Vince Pane Ph.D. ’23 was returning to his apartment at Blackwelder in November 2021 when he found himself stuck in an elevator between floors. Pane initially tried to call for rescue using the alarm and emergency call buttons, but found that they did not work, and his phone had no signal.

Pane, an American Ninja Warrior semifinalist, first tried to pry open the door with a knife from the dining hall, to no avail. Then, he climbed onto the elevator railings and proceeded to dislodge a ceiling panel with a series of kicks. As he recorded on his phone, he hoisted himself out of the shaft and jumped onto the next floor.

Later that day, Pane said he found the elevator blocked off with yellow tape. By the next day, it was up and running again, Pane said. As he heard no work on the elevator during the night, he believed that nothing was ever truly fixed.

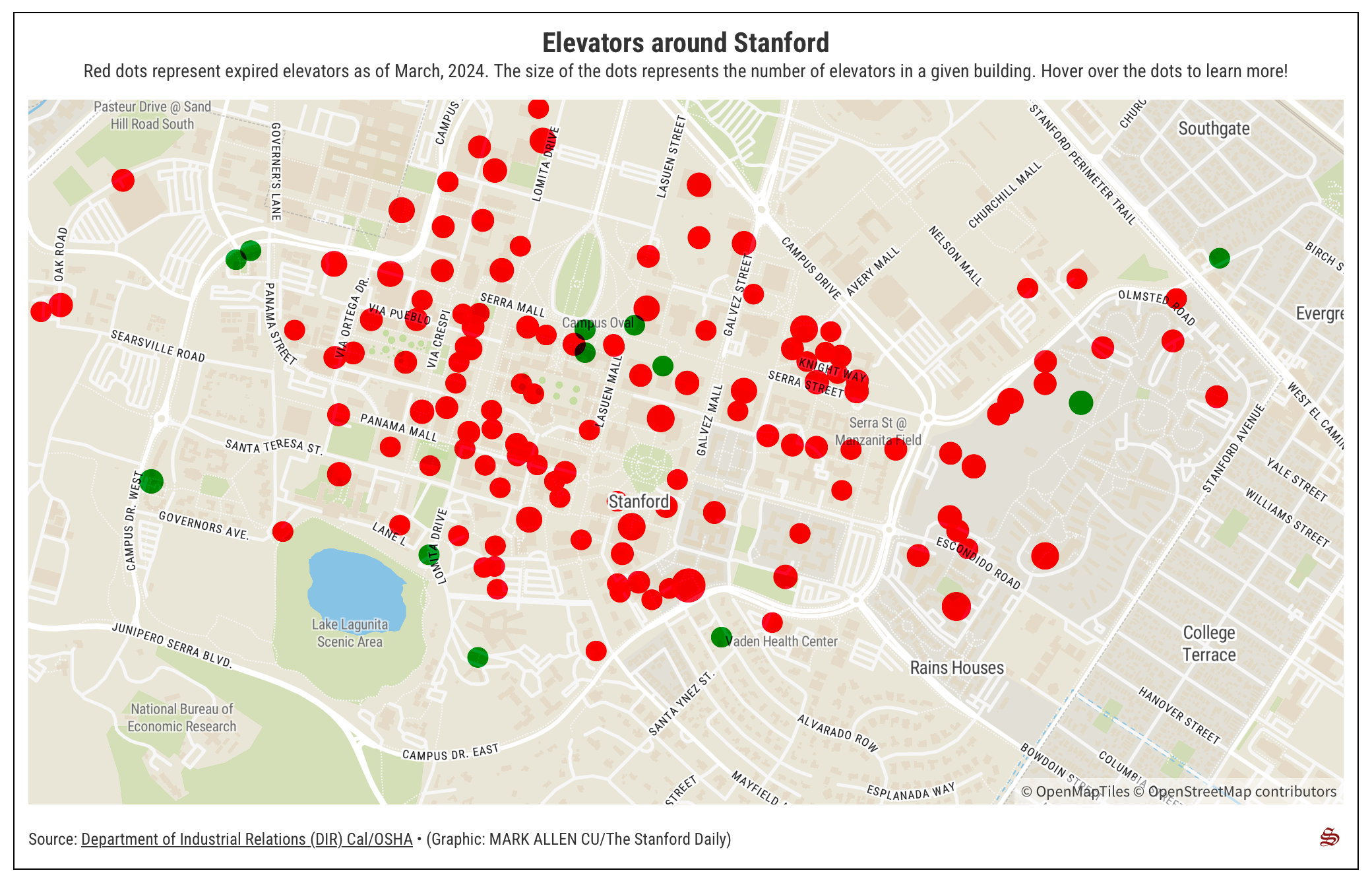

According to Pane, the Blackwelder elevator’s permit was expired at the time. Though it has since been inspected, its permit expired once again on Aug. 12, 2023 — making it just one of the 260 elevators on campus, 94% of a total of 274, with expired permits, according to documents obtained by The Daily through a public records request. On average, each expired elevator is over 160 days overdue.

On their way to an ice cream study break on May 30, 2022, Carlene Sanchez ’24 and Katelin Rose Zhou ’24 free-fell two stories in an EVGR-A elevator and landed between the first and second floors. Zhou, Sanchez recounted, began catastrophizing.

“She was like, ‘What if someone calls it on the 10th floor, and then we go to the 10th floor, and then it drops?’” Sanchez said.

According to Sanchez, they were rescued by the Palo Alto Fire Department 20 minutes after repeatedly pressing the call button.

The Daily spoke to several students who shared similarly harrowing experiences with faulty elevators across campus. The doors of the elevator in Ng often open before the elevator has finished descending. An elevator in the Spilker Engineering & Applied Sciences Building has stuck buttons. An elevator in the McClatchy Building has its open and close buttons switched.

All of these elevators have expired permits.

An elevator mechanic, who requested anonymity out of fear of retaliation, told The Daily that elevators with expired permits are often unsafe to use.

“[Parents] have a reasonable expectation that their children would be safe [here], right?” they said.

Each year, dozens of elevator rescue requests made to the Palo Alto Fire Department originate from the Stanford campus, including 41 in 2021 and at least 38 in 2022, Palo Alto Online reported.

Legal experts told The Daily that Stanford would bear liability in a potential lawsuit on the basis of expired permits or injuries resulting from an elevator malfunction. The University subcontracts its elevator maintenance to KONE, an elevator engineering company based in Finland.

“The University maintains a full-service elevator maintenance contract with an outside service provider [KONE] that provides planned, reoccurring preventive maintenance as well as reactive coverage requiring one hour response time, 24/7,” wrote University spokesperson Luisa Rapport in a statement to The Daily.

Rapport wrote that KONE provides routine maintenance, despite state-wide inspection backlogs, and is expected to respond to elevator reports and outages within an hour.

KONE did not respond to The Daily’s request for comment.

The California Code of Regulations mandates that “No elevator shall be operated without a valid, current permit issued.”

Palo Alto Online reported in December 2022 that there was a backlog in elevator inspections of more than two years in the San Jose district, which includes Stanford’s campus. Just nine inspectors are responsible for the district. The California Division of Occupational Safety and Health (Cal/OSHA) acknowledged the need for more elevator inspectors and told Online that hiring was “a top priority.”

“The safety of our campus elevators is a top priority,” Rapport wrote. “Stanford remains in compliance with inspections and permit requests, but does not rely on the state inspection to ensure the safety and operation of our elevators.”

After The Daily’s inquiry, signs began appearing on elevators across campus informing riders that the elevator was “routinely inspected by the State of California.” Records showed that many of the elevators bearing these notices had expired permits.

Accessibility issues arising from faulty elevator

Members of the disability community told The Daily that broken elevators significantly impair their daily lives. Adri Kornfein ’25 recalled having a “difficult” experience when she lived in Meier during her sophomore year. She uses crutches and lived on the third floor, relying on the building’s single elevator to travel to and from her room. That elevator, Kornfein said, was broken for half of the two quarters she lived in Meier.

According to Residential & Dining Enterprises’s website, all floors of Meier “are accessible.” Nevertheless, Kornfein said she left the dorm last spring without the elevator ever having been permanently fixed. That elevator’s permit is currently expired.

Kornfein said relying on Meier’s defective elevator was stressful. “Sometimes I would just stay in my room instead of going [downstairs], because it was hard to get up and down [the stairs] so many times,” she said.

Stuart Seaborn, the managing litigation director of the nonprofit Disability Rights Advocates, said his greatest concern with unsafe elevators was their impact on members of the disability community.

“Broken or non-maintained elevators pose a systemic problem to members of the disability community, and we have litigated that issue on multiple fronts,” Seaborn said. “When [elevators are] not maintained, they present a significant barrier.”

University spokesperson Mara Vandlik wrote, “A review of our records does not reveal any long-term outages for the elevator in Meier Hall last year.” The only extended period of outage happened in late October 2023 for 10 days, when parts had to be ordered before repairs could occur, she wrote.

Lloyd May, a fourth-year music Ph.D. student and former ASSU director of disability advocacy, said that Stanford’s inaction on elevator safety is one of many examples he sees of the University’s “systemic silo-ing” when it comes to addressing the needs of the disability community. Support for the disability community is handled by many different departments and offices that have little communication with one another, resulting in many inefficiencies, he said.

Similarly, Cat Sanchez ’19 M.A. ’21, former co-chair of the Stanford Disability Initiative, said it was “frustrating” for students with disabilities, who often get “very, very slow change or very slow response” when they raise concerns. She criticized the University for leaving students “in the position of having to ask for help” when University facilities like elevators do not meet their needs.

Kornfein remains disappointed with the University’s inaction toward elevator maintenance. “I just think [the University could do] better,” she said.

Vandlik also wrote that students who have elevator issues are encouraged to report by submitting a fix-it ticket or, if urgent, notifying their housing service center. Emergency maintenance is available after hours.

“We appreciate that elevator outages are important to all students, but especially significant for those who need the elevator as an accommodation,” Vandlik wrote. Students are offered more accessible temporary accommodations if repairs cause an issue, she wrote.

“The University is committed to ensuring its facilities, programs and services are accessible to everyone, including those with disabilities,” she wrote.