“From 2008 onwards, the world has really changed economically,” said Nick Bloom, professor of economics. “Policy uncertainty probably wasn’t a big deal before.”

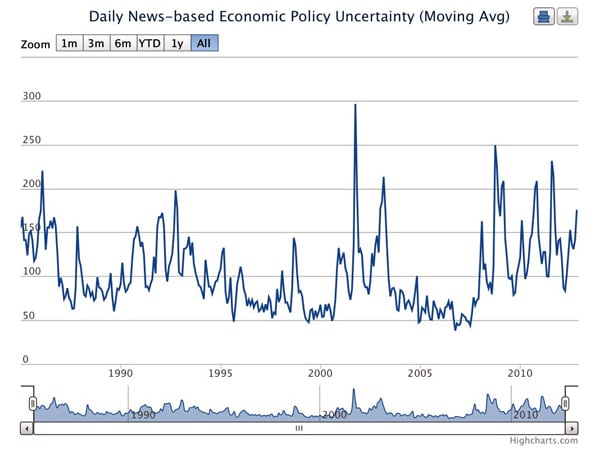

In fact, since 2008 economic policy uncertainty has averaged about twice the level of the previous 23 years, according to the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index created by Bloom, Scott Baker, a fifth-year doctoral student in economics, and Steven Davis, professor of economics at the University of Chicago.

“Policy uncertainty has to do with uncertainty that consumers and businesses have about the actions that policymakers take and what effects those actions or what effects those pieces of legislation will have in the future,” Baker said.

They found that policy uncertainty is at its highest levels in history, with the nearest parallel in U.S. history being the years during the Great Depression.

Causes for this uncertainty are as numerous as they are daunting.

“It’s been a whole series of events,” Bloom said. He listed everything from monetary and fiscal policy like interest rate cuts, the stimulus, the debt ceiling and the fiscal cliff, to the Affordable Care Act, the outcome of this year’s elections and the European sovereign crisis — all of which are causing economic angst.

Economic policy uncertainty can have serious macroeconomic effects, according to the researchers.

“The history of the recession is really from late 2007 to mid 2009. Normally we expect to come down and come back up, but now it’s just gone down and continued. And increasingly people have blamed this on policy uncertainty,” Bloom said.

The reason for this sustained economic stagnation is that investment and, to an extent, consumption suffer when there is uncertainty.

“A massive number of people are waiting,” Bloom said. “The typical investment dollar that is spent in the U.S. is spent by large firms, [which] are very forward looking… They’re super sensitive to policy uncertainty.”

Reducing economic policy uncertainty can be a challenge, particularly in the current political climate.

“With polarized parties but balanced power, it means you’re exposed to big swings,” Bloom said.

Both Bloom and Baker agree that political compromise is necessary to lower policy uncertainty.

“I think politicians being able to come to a compromise here is important, but also not only in dealing with this but also signaling that they can potentially compromise more in the future,” Baker said.

For Bloom, the problem will be more difficult to solve.

“I’m pessimistic and the reason is, if you look at what’s the ultimate cause of policy uncertainty in the U.S, it’s over the budget. There’s a big budget deficit and we have to close it,” he said.

“Congress being at loggerheads or being deadlocked, it doesn’t just bode poorly for the next few months, but as we get closer and closer and there’s no deal being met closer to the fiscal cliff, closer to a debt crisis, things like that, people begin to potentially lose faith in the ability of politicians to compromise in the future,” Baker said.

The researchers use three indicators to model the index: economic forecaster disagreement, tax code expirations and news articles about economic uncertainty.

The indicators were chosen specifically to capture different parts of policy uncertainty, through both objective and subjective measures. Forecaster disagreements reveal information about government spending and monetary policy at the federal and state levels, tax expirations capture the increase in temporary legislation and the news index is more general, Baker said.

“It’s basically predicated on the notion if there is more policy uncertainty present, then newspapers are going to write about it more,” he said. “It reflects what’s going on. It’s not a perfect measure, though, but I think it’s a pretty good one.”

Bloom, Baker and Davis have also applied this metric to Europe and Canada. They are looking to expand it to Latin America, China and other Asian countries.