to Tilley “intuitively.” As Tilley was most familiar with the feeling of having a Vietnamese mother, the family of Vietnamese Americans in their story featured only women.

Lora Supandi ’23 M.A. ’23 – Urmy/Hardy Poetry, First Prize – “Bandung Funeral”

In their poem “Bandung Funeral,” Supandi centers on residents of Bandung, Indonesia during a period of time preceding an infant’s funeral.

Supandi is interested in how historical events shape mortality and what hope looks like during times of imperialism and genocide. A question their work considers is, “How are we pierced by cultural memory – the ephemeral, its decay, morphed by grief, history and generational wounds?”

Supandi seeks to understand the ways by which their Indonesian American community can be freed from oppression within the U.S. They utilize bilingual poetry as a vehicle to connect with their Hakka Indonesian heritage and history. This writing medium is also a way to explore core themes like love, heartache and devotion — which “pull us back to one another” — in the face of such tragedy, according to Supandi.

“In a society where punishments often enact a sentencing, poetry can be a space to seek possibilities outside of these harmful systems,” Supandi wrote. “In my writing, I want to break away from closure.”

Kate Li ’25 – Urmy/Hardy Poetry, Second Prize – “As Relic, As Remnant”

The trend of residential displacement in hometown Chicago, Ill. inspired Li to write “As Relic, As Remnant.” The poet has come to see the process of gentrification as something “modern society is willing to do a lot of in order to prove itself as ‘contemporary’ or ‘striving for change.’”

Displacing traditional values or customs in the name of growth is an idea expressed in Li’s work — namely, through the themes of cultural artifacts, bodily imagery and historical processes. Communities that are displaced in urbanization and modernization changes often don’t get their voices heard. Thus, Li sees poetry as “a practice that reframes these acts not from the side of people with the most agency, but instead from the side of people who become by-products of these processes.”

Having such a marginalizing experience is a pattern that Li has noticed among the Asian American community.

“Our narratives are frequently rewritten by whatever society and social practices we’re inducted into,” Li said. “Coming from this Asian background, it’s become really important to reframe your history as one that belongs to you and not the people whose frameworks you operate within. This is a practice that I build upon and is especially critical for the formation of this poem.”

Malia Maxwell ’23 – Urmy/Hardy Poetry, Third Prize – “Pō”

“Pō,” or “Night,” (roughly translated from Hawaiian) is a dictionary poem, which delves into the poetic and associative definitions of a particular word, beyond its conventional meaning. As Maxwell began learning the Hawaiian language, she was inspired to explore the meaning of certain Hawaiian words.

According to Maxwell, Hawaiian can be a metaphorical language since the words have many different meanings. As such, Hawaiian words don’t always map onto English terms very well. Some are used as a noun, verb and adjective. In “Pō,” Maxwell explores Hawaiian word use as an aspect of the culture.

“I moved through noun meanings of the word, verb meanings of the word and adjective meanings of the word using these different sentences,” Maxwell said. “They don’t necessarily all connect with one another directly, but I think overall, they kind of build up to a certain something.”

Some words in Hawaiian have more meaning and emotion behind them than can be conveyed by their direct English translation. For instance, “aloha ‘āina” and “mālama ‘āina” are used to speak of one’s “love for the land,” and are associated with the “love, reverence and [protectiveness]” that Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) may feel toward their homeland. Maxwell aspired to make readers feel this profound sentiment.

Speaking about the land, she said she wanted to capture “its power as something that demands respect from the reader.”

A previous version of this article included incorrect spellings of several Hawaiian words. The Daily regrets these errors.