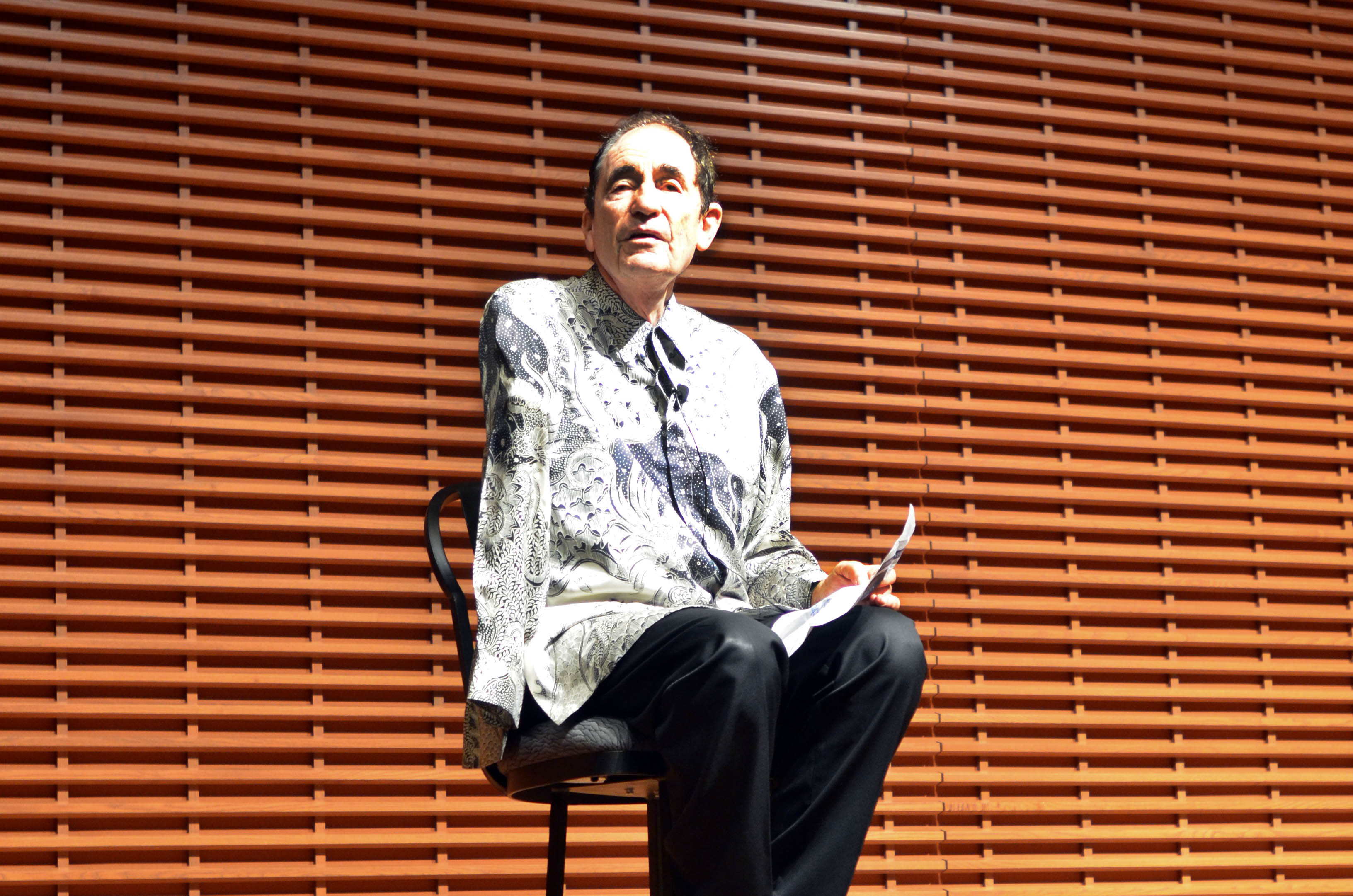

“[Nelson Mandela] became the leader because he was the best, not because he was the only,” reflected Albie Sachs, a renowned South African anti-apartheid activist and former judge, in a packed Cemex Auditorium on Wednesday evening. “He was somehow more articulate, more composed [and] more able to capture the sentiments of the people.”

Sachs, whose hour-long lecture largely served as a tribute to the ailing Mandela, was this year’s keynote speaker for Stanford’s Summer Human Rights Lecture Series, a feature of the Summer Human Rights Program that offers public lectures by eminent leaders of movements for equality. His legacy in South Africa includes working to draft the country’s post-apartheid constitution and serving on the nation’s Constitutional Court for 15 years, in which capacity he authored the court’s opinion legalizing same-sex marriage in South Africa.

Having been introduced by Freeman Spogli Institute Senior Fellow Helen Stacy, Sachs focused his speech on his personal experiences with Mandela, moving between anecdotes in recounting the fight for equality in South Africa. He singled out a pop concert at London’s Wembley Stadium in 1988, which took place on Mandela’s birthday and sought to rally support for his early release from prison, in contextualizing the mixed reactions to Mandela’s eventual release 15 months later.

“I had some anti-apartheid friends and their faces were long!” Sachs recalled. “They were full of indignation. We were full of joy…It’s a kind of virus that sneaks into many human rights movements, a virus that destroys the joy and the capacity to celebrate. You name and shame so much that you forget about laughter, fun, humor, dreams and poetry because everything is just focused on exposing the terrible things that are happening.”

Sachs attributed Mandela’s inspirational leader to his ability to be a “great follower” and a “great listener,” and stressed the significance of Mandela’s life to broader human society.

“He reconceived the notion of civilization,” Sachs said. “He did more in his person to destroy the myths of racial supremacy than all the textbooks [and] all the scientific studies could ever do.”

Turning to a more light-hearted component of Mandela’s unique personality, Sachs noted the former president’s distinctive style in both character and in dress. He underlined Mandela’s emphasis on egalitarian values and reluctance to be a monolithic leader of South African society, and recalled how Mandela chose to dress in relaxed, printed shirts instead of suits or other “formal things that make men look like penguins.”

“This wasn’t Mandela with his huge press corps and his speech writers and his image makers saying, ‘That will be a fantastic photo opportunity!’” Sachs said, highlighting an incident where Mandela walked nonchalantly into a shop to purchase dark shoes. “It was informal. He had a natural authority and presence. He didn’t have to force it.”

Sachs expressed his appreciation for Mandela’s political trailblazing and referenced his legacy’s persistence despite his deteriorating health.

“Just as in life he united the nation, so even in death he is uniting South Africans,” Sachs explained. “South Africa moved from being a [apartheid] state to being a constitutional democracy, and Mandela put his seal on that. In that sense, his life is embodied in the whole constitutional nature of our country…The things he was fighting for, the things he was willing to die for, remain entrenched in our family.”

Responding to audience questions in a post-lecture question and answer session, Sachs offered a candid insight into his time in solitary confinement in 1963.

“It was far worse than I had imagined. I thought that to be brave all you had to do is be brave,” Sachs said. “You’re fighting yourself. You’re fighting loneliness. On a really good day, I just felt despair. On a bad day, [I felt] deep, deep depression. And all the ideas about freedom and justice and liberation just went out after about two days.”

Sachs also described his personal experiences with acceptance and forgiveness, citing his relationship with a man who had attempted to assassinate him. The attempt, which took the form of a car bomb, resulted in the loss of Sachs’ right arm and his vision in one eye.

“[Henry] was on that side and I was on this side. In that sense, it wasn’t personal,” he elaborated.

After Henry attempted to make amends by speaking with Sachs, the two established a relationship characterized by camaraderie as opposed to hatred.

“We were beginning to love the same country. Instead of the person who tried to blow me up in some anonymous thing out there filled with hatred, now it was Henry,” he said. “If you are living with rancor, it’s trapping and holding you down. If you can find a way of getting past it, you will be getting stronger.”

As he neared the end of his lecture, Sachs decline to suggest any set path for audience members.

“I have no counsel or advice to offer whatsoever,” he concluded. “I hope you are as irreverent, creative and impulsive as we were when we were young. That you dream as much as we dreamed. That you want to change the whole world. For how to do it, you go find your own way, because we had to find our own way. That’s all that I can say and that’s all that I am going to say.”