For children who don’t speak English at home, the complexities of English phonetics and spelling can be a perplexing puzzle. But assistance with reading and writing is often inaccessible for lower-income families. Ravenswood Reads, a Stanford program, aims to address this issue across San Mateo county.

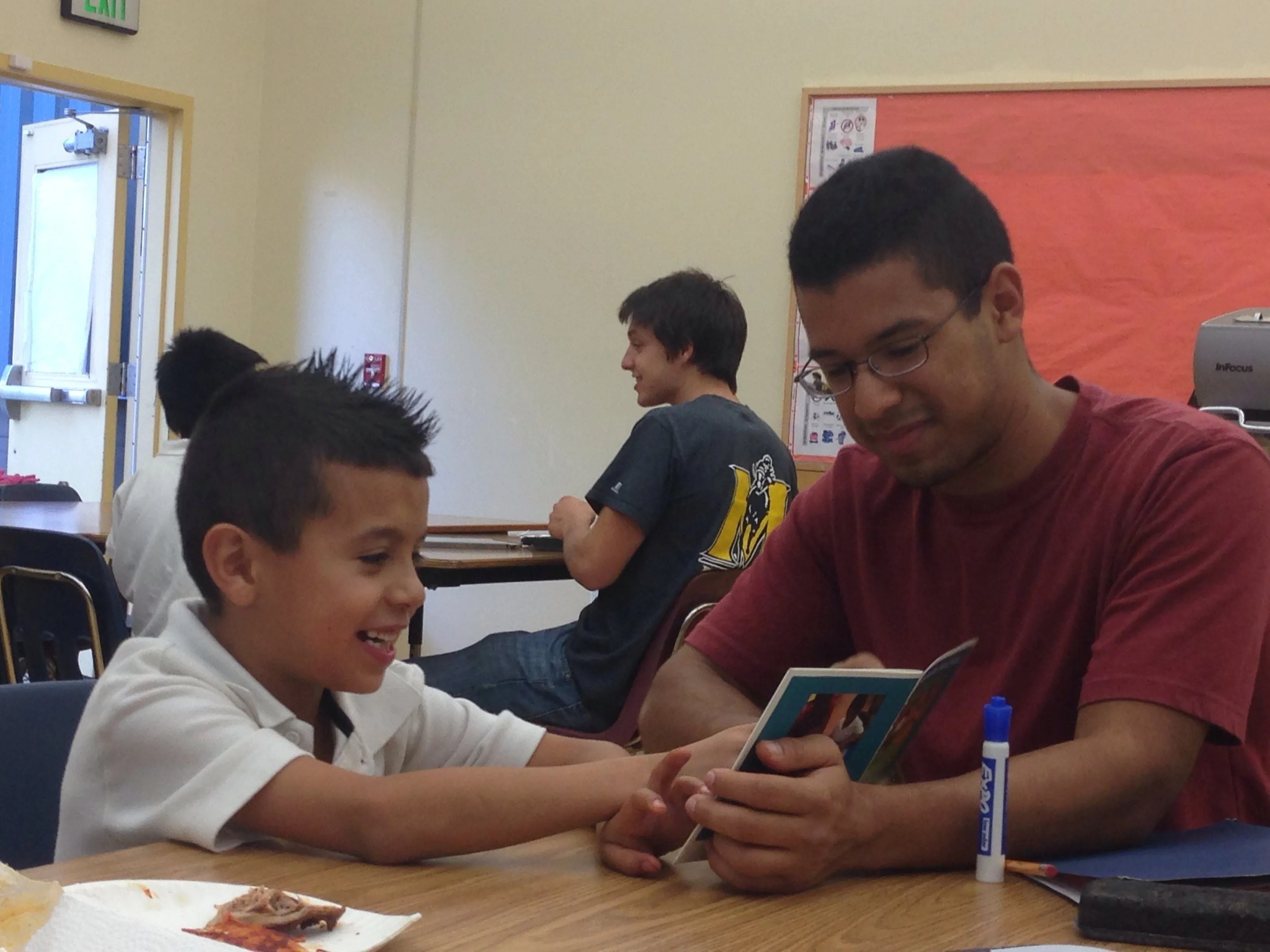

Ravenswood Reads provides literacy tutoring to local children through Stanford’s Haas Center for Public Service. The initiative, which partners with the San Mateo County Libraries system, connects Stanford students with pupils primarily from East Palo Alto and North Fair Oaks. Tutors are paired one-on-one with children, whose class years typically range from kindergarten to second grade, to provide free 30-minute sessions twice a week.

Renee Scott, the Haas Center’s director of early education partnerships, said the program has come a long way since its inception, founded by the superintendent of Ravenswood City School District. The Haas Center got involved after the initially student-led program split off from the school district.

Today, the program’s partnership with San Mateo County Libraries (SMCL) helps volunteers fulfill the needs of families under financial pressure. These families strive to improve their children’s reading skills and seek out more economic options than programs like Kumon, a popular English and math tutoring service. According to Scott, SMCL Community Program Specialist Emmanuel Landa told her that families come in regularly to SMCL, asking where their children could receive reading tutoring.

To tutor with Ravenswood Reads, Stanford students must take the course EDUC 103A/203A: “Tutoring: Seeing a Child Through Literacy.” The class, co-taught by Scott and faculty advisor Rebecca Silverman, discusses existing research on literacy education and practical tutoring pedagogy. The course highlights the importance of supporting students who speak English as a second language or come from diverse backgrounds.

“We encourage tutors to identify texts about kids who look similar or sound similar to [their students], or who live in communities that are similar to theirs,” Silverman said.

Ravenswood Reads tutor Rachel Bong ’27 uses material that aligns with the child’s interests to keep her student engaged. She cited the example of selecting books from the “Dog Man” series by Dav Pilkey since the eponymous character is the child’s favorite. Jocelyn Tran ’25, a Ravenswood Reads fellow, said she occasionally struggles with getting through to non-engaged kids.

“There may be a kiddo who poses as more challenging in terms of their needs, which is totally fine,” Tran said. “It just forces you to be more creative and really think about… making sure that the relationship is productive for both [the tutor and the child].”

Tran, who mentors and supports other tutors, remembers a particular student who took longer to open up.

“She just really did not want to read … whenever a book was brought out, she had a negative reaction to it,” Tran said.

However, the tutor’s persistence resolved this challenge by the end of the quarter, and the student “ended up loving books. It was a complete 180 from the very start, when she would hide under the table when it was reading time,” Tran said.

Much of the challenge for Ravenwood Reads as a program lies in logistics and scheduling, Silverman said.

“[We] help student [volunteers] manage time, create schedules, ensure that they’re able to focus on assessing kids and finding materials that are appropriate for kids. All the while, they’re attending classes themselves,” Silverman said.

Scott also noted transportation difficulties, as both volunteering sites are near traffic-heavy locations. This results in lengthy travel times, taking close to an hour on some days to arrive.

At times, Ravenswood Reads’s pedagogy challenges tutors’ existing notions of teaching. Tutors may come from an educational background where teachers approach their job “like forcing knowledge onto a kiddo,” Tran said. However, Ravenswood Reads prioritizes an interactive and collaborative approach by building on what the child already knows, Tran said. The program offers support to their volunteer tutors in making the transition.

Although Stanford tutors may initially be nervous about the role, they end up forming strong bonds with their tutees — many children stay with the program for multiple quarters or years.

“By the end, they are sad to leave the students, and often both them and their tutees are hugging and crying, sad to tell each other goodbye,” Silverman said.

Part of this bond is built from the joy in seeing tutees improve and build confidence for Bong.

“[My student] was able to spell more words correctly and read more letters correctly. It really made me happy just to see that growth,” Bong said. “She was more comfortable saying, ‘Oh, I want to read the more difficult book’ or ‘I want to do more challenging activities.’ Seeing her want to embrace these challenges was really rewarding for me.”

At the end of each quarter, Stanford tutors gift handmade books to their tutees. This often reveals the intricacies in connections between tutor-tutee pairs, Silverman said. The faculty advisor recalls a tutor made a bilingual book for her tutee.

“You could tell that in their relationship, they had used both English and Spanish to make that connection with each other and share their similar kind of background, identity and interest[s],” Silverman said. “That was really cool.”

As the volunteer tutors forge bonds with the program participants, the importance of reading and writing cannot be understated for Silverman. The skills build the foundation for other fields and professions, really opening doors.

However, the children aren’t the only ones who benefit. Tran noted that the relationship is reciprocal, helping volunteer tutors also discover their love for teaching. The class often inspires program volunteers to continue teaching in some form.

“We’re learning so much from them, as much as they’re receiving from us, so it goes both ways,” she said. “We find that tutors are interested in fields of education or somehow supporting education or being involved in education beyond their time in the class.”

Correction: A previous version of the article misattributed information about parents coming into SMCL to Emmanuel Landa as a direct quote. A previous version of the article also misstated that Jocelyn Tran’s graduation year was 2024 rather than 2025. The Daily regrets these errors.