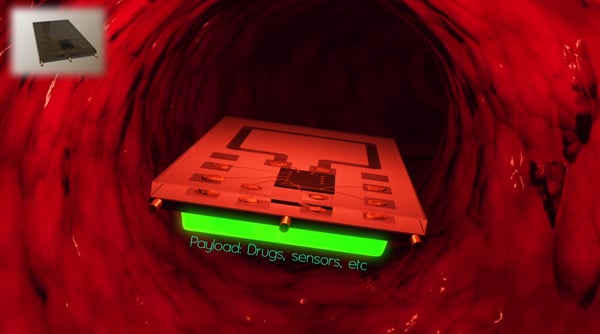

Medical promises of the future, from implanted microchips that help in operations to full nanoscale surgeries with single-cell precision, just got a lot closer to reality. Stanford electrical engineering researchers have developed a microchip that can swim through fluids while powered and controlled wirelessly.

At three by four millimeters, the chip is smaller than Lincoln’s head on a penny, giving it the potential for important medical

applications. The chip is in the engineering research stage right now, but holds promise for practical uses in the future. With further development, medical engineers could theoretically outfit the chips to transmit data from inside a patient’s blood stream, enabling precise testing, or to dispense medicine to individual cells, enabling precise treatment.

Mechanical or electrical implants are no rarity in medicine, ranging in applications from prostheses to pacemakers. However, they have met limitations from battery technology, which generally progresses more slowly than electrical circuit technology. Batteries are also large and heavy, and they require changing.

However, this new research, presented by Electrical Engineering Professor Ada Poon at the International Solid-State Circuits Conference on Tuesday, holds promise for a whole new category of medical devices that don’t rely on batteries for power. Poon’s team specializes in wireless power, something previously thought impossible for transmission through human tissue.

The team’s initial breakthrough came from advancements in engineering mathematics that they released in 2009. The research questioned the previous assumption that only low-frequency light could move cleanly through human tissue.

“The original research for this happened in the 1960s,” Poon said. “Then, in the 1980s and 1990s, circuit designers just took these results, and they decided these circuits … only worked around 10 megahertz.”

By reconsidering one term in one of Maxwell’s equations, which in physics represent the mathematical definition of light, Poon’s research indicated that much higher frequencies of light could diffuse cleanly through various human tissues. Thus, wireless power with frequencies on the order of television or cell phone waves could be used to deliver power.

Higher frequencies mean smaller receiving antennas and, therefore, wireless power delivery to miniaturized devices.

The next breakthrough came in finding an alternative method for locomotion in a fluid.

Previous methods included using small electric motors, but these were still up to 15 centimeters in length — far too large for an implant. Poon’s team developed a system that uses electromagnetic induction to roll the chip in the fluid, generating motion in a similar manner to a kayak or a freestyle swimmer as it gently rolls in the water.

A few other developments, including a low-power wireless data transmission link, played roles in the research as well.

The product of this research, Poon’s chip, moves very slowly through fluids based on remote controls and receives all its power wirelessly.

Poon said that applications for the technology will come both relatively soon and far in the future.

In the short-term, Poon’s team is in conversations with doctors to use the moving chips to guide catheters into position for precise operations. The vision for this system would involve outfitting the tips of catheter tubes with locomotive chips to fine-tune their movement.

Another potential project for the team’s research involves sending these remote chips into a patient’s coronary arteries equipped with sensors. Swimming several of these sensors to strategic locations in the heart could transmit data with enough precision to make a map of the heart’s activity and detect irregularities.

This application would require much more development for control and movement of these chips, a current focus for Poon’s team. She described this possibility as “middle-term” in the development of the device.

The long-term and most significant applications of this technology will require much more development. Poon stressed that to really change medicine, the chip would need to be able to get feedback from its surroundings and, for example, turn itself around if it hits a bloodstream wall.

“If we really want to make it a robust system, we have to add a feedback system,” Poon said.

When more advanced feedback systems become possible on the physical scale of Poon’s current project, more application will come into play.

Among the most important of these, Poon said, would be drug delivery on a level of precision well beyond our current capabilities, even down to the single-cell level. This dream, however, would require answering other big questions, such as how to make a cell accept a microchip without dying.

“[Drug delivery] is much longer-term,” Poon said. “For now, we want to make it into short-term, mid-term and long-term applications.”

Teresa Meng, an electrical engineering and computer science professor, and Daniel Pivonka and Anatoly Yakovlev, doctoral-level student researchers, also contributed to the work as members of Poon’s research team.