On Saturday, Jan. 3, atop the Santa Cruz Mountains overlooking Stanford, the heavens mourned. Rain and wind bent the trees like the wind-swept cypress of Persian poetry, that ancient symbol of resilience and grief. Hundreds gathered on the hillside, while thousands more across the world wept in their own solitude. They had come to honor Bahram Beyzai: writer, director, playwright, poet, scholar, teacher, father, brother, husband. He was a polymath in every sense, demanding a breadth of talent rarely seen today.

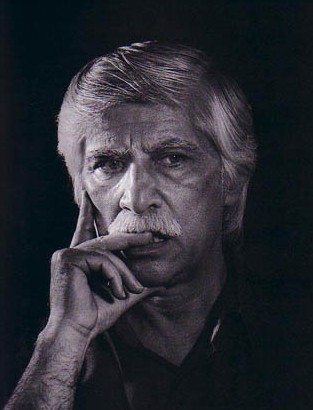

I myself had the privilege of witnessing how he could seemingly manipulate time: in one unforgettable lecture at Stanford, Beyzai distilled 3,000 years of Persian literary and moral history into a single hour, and it felt as if everything beyond that room simply ceased to exist. Even in casual conversation, his deep-set, intense blue eyes projected wisdom and passion. After his passing, his wife Mojdeh Shamsaie movingly wrote that the sky itself seemed “colorless” without the light of Beyzai’s sky-colored eyes.

Widely recognized as one of the greatest Iranian cultural figures of our time by scholars and artists alike, Beyzai’s name belongs alongside legendary figures like Ferdowsi and Dehkhoda, titans who preserved Persian across centuries. Like Ferdowsi, who rescued the language through his epic Shahnameh, and Dehkhoda, who catalogued its vast lexicon in a 200-volume dictionary, Beyzai devoted his life to safeguarding Iran’s cultural soul. But he understood that culture survives not through archiving alone but through constant reimagining, through making the ancient speak urgently to the present.

As a pioneering filmmaker, Beyzai revolutionized Iranian cinema by weaving ancient mythology into modern narratives. A leading figure of the Iranian New Wave, he used cinema as a modern extension of classical storytelling. His masterworks — Downpour (1972), Ballad of Tara (1979), Bashu, the Little Stranger (1986) — intertwined Iranian history and contemporary social issues. Bashu, a poignant story of a war-displaced boy, was later voted the greatest Iranian film of all time by 150 Iranian movie critics. But these were more than films, they were acts of cultural archaeology, excavating Iran’s pre-Islamic consciousness and demonstrating how buried stories could illuminate modernity’s moral crises.

In the theater, Beyzai was both innovator and resurrector. He delved into Iran’s pre-Islamic and folk performance heritage, researching traditional forms of passion plays to formulate a boldly non-Western identity for modern Iranian theater. His plays, including The Death of Yazdgerd, bridged ancient ritual and contemporary stagecraft. Some critics regarded him as the greatest playwright in Persian, earning him the sobriquet “the Shakespeare of Persia.” Yet this comparison, while flattering, obscures what made Beyzai unique: where Shakespeare invented modern psychological interiority, Beyzai recovered an older form of dramatic consciousness, one that was rooted in ritual, myth, and collective memory rather than individual subjectivity. His theater performed the work of cultural continuity itself.

Beyzai’s academic work was inseparable from his art. Namayesh dar Iran (A Study on Iranian Theatre), published in the mid-1960s, remains the definitive text on the history of Iranian theater. Over his career, he authored nearly 70 books and 14 stage plays, an astonishing output that attests to his prolific intellect. Perhaps most remarkably, he was a master of Persian prose itself. His writings demonstrated the language’s extraordinary expressive range, moving effortlessly from archaic epic diction to colloquial speech with unmatched eloquence. This linguistic virtuosity embodied Beyzai’s deeper conviction that within the layers and registers of the Persian language lay compressed the entire history of Iranian thought and feeling.

Despite his towering status, Beyzai faced incessant censorship after the 1979 Revolution. Many of his films and plays were banned or hampered by authorities, and in 2010, after decades of such pressures, he departed Iran. The irony was bitter: a man who dedicated his life to preserving Iranian culture was forced into exile by those who shamelessly claimed to be its guardians. He accepted an invitation from the Iranian Studies Program at Stanford University and became the Bita Daryabari Visiting Professor of Iranian Studies. For the next 15 years, he devoted himself to teaching and mentorship in exile, introducing students and global audiences to the riches of Persian culture. His courses on the history of Iranian performing arts were legendary, and those who experienced his presence understood that they were encountering a conduit to something far older, a living link in an unbroken chain stretching back through millennia.

The timing of his death carried its own symbolic poetry. He passed away in California on Dec. 26, 2025, on his 87th birthday. By the Iranian calendar this date is the 5th of Dey, a day officially designated as Playwrights’ Day in Iran in honor of his birth. In leaving this world on the very day it celebrates him, Beyzai gave one last, poignant performance. Perhaps it was fitting that a man who spent his life collapsing temporal distance, making the ancient contemporary and the contemporary eternal, should exit precisely when past and present aligned.

As the rain fell that Saturday and the memorial gathering dispersed, one could sense that an era had closed. Yet Bahram Beyzai’s influence lives on in every story, play and film that bears his imprint, and in every student who walks inspired in his path. His true legacy may be this: in an age of cultural amnesia and accelerating fragmentation, he demonstrated that depth of memory is not a luxury but a necessity, that a people disconnected from their cultural wellspring risk becoming strangers to themselves.