Editor’s Note: This article is a review and includes subjective thoughts, opinions and critiques.

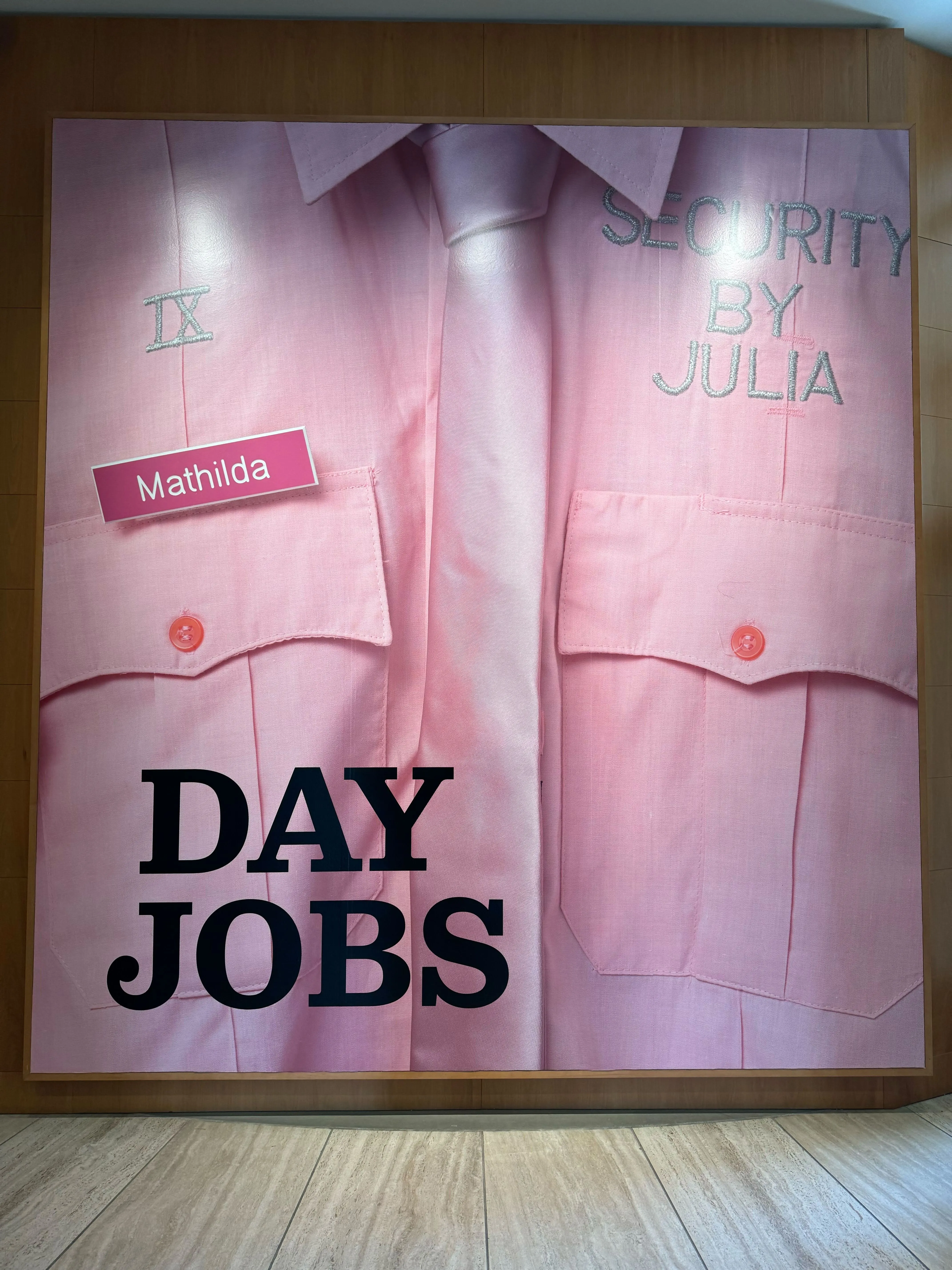

From waiting on tables to working in industry, it is a known reality that artists often take on other jobs to support their creative practice. The Cantor’s newest collection, “Day Jobs,” highlights the unnoticed inspirations these careers can bring to art. The exhibit — which opened on March 6 — posits that the jobs artists take on are not necessarily burdens, but a vehicle for artistic evolution.

“Day Jobs” is extensive: two floors, each with rooms curated by industry or field. This week, I will explore the first floor, celebrating those who work behind-the-scenes in the art world, marketing and service industries.

The first hall honors those who worked within the professional art world, but not as full-time artists themselves. Larry Bell, one of the exhibit’s featured artists, was working as a picture frame shop assistant when he accidentally cracked some glass. He was perplexed by the lines formed by this crack: the glass’s reflection, the shadow of the break and the break itself. He then sold that cracked frame as an artwork, now hanging in “Day Jobs.”

Bell’s work — which also includes laminated glass cubes that change color depending on your viewpoint — is a product of his experience at the frame shop, his day job serving as an unexpected source of inspiration. His art reminds me of the omnipresence of inspiration and beauty, latent yet perpetually available in all corners.

In the same room, “Day Jobs” presents four wall drawings by Sol LeWitt — although the drawings themselves were not painted by him. LeWitt worked as a receptionist and night watchman at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, giving him opportunities to intimately meet contemporary artists. These conversations inspired him toward his unique strain of art: instructions.

LeWitt’s art pieces are, quite literally, instruction manuals themselves on how to exactly create the specific displayed paintings, which were then drawn on by other hired painters. His pieces specify, among other things, each stroke of color, the number of people that should be working on it and what pencils to use. LeWitt’s work challenges the definition of art, and was eventually executed and displayed by the MoMA, his former place of employment.

The exhibit’s next room pays homage to artists who work in marketing and media, another common career path for the artistically-inclined. There was a collection of pieces by Andy Warhol — well known as both a commercial illustrator and one of the fathers of American pop art. A large Chanel ad, screen printed by Warhol, hangs in the room and portrays art and branding as synonymous, raising questions about where one starts and the other ends.

The works of Chuck Ramirez also investigate the intersection of art and consumer culture in the United States. Ramirez worked as a graphic designer for a Texas-based supermarket chain, and frequently photographed objects the stores sold as part of his job. His piece “Whatacup,” an ink print that depicts a huge Whataburger cup, reframes a local cultural icon with the added words: “When I am empty, please dispose of me properly.”

A gay man living with HIV, Ramirez combines the motifs of his jobs with his own identity and mortality. “Whatacup” acts as a delicate message about the devastations of consumerism and HIV, a gradual pollution of one’s environment or body, respectively. The piece is simple yet powerful, a testament to the mundane’s ability to provide forms of expression.

This theme of identity and exploitation is further examined in the next room, celebrating artists working in the service industry. Artist Nariso Martinez worked as an agricultural worker over his summer and winter breaks to pay for art school, leading to his piece “Legal Tender.” This artwork re-imagines the U.S. dollar, painted on cardboard produce boxes; the faint logos of cucumbers and watermelons are still visible.

Whereas U.S. currency displays portraits of our Founding Fathers, Martinez instead paints his coworkers, a memorandum of the agricultural labor that is foundational to our nation. “Legal Tender,” at 23-by-7 feet, is a love letter to those Martinez worked alongside, a keepsake to memorialize agricultural service and a reminder to not neglect, but in fact laud, its laborers.

The service industry room also presents a few pigment prints by Tom Kiefer, who worked as a janitor at Customs and Border Protection (CBP) in Arizona to supplement his passion for photography. He sorted through items confiscated by CBP from migrants and asylum seekers, and began collecting them rather than letting them be trashed, according to the object label.

Aiming to honor these items and their owners, Kiefer began photographing them: toothbrushes, rubber ducks and shoes. These photographs reflect not merely the material goods, but the sacrifices made by immigrants. In Kiefer’s words, he captures the objects’ “lived-in soul.” I found these images haunting, with my unease slowly eroding into the comfort of knowing that these people’s lives and experiences have been carefully commemorated, monumentalized.

“Day Jobs” is as beautifully curated as it is expansive. Next week I will explore the second half of the exhibit, but I urge you to see first-hand the art at the Cantor — the exhibit is open until July 21.