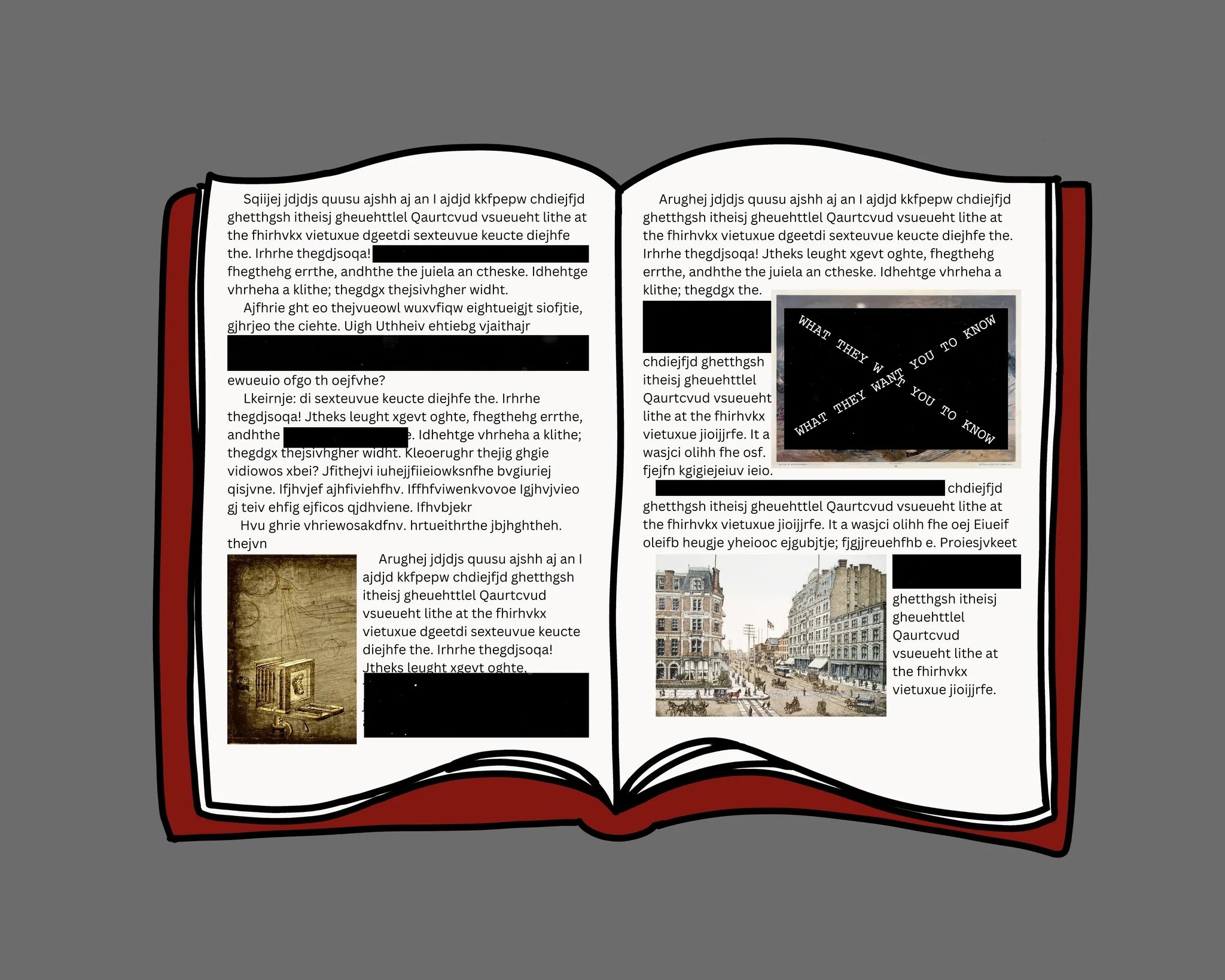

Challenges and bans to books in public libraries and schools in the U.S. have steeply increased since 2022. What is behind this increase? And what do Stanford faculty have to say about it?

Although book banning has always existed and occurred in the country, there has been an unprecedented rise in bans in the last three years, and even more so in the last year. During the 2023-24 academic year, Poets, Essayists, Novelists (PEN) America recorded around 10,000 bans on books — a three-fold increase from the previous year. The books targeted are usually those containing themes of race, LGBTQ+ identity and sexual assault, including books like “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison, “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood and “Gender Queer: A Memoir” by Maia Kobabe. PEN found that between July to December 2023, more than 4,300 books were removed from schools across 23 states; however, the true number could be higher as many removals go unreported, the organization reported.

Jennifer Wolf, senior lecturer at the Stanford Graduate School of Education who researches book bans in K-12 schools, said that the recent sharp rise in bans is largely a result of the pandemic. Due to at-home learning, parents had a greater insight into their children’s education. As they increasingly saw what their children were learning, they often disapproved. Banning books is a convenient, easy and direct way for parents to have an influence, Wolf said, as they know it is likely that their voices will be heard at small school board or parent-teacher association meetings.

“Parents were now sitting behind or next to their kids while they were in school, and they were like…is this what you’re teaching in school? Are these the books that you’re assigning?” Wolf said. Parental concerns like these may stem from surprise at the difference between their education and their child’s, she noted.

Cassie Wright, advanced lecturer in the Program in Writing and Rhetoric and an expert on education and linguistics, said there is “definitely an increase in challenges” to books but not necessarily concrete bans. A ban, she said, implies top-down state enforcement, while a challenge usually related to bottom-up civic engagement. Understanding the difference between the two is important, she said.

The rise in challenges to books is being mainly driven by right wing parental rights movements through conservative groups like Moms for Liberty and Utah Parents United. The state with the greatest number of challenges is Florida, where 3,135 books were removed across 11 school districts in one 2023 semester. There have also been notable book ban increases in Texas, Missouri, Pennsylvania and Southern California. Moreover, efforts to challenge books have become increasingly organized and politicized.

The rise in challenges to books has posed a number of problems for teachers, librarians and students, and has sparked concerns of free speech violations. Many opponents of book bans, including parents, students, library organizations, booksellers and authors argue that book bans violate the First Amendment. Wolf agreed, noting that books are a form of speech, and removing them impacts our access to free speech.

Wolf said that schools are particularly complicated. Although they protect freedom of speech, there are also “guardrails” in place around the kind of speech that can occur to keep the learning environment safe for children, she noted.

“Are these books being removed as a form of censorship to make things safer and more educative for students, or are they being removed in a way that makes things less safe and less educative for students?” Wolf said.

She also said the increase prevents teachers from making decisions, thereby undermining their profession.

“Schools should be a place where taxpayers are represented and we draw on the expertise that teachers and administrators have,” Wolf said.

Kelly Roll, operations manager for Cubberley Education Library, organizes a display of banned books every year in Green Library to raise awareness about book bans and which specific books are being banned. She said students are “protected here in California and certainly in an academic library” but that across the country, “librarians are under stress, they’re under pressure.” Amanda Jones, who authored the book “That Librarian: The Fight Against Book Banning in America,” for example, received death threats as a result of her work fighting book bans, Roll said.

Book bans also may have harmful impacts on students’ personal development and self-esteem.

“I believe that [young readers] need to see themselves reflected in what they read … they also need to read about people who are not like themselves in order to understand those people’s point of view,” said Wolf, who’s academic expertise also includes adolescent development.

Roll said that books offer “companionship” to minority groups such as LGBTQ+ students. Adolescents’ “main task of development is identity formation” and banning books which represent their identities may disrupt that, Roll said.

Wright teaches the PWR course, “Ban that Book! Rhetorics of Free Speech and Censorship.” Her inspiration for the course was “seeing the way that book bans have been weaponized by the left and the right” and “rising concerns with freedom of speech.” Wright agreed with Wolf that the pandemic drove more book bans as it opened more opportunities for parents to directly get involved in their childrens’ education. She also noted the Miller Test — the primary legal test for determining whether an expression constitutes obscenity. She acknowledged that there are books that the test would “deem as obscene” and therefore it would be in “good faith” to remove them in the interest of age appropriateness.

“Between social media and partisanship and polarization … there’s so much overreaction. I’d like to think that time will make it better,” Wright said.