In “Cardinal Canvas,” Adam Golomb spotlights art on and around the University, exploring and reviewing artwork that students may otherwise miss.

Editor’s Note: This article is a review and contains subjective opinions, thoughts and critiques.

How much of a person’s story can be told by their eyes? Their smile? In “The Faces of Ruth Asawa,” the titular artist explores the deep intimacy of gazing into another person’s soul and the nuances that emerge from a singular, captured expression.

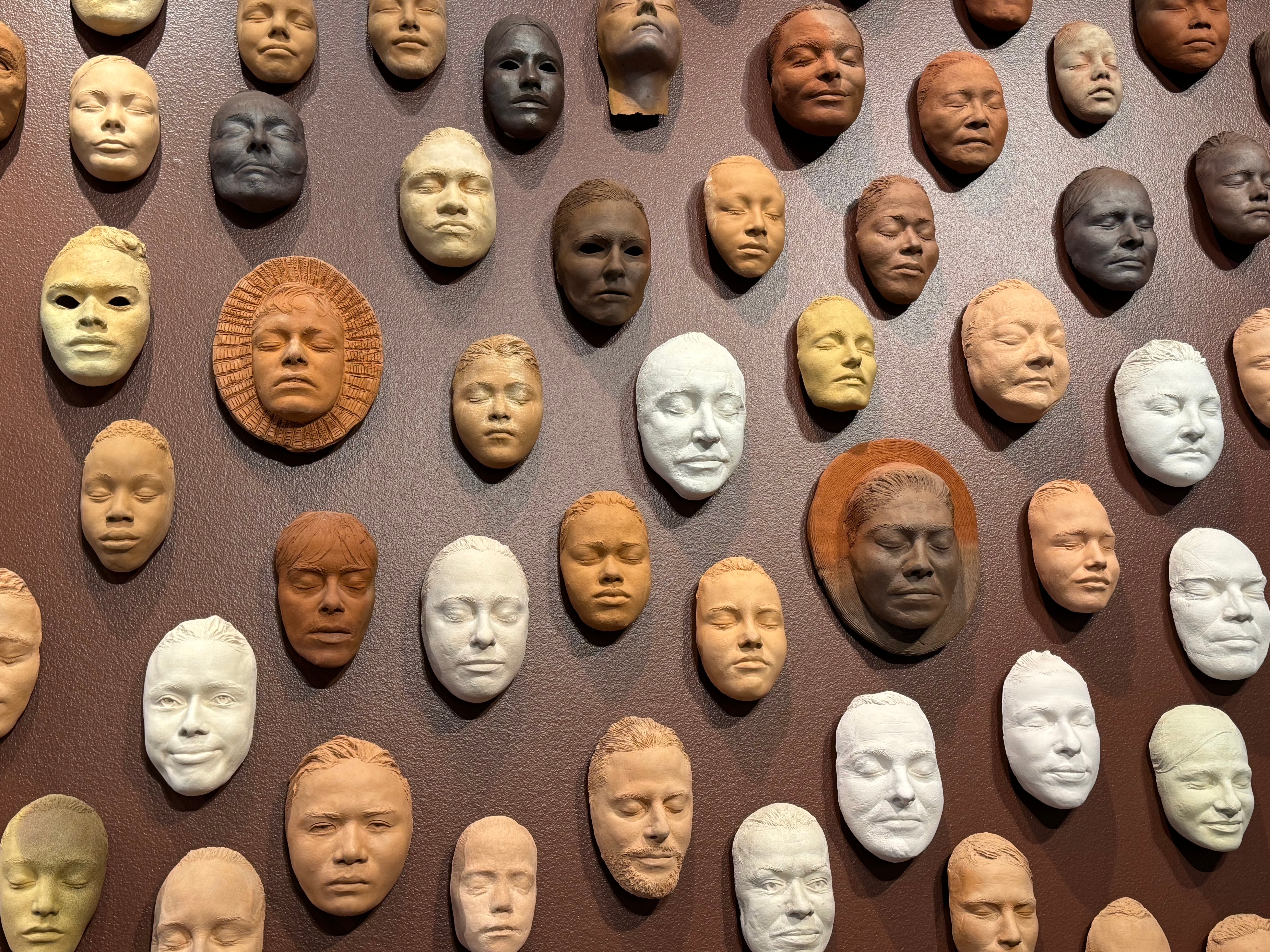

“Faces” comprises of 233 ceramic face masks, each a hand-molded clay cast of Asawa’s friends, family and community, hung up on a brown wall. Alone, each one represents a fragment of her heart, but together the piece creates an illustrious web of love and dedication — to and from the people in Asawa’s life.

I got lost in the faces. Their individual expressions are immediately mesmerizing. Each cast is unique, telling a diversity of stories. A child’s face with cherubic cheeks and eyes close to the nose will be placed next to a wrinkled face, smile lines laden with wisdom. With just a mask, Asawa encourages the viewer to engage and immerse themselves in the world of that face.

Before coming to the Cantor in 2022, “Faces” lived on the exterior entryway of Asawa’s personal home. Asawa creates an army of her loved ones, the faces that protect her, proudly displayed outside her home as a shield. The first mask created in the project at the very top is Asawa’s herself, the root of her own support network.

Considering how each mask is cast from a loved one, “Faces” represents the impact the people in Asawa’s life had on her. But she also had a massive influence on her community as a passionate advocate for equal access to the arts. The pamphlet about the exhibit at the Cantor details how, after initially being barred from attending arts university due to racial discrimination, Asawa championed a democratic approach to art. She was a pivotal force in establishing the public Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts, which is now named after her.

Most of the masks in “Faces” have their eyes closed. From a logistical standpoint, this makes sense: When someone’s face is being casted in plaster, they naturally close their eyes.

So when a face was captured with open eyes, I fixated on it. One in particular, right in the middle of the piece, gazes at the viewer with a tired expression. I stared back, as if in a visual conversation. This is the power of Asawa’s exhibit: It prompts the viewer into a pseudo-intimate relationship with a face they don’t recognize.

One mask, towards the top, stands out as the only one with a neck. The face points up in a grimace. The expression was likely in anticipation of the plaster, but it reminded me of both the humanity and temporality of each mask. Asawa preserves a momentary snapshot of each person and their narrative. Each expression is ephemeral, yet sustained and fixed in clay, a lonely moment frozen in time.

I love viewing “The Faces of Ruth Asawa” from both the perspective of Asawa and that of an outsider. To Asawa, the masks are portraits of her family and closest loved ones, yet to anyone else, they are narratives to explore and project conversation onto. This dichotomy reminds me of the beauty of art that is made for oneself; to witness Asawa’s personal reminder of her values is profound.

Cantor’s new exhibit “Day Jobs” opened this Wednesday. “Faces” is right across from the new exhibit — if you visit, I implore you to take a moment and look into Asawa’s life.