At first glance, “Woven Narratives: Textiles as Living Archives” is a museum exhibition about fabric. But step closer, and it becomes something much more intricate. Behind every stitch and fray lies a story of identity, labor, memory and survival.

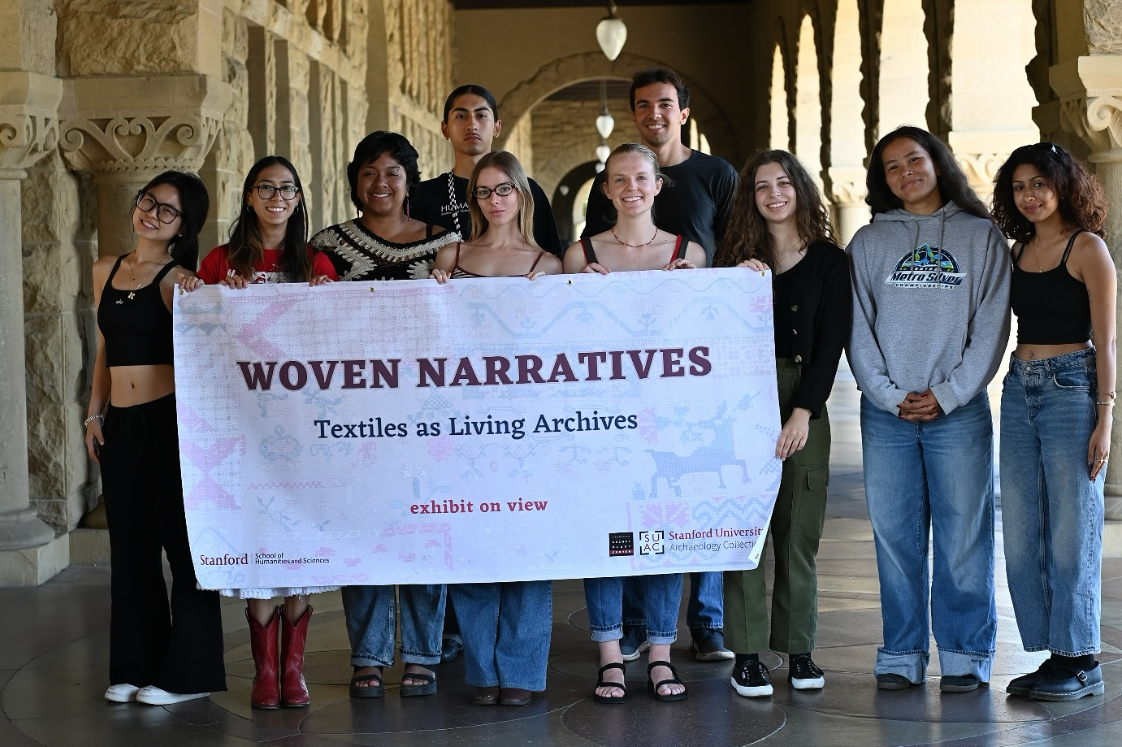

Curated by students from ARCHLGY 134: “Introduction to Museum Practice” and former assistant director of archeology collections Danielle Raad, the exhibition is the latest in a series of student-curated exhibits organized by Stanford University Archaeology Collections (SUAC), which oversees the curation and care of archaeological materials on campus.

The project features textiles and textile-related tools from Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, Thailand, Japan and the Philippines — all drawn from SUAC. While the pieces vary in material and design, each invites visitors to reflect on how clothing, fiber and craftwork are far more than everyday objects. They’re personal and political archives, items we wear on our bodies but that carry generations of meaning.

Located at the Stanford Archaeology Center, the exhibition opened to the public on June 2, and is viewable until April 15, 2026. The exhibit officially previewed with a public celebration on May 30 at the Stanford Archaeology Center. The celebration included remarks from curators, interactive textile-themed activities, a sticker sheet drop and even custom cupcakes.

Veronica Jacobs-Edmondson, a Senior Collections Assistant at SUAC, described the mission of the exhibit.

“We wanted to do something completely different than our previous exhibit on ceramics from Indigenous West Mexican communities,” Jacobs-Edmondson wrote in an email to The Daily, referring to the “De la Tierra” exhibition.

In early brainstorming sessions, she and colleagues found themselves repeatedly returning to the same subject: textiles. Together, the staff sorted through hundreds of objects in SUAC’s collection, selecting a longlist based on their aesthetic quality, condition and cultural or historical relevance. Students then chose which items to research and curate into cohesive cases.

Anusha Nadkarni ’27 co-curated “Weaving Womanhood,” a case focused on the Asháninka people of Peru and Brazil. At its center is a baby sling, known as a “tsompirontsi,” which Nadkarni described as “woven with specific patterns to indicate that the wearer is a woman” in an email she wrote to The Daily. The sling is adorned with carved bones that, when clinked together, produce a sound intended to soothe the baby carried inside.

According to Nadkarni, the curatorial process involved deep research and careful consideration about how to represent the object without reducing its cultural context.

“One challenge from this process was navigating our positionality as outgroup members approaching personal and cultural practices from an academic perspective at an elite university,” she wrote. This critical awareness of power, distance and interpretation became core to the exhibit’s final form.

Alex Turner ’26, Nadkarni’s co-curator on “Weaving Womanhood,” shared a similar sentiment. Initially drawn to the baby sling because the bones seemed to him like symbols of death, a jarring choice for an object meant to carry new life, Turner came to understand that his instinctive interpretation wasn’t culturally universal.

“Eventually, I realized this symbolism isn’t inherent across cultures and was likely not apparent to the object’s Asháninka creators,” Turner wrote in an email to The Daily.

According to Turner, one of the most rewarding aspects of the project was grappling with the ethical responsibilities of museum curation. This included “practical challenges like arranging objects in a way that makes them more accessible for the viewer or more theoretical ones like ethical collection and presentation of potentially looted objects.” Working with real artifacts challenged him to think critically not just about the items themselves but about the systems through which they were acquired, studied and displayed.

Their section explores how gender influences both the creation and use of Asháninka textiles. The sling itself is a gendered object: while women weave the fabric, the bones are carved by men. It’s used by mothers to carry their infants and, in some cases, the bones may be inherited, passed down from one woman to another.

Nadkarni said the turnout exceeded expectations, with more than 100 attendees engaging with the student-created cases.

While “Woven Narratives” draws from a wide geographic range, many of its themes feel relevant and resonant far beyond their specific origins.

For Nadkarni, the exhibition aims to prompt introspection about how textiles reflect our own lives, the clothes we wear, the stories we inherit and the systems we participate in.

“Textiles play a role in all of our lives and are especially relevant as a practice that has experienced colonial erasure, labor exploitation and gendered implications,” Nadkarni wrote. “I hope visitors spend time confronting the relationship between textiles and their own sociopolitical existence.”

Jacobs-Edmondson said she hopes the exhibit leaves audiences with a sense of care and curiosity, to “think of their own belongings in a more deliberate way.” Raad shared a similar sentiment.

“Textiles are archives of heritage and identity, technique and style, oppression and resistance, and relationships among people and between people and environments,” Raad wrote.