One hundred new shelves containing free Narcan and fentanyl test strips will be installed in dorms across campus starting this week.

Students began advocating for more opioid harm reduction resources on campus following the death of a student due to an accidental fentanyl overdose four years ago. Now, Narcan — the nasal spray that reverses an opioid overdose — and fentanyl test strips are widely available on campus, including in student residences.

Just months after the student’s overdose, Max Moss ’21 and Nicole Ticea ’21, now a third-year Ph.D. in applied physics, took HUMBIO 163: “The Opioid Epidemic: Using Neuroscience to Inform Policy and Law” in spring 2020. The class — which covered both the neuroscience behind opioid use and the policy initiatives that could address the epidemic — inspired them to propose a Narcan program on campus.

Vilina Mehta ’22 M.S. ’23 M.D. ’28 did not know what fentanyl was, let alone its nationwide impact, prior to taking a different health policy class where she created a policy intervention to bring harm reduction strategies to college campuses. After learning about CO-OP from a professor, she partnered with Moss and Ticea to start the Campus Opioid Overdose Prevention Project (CO-OP).

The trio started CO-OP with two goals: training the campus community to recognize and respond to overdoses and raising awareness about the opioid epidemic.

Mehta said their work was initially met with resistance from the University, which at the time, took an abstinence approach to regulating opioid use on campus. However, following persistent advocacy and with faculty support, CO-OP began working with the Office of Substance Use Programs Education & Resources (SUPER) in September 2021.

“Our work really shifted the narrative at Stanford from being an abstinence-focused approach to being like a harm-reduction approach,” Mehta said. “The goal of harm reduction is to save lives and ensure that something like what happened in winter 2020 doesn’t happen again.”

The University did not respond to a request for comment on its previous harm reduction policy.

Mehta began teaching student health peer educators, called PEERs, how to lead their own Narcan trainings last year. Since February 2023, PEERs have held hour-long, biweekly Narcan trainings at the Well House, a substance-free dorm.

Natalie Lynch, the assistant dean of students and director of education and outreach for SUPER, said trainings instruct participants on how to detect an overdose and how to use Narcan and fentanyl test strips. The trainings also cover the history of the opioid epidemic and the resources available to students on campus.

“We spend time working through different scenarios where folks might encounter an opioid overdose and really walk through how to address that step by step, so that folks walk away with more of that confidence around managing that situation and knowing what to do,” Lynch said.

According to SUPER, over 1,400 Stanford affiliates have participated in Narcan trainings since 2020. Students, staff and faculty can drop by the Well House for trainings, and any affiliate can request a training for organizations they are part of.

“We know from past surveys that 98% of students walk away feeling like they are confident in identifying an opioid overdose and 99% of students said, ‘Yep, I feel prepared to administer Narcan in an opioid overdose,’” Lynch said. Participants are given Narcan to carry with them around campus after the trainings.

Overdose detection and using Narcan and fentanyl test strips have also become a mandatory part of resident assistant (RA) training as of the 2022-23 school year. Mehta has led RA trainings for the past two years since SUPER hired her as a harm reduction specialist.

Ralph Castro, associate dean of students and director of SUPER, said the goal is “always to increase access to Narcan across campus.”

“It’s a safe medication that saves lives,” Castro said. “And so we intend to continue to expand access in every way we can.” Narcan and the test strip kits can also be found at SUPER’s office in Rogers House.

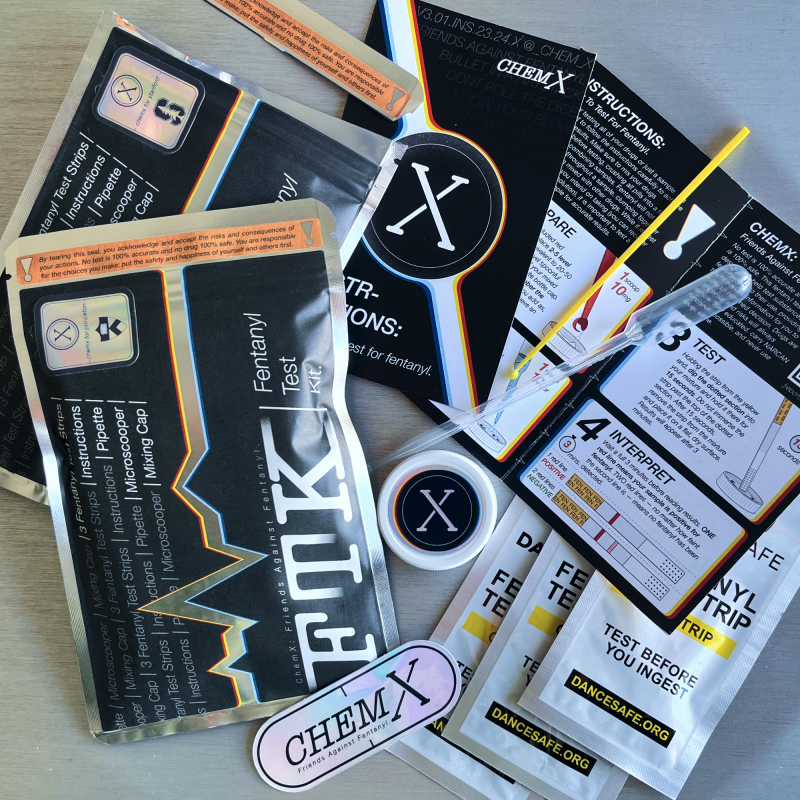

Fentanyl test strips, which can provide results in under five minutes, are another key part of the trainings. They are available on campus as part of the Chem-X initiative.

Chem-X founder Alec Manko ’23 noticed the same issues as Mehta, Moss and Tecia regarding opioids on college campuses. Manko said that the fact that fentanyl overdose is the leading cause of death for young Americans was reason enough to take action and provide resources to help students understand opioid use and access to harm reduction strategies on campus.

Manko said he approached “this as a design problem.”

“With such a stake in the matter, as this is something that affects me, my community, my classmates [and] my students, I believe that everyone should care about [this] and everyone should be a champion for drug safety and not just look the other way,” Manko said.

Last year, Manko began making the testing kits with three fentanyl test strips, instructions, a pipette, a microscooper and a mixing cap. He put them in a few dorms to test the product, and by spring, SUPER and Chem-X collaborated and put the kits in over 20 dorms, focusing on Row houses.

Manko said the goal of Chem-X is not to “preach abstinence” — instead, it takes a proactive approach to drug safety.

“The slogan is ‘friends against fentanyl.’ It’s friends helping friends stay alive and safe,” Manko said. “How an issue like this is averted and how we stop losing so many lives to accidental overdose is by peers standing up and engaging and helping other peers.”

The newly installed Chem-X shelves include free fentanyl test strip kits, Narcan and educational and reporting resources that can be accessed through a QR code. Students can also use the QR code to request for the station refills.

Participants of the Narcan trainings learn that fentanyl test strips are not fail-safe through a “chocolate chip cookie paradigm.”

“Let’s say you cut a pill in half, and you test it, and it’s negative, which means there’s no fentanyl,” Mehta said. “That drug still may not necessarily be safe because like the other half of the pill might have fentanyl in it.”

Castro said it is important for students to understand how widespread fentanyl is.

“It’s a very serious epidemic, and it is very serious here in Santa Clara County. We’re one of the epicenters of the opiate epidemic,” Castro said. “One pill can kill. You have to expect fentanyl in any type of illicit drug that you get on the illicit market.”

Biweekly Narcan training sessions resumed this year on Monday, Oct. 16 at 7 p.m. at the Well House.

Students struggling with substance abuse can seek help on campus through the Office of Substance Use Programs Education & Resources (SUPER).

A previous version of this article misstated the number of new shelves and the name of one of the CO-OP founders. This article has also been corrected to more accurately characterize the founding of CO-OP based on updated information from the founders. The Daily regrets this error.