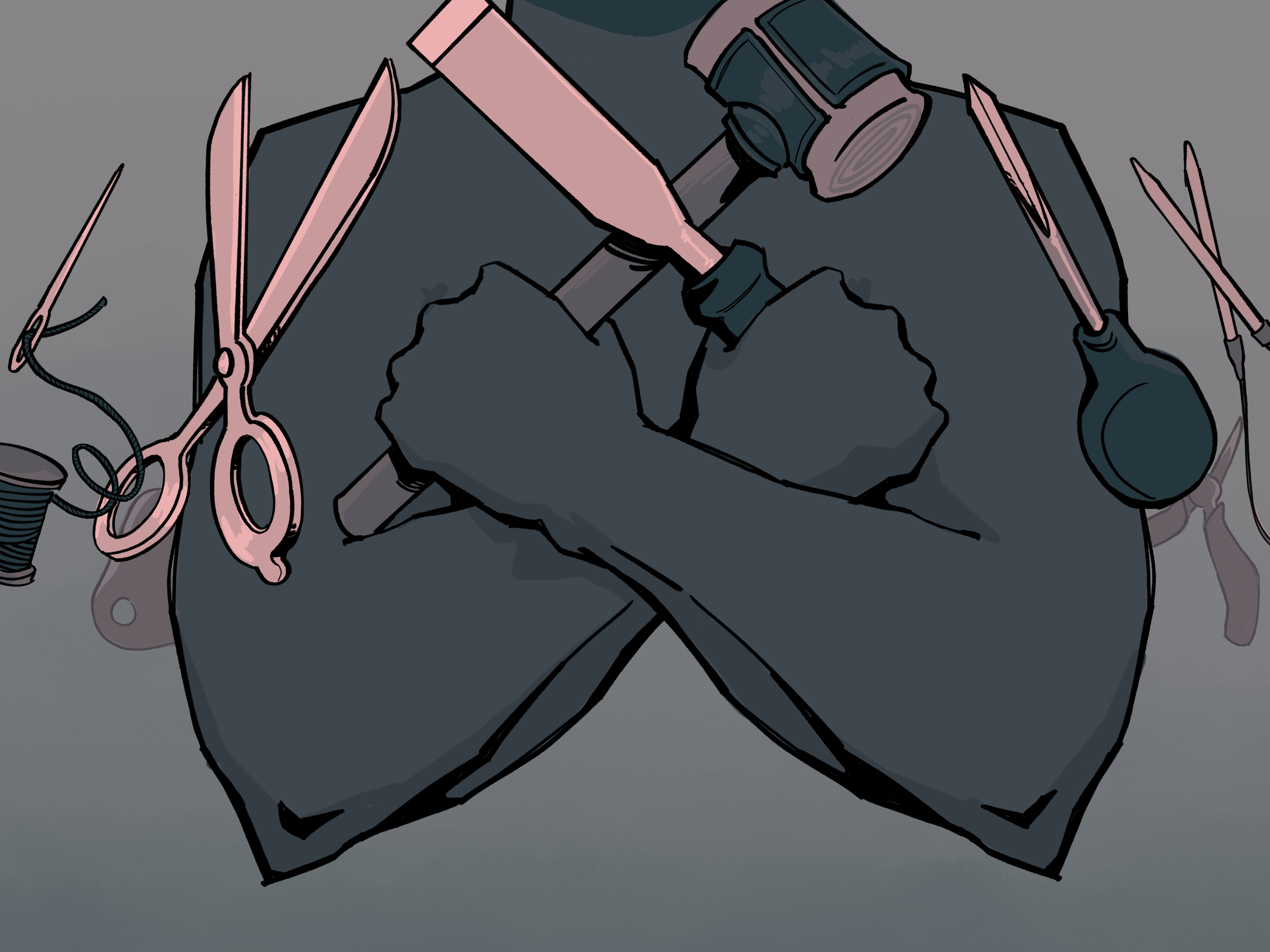

In “Culture of Craft,” Quinn Cook ’29 documents the culture and people engaged in the crafts and practical arts and what we might learn from them.

When most people think of “crafts,” usually within the irreversible binomial of “arts and crafts,” they picture hot glue, safety scissors and plastic googly-eyes. “Crafts,” to them, are the domain of popsicle stick frames and pipe cleaner eyesores destined to hang on the refrigerator door. It is, in short, the amateurish slop that falls increasingly out of vogue as a Mother’s Day gift after its creator becomes a teenager.

As a leatherworker, though, the relegation of “craft” to the rank of kindergarten activity is completely antithetical to my understanding of it. Craft, to me, is about a particular kind of embodied knowledge. It is the slow accretion of skill that can only come with time and intention.

The distinction, crucially, isn’t material — it doesn’t matter whether the craft’s medium is wood, felt, metal or ceramics. I will even go so far as to admit that some cotton-ball creations (only very few, mind you) are worthy of admiration. Craft, at its core, is about taking the time to do something well for its own sake. It demands the kind of patience and intense effort that glitter dust and Elmer’s glue don’t often encourage.

If craft is really about craftsmanship in the process of making, then it is no wonder we have slowly lost touch with its original definition and let it drift into the realm of elementary school busywork. Craftsmanship, in its original form, requires taking the time to finish your work with a dozen different grits of sandpaper. It requires design iteration. It requires deep knowledge in a specific area that is applied slowly: all things eschewed by modern work culture.

And why, after all, should we have that deep knowledge when AI chatbots and “expert systems” can now collate and recall information far better than we can? Why commit to a single domain when we have so much potential in a dozen others, too? Why iterate the same project, over and over, when it works “just fine” already?

If you can’t answer that yourself… well, maybe this column isn’t for you. Or, maybe it’s exactly for you. The aim of this column is to document the culture of craft, not just its manual execution. That often goes against the grain of the entrepreneurial “hustle culture” we find ourselves in most days. Though they can be harder to find at a place like Stanford, I believe that there is just as much — if not more — to be learned from the machinist, potter or carpenter, as from the CS major.

When I began leatherworking some years ago, I admit that I, too, was impatient and somewhat naïve. I had seen a few YouTube videos and, true to fashion, thought, “I could do that.” As many academically successful students do, I read voraciously and watched endless tutorials to try and absorb as much as possible. I learned about the tanning of leather, the grain structures of hides and the difference between a Japanese and French skiving knife. I learned everything, that is, besides how to actually craft.

Here at Stanford, this kind of abstract learning might just fly. It might even be rewarded. As our lives — academic, social and otherwise — move increasingly onto screens, the product of our work is rarely physical, and even less frequently does it stand alone for judgment. With craft, however, book knowledge counts for very little. Craft exists outside of its creator, exposed to the raw, aesthetic evaluation of anyone who sees it, no marginal comments attached.

In order to physically instantiate something that can defend itself against scrutiny (without the help of a salesman or blingy website), one must hone their craft. The angle of my knife, the force behind my maul, the cut of hide I use — I may see the mistakes in the final product, but constant practice won’t fix them.

So, don’t let your gung-ho, Silicon Valley “bias towards action” mindset fool you. When you create, give the work space to breathe. When you have the fruit of your labor in front of you, treat it as German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer encourages in The World as Will and Representation: waiting to see whether it will speak, and if it does, what it will say to you. If it whispers about a flaw, don’t try to speak over it in hopes that no one else will hear. Listen attentively, and begin a dialogue. That is the culture of craft.

College, in one narrow sense, is a crossroads where one must decide whether “MVP” stands for “Most Valuable Player” or “Minimum Viable Product,” whether to stay a journeyman for life or to become a master craftsman of one’s own. Whatever your discipline of choice — be it woodworking or writing, leatherworking or LeetCode — I encourage you to engage with it as craft.