In “Talk Horror to Me,” columnist Emma Kexin Wang ’24 reviews horror, psycho thrillers and all things scary released in the past few years. Spoilers ahead, read with caution.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.

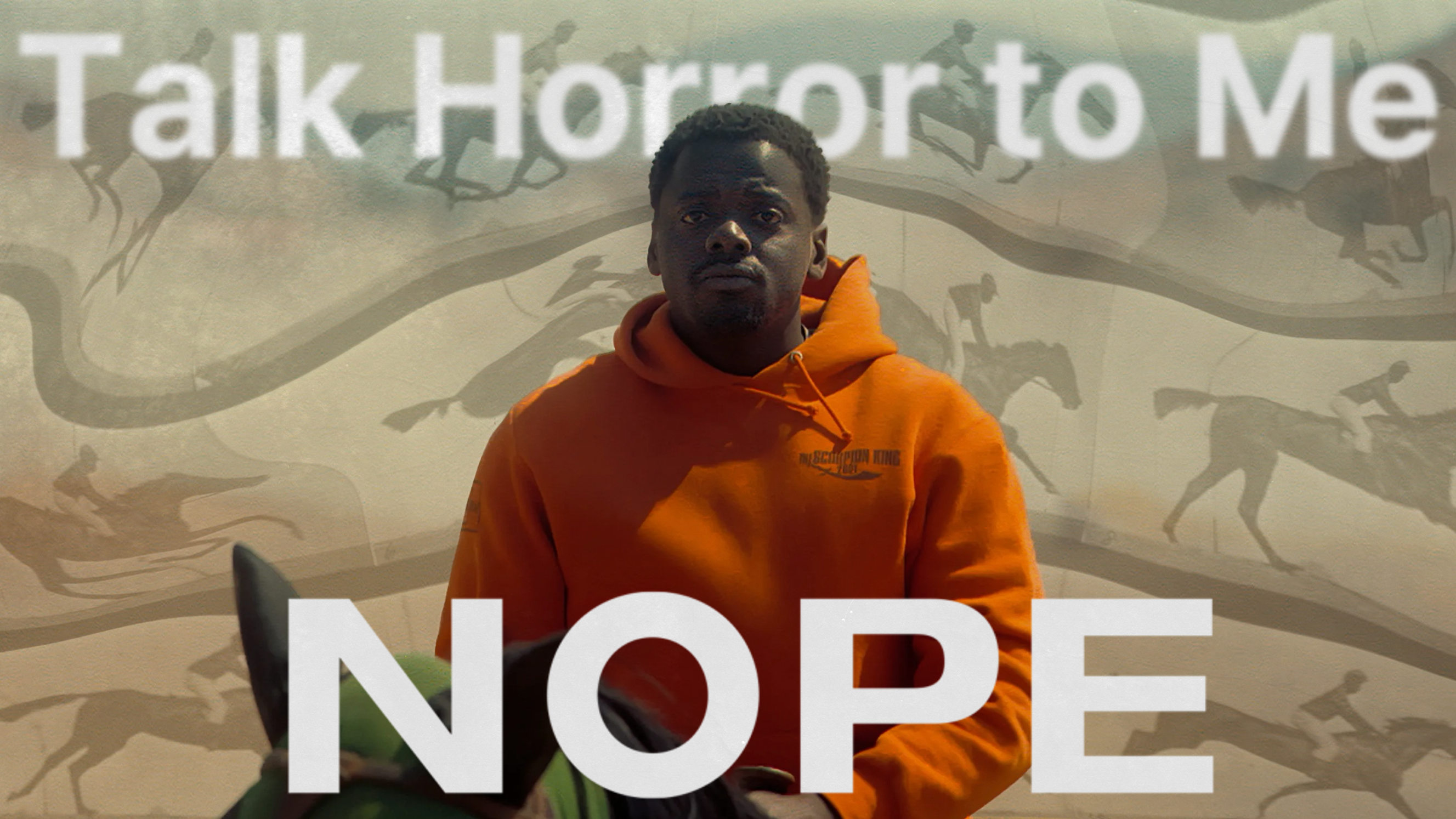

After the success of “Get Out” and “Us,” Jordan Peele returned to the horror scene with “Nope” in 2022. The film offers fun twists on cowboys and aliens in a less-scary but self-reflective story about documenting traumatic events — and the very film industry Peele works in.

Featuring a relatively simple plot, “Nope” feels distinctive from Peele’s first two films, known for plot twists at the end. The film follows Otis Jr. (or OJ, played by Daniel Kaluuya) and his sister Emerald (or Em, played by Keke Palmer) — both members of a family of horse wranglers — as they try to photograph a UFO that had killed their father. Two other characters, a tech bro and a famous cinematographer, aid them in their quest in search of Oprah-worthy fame.

The film opens with an extremely disturbing scene. At the back of a live stage facing an empty audience, an unconscious body lies on the floor. We hear heavy breathing and see a handheld camera slightly moving under the table, suggesting we are hiding with someone. A bloody chimpanzee appears on screen after a series of slow, heavy thuds. He pushes the body’s unmoving leg, sits down and hurls the body away.

Soon, we discover that the person hiding is child actor Jupe (Steven Yuen), who was to appear in a comedy on the stage, but his co-star, a chimpanzee named Gordy, went haywire and killed all the actors except him. Jupe then grows up to become the manager of a Western themed park and buys horses from the film’s protagonists, OJ and Em.

At its core, “Nope” highlights two problems that arise when confronting personal trauma: marketing trauma as a commercial experience and a perverse voyeuristic desire to look at depictions of traumatic events, a sentiment coined “trauma porn.”

Jupe is unable to look his trauma in the eye. He portrays the day of the killings indirectly through a reenactment of a Saturday Night Live skit instead of confronting his own experience. A group of show fanatics request to pay money to stay on this set overnight. Jupe obliges, capitalizing off of his childhood trauma by making it a consumable experience for others.

Interestingly, Jupe turns trauma into a spectacle, with him as the director. He produces a show using a horse as bait, intending for the UFO to suck the horse inside the vessel. Instead, everyone in the audience, including Jupe himself, are engulfed, leaving the horse ironically unscathed.

After OJ witnesses the UFO attack, he realizes that the UFO is a predatory being that only attacks when directly looked at. To avoid being sucked up, the four-person photography crew only had to avoid the animal’s “gaze.”

Holst, the famous cinematographer helping OJ and Em photograph the UFO, becomes obsessed with the idea of the “perfect shot,” and aims his camera directly at the UFO’s large, black-hole of a mouth. He gets sucked up into its stomach.

Beyond visualizing what it means to observe trauma, “Nope” also reckons with the film industry’s historical erasure of Black people. After the title card, an unsettling sequence — that we later learn is inside the UFO — rolls into a black-and-white scene of a Black man riding a horse.

For film fanatics, the sequence is familiar. It is a clip from the first ever moving picture, as Em later explains. Commissioned by Leland Stanford, photographer Eadweard Muybridge captured a horse’s running motion in a photo series.

Though many remember Muybridge, there is no record of the Black person pictured in the film. From the very inception of film, Black people and the roles they played seem to be erased from our cultural memory. The protagonists, Em and OJ, are fictionalized great-great-great grandchildren of the “actor” in Muybridge’s photographs.

In the end, when Em successfully snaps a picture of the UFO, she looks over at the entrance of the Western theme park. There, in the mist, is OJ atop a horse — he has survived the alien attack. The frame of the entrance and the blurriness of the scene recalls the Muybridge clip.

Through fiction and film, Peele has attempted to fill a historical gap. The ending, with our protagonists alive and their goals achieved, offers a frame for Black joy and possibility.

This article has been corrected to reflect that Gordy is a chimpanzee, not a monkey. The Daily regrets this error.