“IN SOUTH AFRICA COLONIAL SLAVERY CONTRIBUTED TO A SOCIETY BASED ON RACIAL OPPRESSION... In the later 1800s the demand for cheap labor by the mining industry entrenched segregation and promoted a low-wage society which greatly benefited ‘white’ South Africans.”

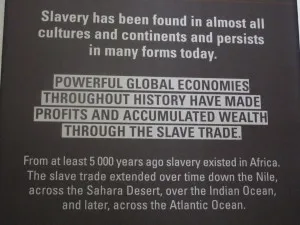

“POWERFUL GLOBAL ECONOMIES THROUGHOUT HISTORY HAVE MADE PROFITS AND ACCUMULATED WEALTH THROUGH THE SLAVE TRADE.”

“Slaves living at the Cape were emancipated on 1 December 1834,” a third display said, before adding: “BUT THEY WERE NOT FREED.”

Such were the words I read on three displays in the foyer of the Iziko Slave Lodge Museum in Cape Town two weeks ago.

Taken together, this narrative is the most explicit connection I have seen a publicly funded institution make between former and modern-day racial oppression, class exploitation and multinational enterprises.

With these displays in mind, I expand upon the ideas I raised in last week’s column “Overcoming the Racist State.”

The more refined questions I seek to ask are:

Why do institutions that enabled structural inequality under slavery, apartheid or Jim Crow remain unchanged after such systems become illegal? How can we expect to eradicate structural inequality when oppressive structures remain firmly intact?

The South African apartheid regime enacted a series of zoning laws by race. In Cape Town, the regime evicted all Coloured and Black people from valuable land in and around the city center, demolished their homes and relocated them to sandy plains far outside the city.

The result today?

(C/o National Geographic)

A segregated Cape Town geography that features mostly white people living in the condos and villas near the city center and along the city’s beaches, while the majority of the Coloured population lives 20 miles outside Cape Town in the township of Mitchell’s Plain and the majority of black Capetonians are relegated even further to Khayelitsha (now the fastest growing township in South Africa), many living in informal settlements (ironically enough deemed illegal by the government whose constitution guarantees adequate housing for everyone).

Even though apartheid policies have ended, its effects are still in place. The regime that displaced and structurally underdeveloped these groups has been ousted, but the displacement and structural underdevelopment remain.

I spoke last week about the economic effects of apartheid — guaranteeing a permanent and exploitable black labor force and guaranteeing economic security and profit for whites. As the famous strikes of the last few months have demonstrated, living wages are still not a reality within South Africa’s largest and most important industries: farming and mining.

Farmworkers’ wages are still far below the bare minimum they need to survive. Wages went up from R69/day to R/100 day after workers striked in January demanding R160. The crisis here is that after wages of roughly R105/worker/day, it becomes more cost efficient for farmers to use mechanized labor.

As we discussed with a facilitator at the Slave Lodge Museum, slavery has not disappeared; it has been replaced with wage labor and rent control.

Next, we turn to the United States.

Very simply put, nearly every local, state and federal office of law and “justice” is guilty of enacting or enabling everything from the rape of black women, to the forcible separation of families, to the legal murder of thousands of African Americans, to the structural underdevelopment of the race.

Most of these things may now be illegal, but that does not change the fact that the institutions that were designed to “serve and protect,” “defend the Constitution” and “educate” failed to do any of these things, were not punished or held accountable for such actions and continue to exist with the same fundamental structures that they had during slavery, during Jim Crow, during apartheid.

Accordingly, we cannot have any illusions that “democracy” or “justice” have ever existed in our contexts. We might have something like “democracy” or “almost justice,” but not the things themselves.

And we won’t have the “real deal” until we recognize and root out the inherent structural connection between racial oppression, class exploitation and the profit of the state and/or corporation.

The same racist capitalism and “democracy” that utilized coerced slave labor for profit and murdered indigenous Americans for land then underdeveloped black life for the purposes of low-cost wage labor. Following civil rights legislation and the globalization that we’re used to today, the racist logic of profit acquisition shifted south, west and east, to utilize the third world labor (which is necessarily black and brown) to serve the same ends. So we wind up with underemployment and structural unemployment of poor and working-class blacks (who are no longer needed by the system), the use of migrant groups and the global south for cheap labor.

Class oppression becomes tied up with racial oppression across most minority groups. Poor whites, who have historically resisted organization under unions out of refusal to work with black workers, also get the short end of the stick due to racism.

Slave labor has been replaced by (low) wage labor, and we can’t be blinded by the success of individual minorities — or by their recent inclusion in formerly exclusive structures — so long as this success is supported by the structural failure (or “almost success”) of other people.

At the root of this nation is genocide and slavery — a country founded on these inhumanities can never be just, be free, but we can strive to rectify these injustices.

As one of the panels at the Slave Lodge Museum concluded, “THEY FOUGHT FOR THEIR SURVIVAL AND INSPIRED OTHERS TO RESIST SLAVERY.”

We have to start and keep fighting for a better world, and that means an unwavering commitment to fighting and resisting class exploitation, racism and all other forms of oppression.