It seems rather ironic that offenses good enough to march to the red zone so often sputter and die once they get there. Defenses go to their blitzes and bring the house. Running backs are confronted by piles of men where daylight once appeared. Quarterbacks run around but can’t find an open man. Much is made of red zone scoring percentage, but even without forcing turnovers, teams win championships by forcing field goals in the red zone. It’s the reason why head coach David Shaw specifically handles play calling in the red zone. Generally, inside the 20 is where games are won.

In Saturday’s win against then-No. 9 UCLA, Stanford’s stout defense held the Bruins to 10 points – nearly a fifth of UCLA’s scoring average on the season. The Bruins never got anything going on offense except for a 75-yard drive in the third quarter, which was capped off by a 3-yard touchdown pass to Shaq Evans to open the fourth quarter.

Defenses tighten up in the red zone because when they’re backed up against the wall, they don’t have to defend downfield anymore. Offenses can’t fully stretch the field with downfield passes, and with so little space, game-breaking speed becomes much less of a factor. That removes the need for safeties to protect the middle of the field – it’s as if the defense gets an extra player once it’s lined up at the goal line. Every defensive coordinator in America will dial up the blitz with this sort of advantage.

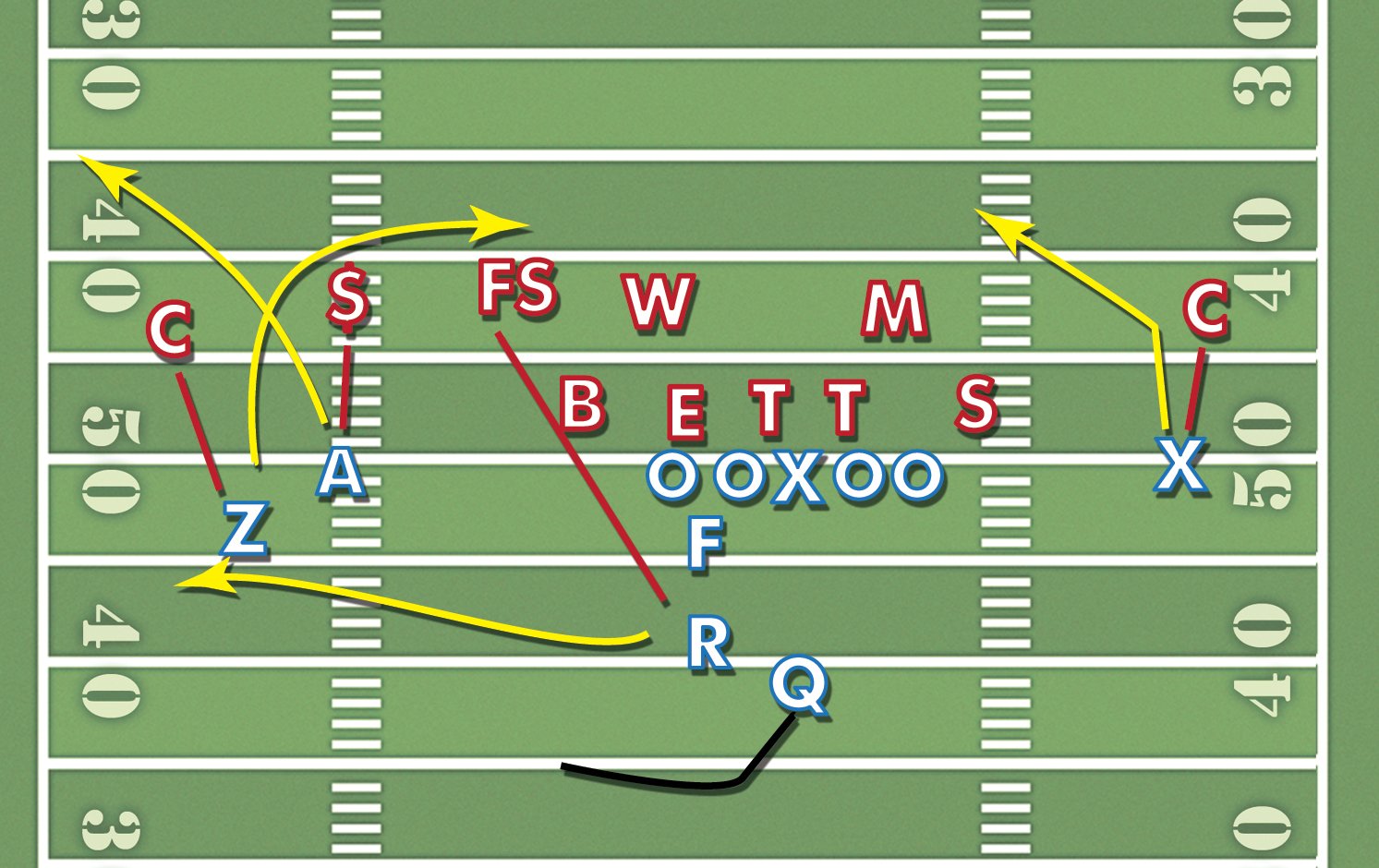

Stanford’s defense lined up in man coverage, each defender taking the UCLA player across from him. Free safety Ed Reynolds green-dogged UCLA running back Steven Manfro (R), blitzing if Manfro pass-blocked and covering Manfro if he tried to catch a pass. Since football is an 11-on-11 game and one offensive player has to carry the ball, Stanford could always bring one more blitzer than UCLA could handle.

As it was, UCLA’s dual-threat quarterback Brett Hundley had repeatedly burned Stanford on quarterback draws and scrambles, and Stanford opted to drop linebacker A.J. Tarpley (M) in a spy technique a few yards behind the line of scrimmage so that Hundley wouldn’t be able to escape. Nevertheless, with six pass rushers against six blockers, one mistake by UCLA and Hundley would be running for his life.

UCLA called a fairly common spacing concept to the left – receiver Devin Lucien (A) ran a fade to the corner, while Evans (Z) slanted to the inside. Manfro headed to the flat to threaten the defense. Hundley flowed to the play side, with a backside slant behind him to punish Stanford in case they didn’t spy a linebacker.

This combination is so popular because it is effective against both man and zone coverage. A and Z ran rub routes, A crossing over Z – a combination that defensive coaches both more derisively and more descriptively call “pick routes.” Manfro’s route drew away Ed Reynolds, opening up a large space in the middle of the field. Against man coverage, with Lucien effectively blocking strong safety Jordan Richards ($) with his body, Evans could break inside unimpeded and run free. Against zone coverage, Richards and Devon Carrington (C) would simply exchange coverage responsibilities and neutralize the rub routes, but with Reynolds in the middle of the field, there would be nobody to cover Manfro. Nevertheless, the play relied on Hundley having enough time to throw the ball.

Against Stanford’s man coverage, the routes unfolded perfectly. Stanford’s blitz nearly got to Hundley – not one but three players came close to sacking him – but Hundley hit the wide-open Evans for six. What Hundley later found out was that although the Bruins won that battle, Stanford’s pass rush would harass him all game, and that his pass would be the last points the Bruins would score that day. Stanford’s defense was ultimately triumphant, all but extinguishing the Bruins’ national title hopes.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.