As we enter the holiday season, many of us will inevitably find ourselves in a big-box retail store to satisfy our consumer wants and needs. One of the top destinations across America will be Walmart, the largest retailer in the world. Walmart’s questionable business practices are well documented; these range from labor issues — providing extremely low wages, locking in retail employees, purchasing from foreign suppliers that abuse human rights, and more — to community issues, such as the fact that competing local stores will often go out of business.

Many acknowledge these issues, but ultimately conclude that Walmart is a normative good, as it is what the people want. Yet this logic is fundamentally flawed, due to the economics of the multi-person prisoner’s dilemma (if you are unfamiliar with the prisoner’s dilemma, I suggest briefly glancing at the Wikipedia page for a quick introduction). One example of a multi-person prisoner’s dilemma involves conservation: If there is a water shortage, everyone should conserve water. But if everyone conserves water, there is no need for you (one individual) to conserve water. Since everyone else has the same incentive to defect, it is everyone’s individual best interest to not conserve water. And once no one conserves water, it is futile for you to attempt to conserve water.

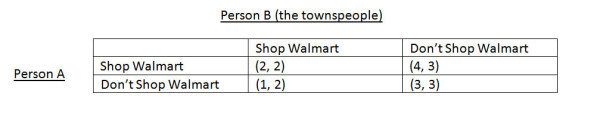

In applying this analysis to Walmart, I will make four assumptions. The first is that a person gets one point of utility for shopping at a downtown retail store, while he gets two points of utility for shopping at a Walmart on the outskirts of town. Walmart offers a combination of low prices and diverse products, which for many shoppers outweighs the fact that local stores often offer superior customer service. The second assumption is that a person derives two points of utility from the existence of a vibrant downtown retail sector, regardless of how often he consumes there. For middle and upper-class communities, this appears reasonable (think of how much one saves by shopping at Walmart versus how much one would pay to live near a vibrant downtown). Although the above utility payoffs are purely hypothetical, they may be relatively accurate at a rough level for certain groups of people.

The third assumption is that person B is representative of all the other townspeople: If person B decides to shop at Walmart, many Main Street retail stores will shut down (yet if he shirks Walmart, Walmart will remain open due to business from neighboring towns). Studies have shown that the success of Walmart is inversely proportional to the success of local retail stores, so this assumption makes sense as well. The final assumption is that person A’s decision has no bearing on what person B decides.

Given these assumptions, we would have the decision matrix as shown below, where (X,Y) is the payoff to person A and each of the townspeople, respectively:

Person A’s dominant strategy is to shop at Walmart, as no matter what person B decides, person A is better off adopting that strategy. All the townspeople, though, are faced with this same decision matrix; they will all at some point be person A, deciding whether it is in their best interests to shop at Walmart. If each has the same payoff schedule, then the outcome is clear: Everyone will defect and shop at Walmart, even though collectively this fails to maximize net utility. The utility maximizing outcome would be semi-restraint, or just enough people shopping on Main Street to keep the downtown vibrant. Given the free-rider problem, though, this outcome is far from guaranteed. The next best outcome, then, is for no one to shop at Walmart.

In essence, this has become a collective action problem. Individually, people are best off with a Walmart that no one but them frequents. But since everyone has this incentive to free-ride, collective action is necessary if we want to maximize the community’s utility. Relevant collective action strategies include boycotts of existing Walmarts, shaming people who shop at Walmart despite having little economic need, and rallying municipal governments to oppose the development of new Walmarts.

This piece is not meant to provide a conclusive empirical analysis of why we should oppose the existence of Walmarts. Rather, it attempts to show how an action that is in the best interests of the individual can be sub-optimal when viewed on a collective level. It is a popular saying that “since everyone shops at X, X must be good for the community.” The realities of the multi-person prisoner’s dilemma, however, question the validity of this logic.

What are your consumption plans for this holiday season? Let Adam know at [email protected].